Sea Venture

1609

On July 28, 1609, the SEA VENTURE drove itself intentionally onto a reef off the southeastern tip of Bermuda. This was an unfortunate development in the plan to bring relief to the dying colony of Jamestown. The shipwreck, and the drama that unfolded after it, were the source for Shakespeare’s “The Tempest”. One of these castaways helped build a ship, made it to Jamestown, eventually returned to England, and then sailed to America on the Mayflower. This was ancestor Stephen Hopkins, a sailor who has the unique spot in history of contributing to the founding of Bermuda, Jamestown, and Plymouth…but he was almost hung on Bermuda for mutiny (preferring a verdant island to expectations of starving in Virginia), was mutinous again off Cape Cod, and was repeatedly fined in Plymouth for drinking too much.

To Sea

Hopkins was born around 1582 in Hampshire during the reign (1558-1603) of Queen Elizabeth I. As England fought with other colonial powers on many fronts, Elizabeth’s successor, King James I, chartered the Virginia Company to colonize the East Coast of North America. The first trip put colonists ashore in Virginia on May 13, 1607. In 1608, Hopkins left his wife and three children (including Constance, baptized May 11, 1606) and joined the “Third Supply” fleet to Jamestown. He had no money to invest, nor any land or title, and does not, therefore, appear on the list of investors; he is among the sailors, soldiers, and servants on the fleet’s flagship, the SEA VENTURE. The investors (“adventurers”) included 21 peers, 96 knights, 53 captains, 28 esquires and an assortment of 400 other citizens; this included the Earl of Southampton, Shakespeare’s patron. Nine ships left Plymouth, England with 600 settlers under the command of admiral Sir George Somers, who had sailed with Sir Francis Drake and Sir Walter Raleigh. The master of the flagship, SEA VENTURE, was Captain Christopher Newport, who had been the Captain of the SUSAN CONSTANT which, along with GODSPEED and DISCOVERY were the first three ships to Jamestown in May 1607; Newport had also returned to Jamestown two more times on supply missions. A typical contract for someone in Hopkins’ position would be three years of indentured servitude in exchange for transport to the colony, food, lodging, and 10 shillings every three months for his family in England; after the indenture, the award was 30 acres in the colony.

The Wrecking

The SEA VENTURE, 300 tons, was among the first single-timbered ships with guns on the main deck; she was armed with eight nine-pounder demi-culverins, eight five-pounder sakers, four three-pounder falcons, and four arquebusses. SEA VENTURE left England June 2, 1609 and carried 150 passengers, including Sir Thomas Gates who was on his way, along with his secretary William Strachey, to become Governor of Virginia. Strachey described Hopkins as “a fellow who had much knowledge in the Scriptures, and could reason well therein” and was therefore chosen by the Chaplain, Richard Buck, “to be his clerke, to reade the Psalmes, and chapters upon Sondayes at assembly of the Congregation under him.” On July 23, 1609, Strachey recorded:

“On St. James Day, being Monday, the clouds gathering thick upon us and the wind singing and whistling most unusually, a dreadful storm and hideous began to blow from out of the northeast, which swelling and roaring as it were by fits, some hours with more violence than others, at length did beat all light from the heaven, which so like a hell of darkness turned black upon us. For four-and-twenty hours the storm in a restless tumult had blown so exceedingly as we cold not apprehend in our imaginations any possibility of greater violence; yet did we still find it not only more terrible but more constant, fury added to fury, one storm urging a second more outrageous than the former. It could not be said to rain, the waters like whole rivers did flood the air.”

The ships were separated in the hurricane; one was lost, and seven reached Jamestown. The SEA VENTURE sprung leaks in its relatively new planking, which the crew attempted to stop with pieces of beef. All hands took a turn at the pumps, including the Admiral and Governor. SEA VENTURE’s cargo of biscuits, when wet, clogged the pumps. All were “commending our sinful souls to God” when, on day four of the storm, which was receding, Somers, who was at the helm, sighted land. Somers purposely drove the SEA VENTURE over a reef less than a mile from Bermuda on July 29, 1609. Strachey wrote “The boatswain, sounding at the first, found it thirteen fathom, and when we stood in a little, in seven fathom; and presently, heaving his lead the third time, had ground at four fathom; and by this we had got her within a mile under the southeast point of the land, where we had somewhat smooth water. But having no hope to save her by coming to an anchor in the same, we were enforced to run her ashore as near the land as we could, which brought us within three quarters of a mile of shore.” Also aboard was Silvester Jourdain, who wrote “the ship kept from present sinking, when it pleased God to send her within half an English mile of that land that Sir George Somers had not long before descried, which were the island of the Bermudas. And there neigher did our ship sink but, more fortunately in so great a misfortune, fell in between two rocks, where she was fast lodged and locked for further budging; whereby we gained to only sufficient time, with the present help of our boat and skiff, safely to set and convey our men ashore (which were 150 in number) but afterwards had time and leisure to save some good part of our goods and provision, which the water had not spoiled, with all the tacking of the ship and much of the iron about her, which were necessaries not a little available for the building and furningshing of a new ship and pinnace.” All crew made it ashore in the boats, as did Hopkins, reportedly clutching a barrel of wine.

The ship was salvaged over the next few days, leaving only the ribs. They ate the berries and heads of palmetto trees, which were described as “farre better meate than any cabbage.” The crew found hogs, which Spanish sailors had previously introduced; the SEA VENTURE crew was certainly not the first to set foot on the island. In 1593, Henry May became the first recorded Englishman on the island, though not by choice: he was on a French ship that hit the reefs; Juan de Bermudez purportedly discovered the island in 1503, after whom it was named. The land was an unbroken forest of cedar and, having saved the carpenter’s tools, the crew built a small bark of 18 tons and, instead of pitch, made lime and mixed it with the oil of tortoises. They sailed away. Similarly, Somers had a boat built for fishing and exploring, and he also mapped the island, including an illustration of the SEA VENTURE’s dog chasing the wild hogs. The longboat from SEA VENTURE was fitted out to head to Virginia, but was lost. Gates and Somers, divisively, began work on two separate ships: the DELIVERANCE, at 80 tons, and PATIENCE, at 30 tons. The former had most of the salvage from SEA VENTURE, the latter had only a single iron bolt.

Hopkins on Bermuda

A group of rebellious settlers wanted to build a third ship on one of the other islands to take them back to England, but they ultimately gave up and resumed work on the other ships. Strachey wrote of “conspiracy” “mutinie” and “rebellion” and there were, in fact, executions. Those who were rebellious feared arriving in Jamestown in ships not capable of returning to England, and thus being forced into servitude under different terms than they had signed up for. Hopkins was among these. In January 1610, Strachey said that one Stephen Hopkins argued:

“. . . it was no breach of honesty, conscience, nor Religion to decline from the obedience of the Governor or refuse to goe any further led by his authority (except it so pleased themselves) since the authority ceased when the wracke was committed, and, with it, they were all then freed from the government of any man . . .[there] were two apparent reasons to stay them even in this place; first, abundance of God’s providence of all manner of good foode; next, some hope in reasonable time, when they might grow weary of the place, to build a small Barke, with the skill and help of the aforesaid Nicholas Bennit, whom they insinuated to them to be of the conspiracy, that so might get cleere from hence at their own pleasures . . . when in Virginia, the first would be assuredly wanting, and they might well feare to be detained in that Countrie by the authority of the Commander thereof, and their whole life to serve the turnes of the Adventurers with their travailes and labors.”

Hopkins was reported to Gates and, at Hopkins’ trial:

“. . . the Prisoner was brought forth in manacles, and both accused, and suffered to make at large, to every particular, his answere; which was onely full of sorrow and teares, pleading simplicity, and deniall. But he being onely found, at this time, both the, Captaine and the follower of this Mutinie, and generally held worthy to satisfie the punishment of his offence, with the sacrifice of his life, our Governour passed the sentence of a Maritiall Court upon him, such as belongs to Mutinie and Rebellion. But so penitent hee was, and made so much moane, alleadging the ruine of his Wife and Children in this his trespasse, as it wrought in the hearts of all the better sorts of the Company, who therefore with humble entreaties, and earnest supplications, went unto our Governor, whom they besought (as likewise did Captaine Newport, and my selfe) and never left him untill we had got his pardon.”

Thus escaping a hanging, Stephan Hopkins continued as the Minister’s Clerk.

Jamestown

While the ships were being built, the first baby was born on Bermuda to John Rolfe, who later had a rather famous second wife in Virginia, Pocahontas, daughter of Chief Powhatan. Some of the discontents were left behind on Bermuda while PATIENCE and DELIVERANCE sailed away on May 10, 1610 and reached Jamestown on May 23, 1610. Jamestown was a desolate sight after the relative bounty of Bermuda. Only 60 of the original Jamestown settlers were still alive, and were in “the starving time,” having already turned in some instances to cannibalism. Strachey said “the palisades torn down, the ports open, the gates off the hinges, and empty houses rent up and burnt, rather than the dwellers would step into the woods a stone’s cast off to fetch other firewood. The Indians killed as fast, if our men but stirred beyond the bounds of their blockhouse, as famine and pestilence did.” All of the former SEA VENTURE crew, plus the Jamestown settlers, decided that the 10-day supply of food was not enough, and prepared to sail up to Newfoundland, then back to England. While anchored at the mouth of the James, they were intercepted by an arriving boat that reported the imminent arrival of the fourth supply fleet with three shiploads of settlers and provisions. PATIENCE returned to Bermuda en route to England, where Somers died in November 1610. His son returned to England, and King James granted a charter to the Somers Island Company to colonize Bermuda.

Hopkins was not yet back in England when his wife died in 1613, so his unknown route home may have been circuitous and is not recorded in any of his writings; he may have remained in Jamestown, though documentation has not yet surfaced. It is believed that Hopkins returned to England between 1615 and 1617. While he was absent, the church liquidated Stephen and Mary’s estate, which included items related to shop and bar keeping, professions which Hopkins later undertook in Plymouth. Hopkins’ presence was recorded frequently by William Bradford in his dealings with the Indians; he was in the initial landing party in Provincetown “for counsel and advice” to Miles Standish and was able to recognize Indian traps; when Squanto arrived in Plymouth, he resided with the Hopkins family; the peace treaty on March 22, 1621 with Massasoit was signed in the Hopkins home. This leads support to the concept that he remained in Jamestown for some time and had extensive knowledge of Indian affairs. It is also likely that he was present at, and may have even helped officiate, the wedding of Pocahontas and John Rolfe in April 1614. The couple returned to England in 1616 and it’s also possible that Hopkins returned on the same ship.

Shakespeare

William Shakespeare had multiple connections to the Virginia Company and also to William Strachey who, on July 15, 1610, had written a long letter entitled “True Reportory of the Wrack, and Redemption of Sir Thomas Gates Knight.” The letter came back to London with Gates, although Strachey did not return until the Fall of 1611. Another of the first records of the events was written by Silvester Jourdain, from the same town as Somers, who was aboard the SEA VENTURE and published in London, in 1610, “A Discovery of the Barmudas.” Shakespeare’s, “The Tempest,” uses this work for seemingly countless aspects of construction, themes, details, plot, language, and wording. The first recorded performance of The Tempest was at Court on November 1, 1611. As on Bermuda, in the Tempest, two sets of conspirators question the authority of the lives of Alonso and Prospero. Strachey says that “so willing were the major part of the common sort, especially when they found such a plenty of victuals, to settle a foundation of ever inhabiting there.” Shakespeare has Stephano (i.e. Stephen Hopkins; character is “Stephano – a drunken butler”) and Trinculo plotting to stay and rule the island, with Stephano saying “we will inheret here” and, when encouraged to doing “that good mischief which may make this island Thine own forever,” Stephano responds “I do begin to have bloody thoughts.”

England

By late 1617, Hopkins and his motherless children lived in a home just outside the East wall of London, on the high road entering the city at Aldgate. Hopkins was a tanner and a leather maker at this time. Nearby was the Henage House, an apartment building in a converted mansion in which many nonconformists lived, including Mayflower passengers William Brewster, John Carver, and Robert Cushman; all of these were from the Scrooby separatist congregation who had left for Leyden, Holland but were back in England to raise money for a patent to create a settlement in North America. Thomas Weston, a merchant, helped form the adventure company (but did not have a King’s patent) to settle near the Hudson River and, to help the pilgrims overcome the risk of settlement, Weston enlisted settlers that were more economically-focused than religious, but who were sympathetic to the separatist cause. Hopkins, a neighbor of Weston, was among these “strangers” for his already valuable New World experience.

Mayflower

The MAYFLOWER set sail on September 6, 1620. The Hopkins family was one of the largest aboard the MAYFLOWER, and included his second wife, Elizabeth, children Constance, Giles, and Damaris, and two servants (Edward Doty and Edward Leister); Elizabeth also gave birth to a son on the voyage, named Oceanus. They sighted Cape Cod on November 9, 1620. The original goal was the Hudson River, which formed the northern border of the Virginia Colony, but the MAYFLOWER was not able to pass what is now know as Pollock Rip; she put it at Provincetown instead. Ironically, Hopkins had now, for the second time, arrived in an unintended place. And once again, the party became divisive, with some wanting to forge ahead to the Hudson, and others recognizing the onset of winter and the prudence of staying put. Hopkins, as he argued on Bermuda, argued that the terms of the adventure had changed and that they should remain in Massachusetts, but under new terms. William Bradford wrote:

“ye discontented & mutinous speeches that some of the Strangers amongst them had let fall from them in ye ship – That when they came a shore they would use their own libertie; for none had power to command them, the patente they had being for Virginia and not for New England which belonged to an other government, with which the ye Virginia Company had nothing to doe. And partly that shuch an acte by them done (this their condition considered) might be as firme as any patent, and in some respects more sure.”

The issue was settled by the captain, who would not risk the ship and anchored in what is now Provincetown Harbor on November 11, 1620. The 41 adult male passengers gathered together, guided by William Brewster, and wrote and signed the Mayflower Compact, which formed a “body politic” and established majority rule as the principle of government. On December 6, Hopkins was one of 10 men that braved the icy weather in the shallop and sailed Cape Cod Bay, exploring for a permanent home. The MAYFLOWER arrived in Plymouth harbor on December 16, 1620.

Plymouth

Of the first winter, Bradford wrote: “In two or three months time, half of their company died, especially in January and Febryary, being the depth of winter, and wanting houses and other comforts; being infected with the scurvy and other diseases which this long voyage had brought upon them, so as there died sometimes two or three of a day. Of 100 and odd persons, scarce 50 remains. And of these, in the time of most distress, there was by then six or seven sound persons who to their great commendations spared no pains night or day, but with abundance of toil and hazard to their own health, fetched them wood, made them fires, dressed them meat, made their beds, washed their loathsome clothes, clothed and unclothed them.” Hopkins was one of these helpers. The Hopkins household was one of only four to escape loss during the first deadly winter in Plymouth. He built and owned the first wharf in Plymouth Colony, and served in various government positions as might be expected among men in a small community. Hopkins had learned a great many survival skills on Bermuda and in Jamestown, and his fishing and hunting skills were very useful in Plymouth. He was active in and encouraged the fur trade, and expanded his house to include a store where the Indians could trade beaver skins for English goods. Supply ships began importing wine, beer, and spirits (brandy, gin) and in 1624 and Hopkins added a tavern.

However, as a “stranger” and not a separatist pilgrim, he was sometimes at odds with the community.

June 1636 – he was fined for battery of John Tisdale, whom he “dangerously wounded.”

October 2, 1637 – he was fined “for suffering men to drink in his house upon the Lord’s day…before & after the meetings, and for allowing servants & others to drink more than for ordinary refreshing.”

January 2, 1637/8 – he was “presented for suffering excessive drinking in his house” and for allowing one patron to “lay under a table vomiting in a beastly manner.”

June 5, 1638 – he was “presented for selling beer for 2d the quart, not worth 1d the quart” and for “selling wine, beer, strong waters, and nutmegs at excessive rates to the oppressing & impovishing of the colony.”

December 1639 – he was charged with “selling a looking glass for 16d when a similar glass could be bought in the Bay for 9d.”

While Hopkins was out of Plymouth on an Indian expedition in the summer of 1621, his servants committed Plymouth’s first criminal act. Doty and Leister began to compete for the affections of Hopkins’ daughter, Constance, who must have been rather good looking, as their argument took them into the woods where, with swords and daggers, they returned with wounds to hand and thigh. Bradford and Brewster consulted the legal books of Brewster, and the men had their necks tied to their feet for 24 hours in the town square. Hopkins plea reduced the sentence to an hour. Reflecting on Hopkins life, William Bradford wrote in the Spring of 1651:

“Mr. Hopkins and his wife are now both dead, but they lived above 20 years in this place, and had one sone and 4 doughters borne here. Ther sone became a seaman, and dyed at Barbadoes; one daughter dyed here, and 2 are maried, one of them hath 2 children; and one is yet to mary. So their increase which still survive are 5. But his sone Giles is married and hath 4 children. His doughter Costanta is also maried, and hath 12 children, all of them living, and one of them maried.”

Hopkins was the last non-separatist remaining at Plymouth when he died; to which Bradford said that Plymouth was left “like an ancient mother grown old and forsaken of her children.”

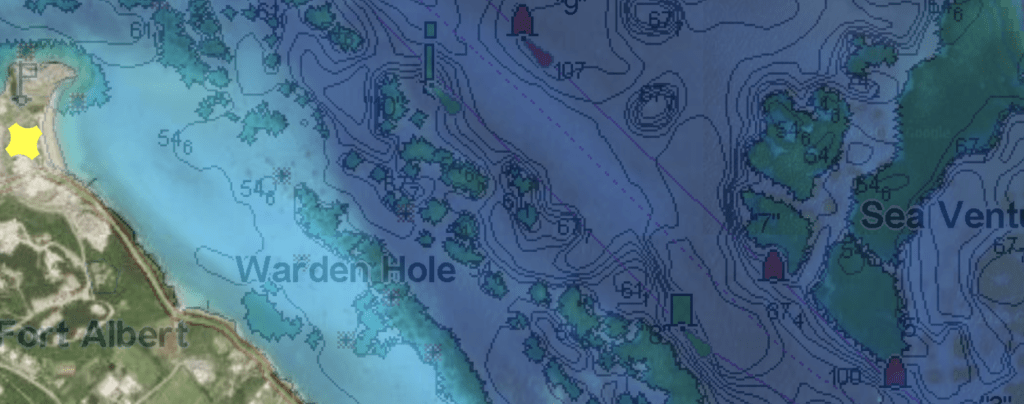

Sea Venture Today

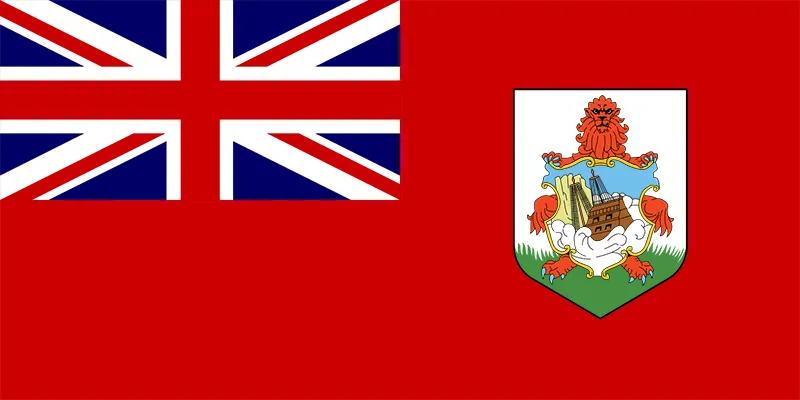

The Sea Venture was found in 1958 off the northeastern tip of Bermuda – St. George’s, Gates Bay – by an American diver, Edmund Downing. Years later, proper marine archeology began and recovered artifacts include Bellarmine jars, coins, candlesticks, a cannon, bar shot, 5,000 musket balls, cutlery, pipes, thimbles, buttons, coins, and jewelry. Merchant weights bearing the mark of King James put the date after 1603, and clay pipes recovered were not in use after 1610. A piece of English pottery that matched another in Virginia was the final conclusive piece of evidence. The ships timbers are still under water and, fortunately, diving on the wreck site is prohibited.

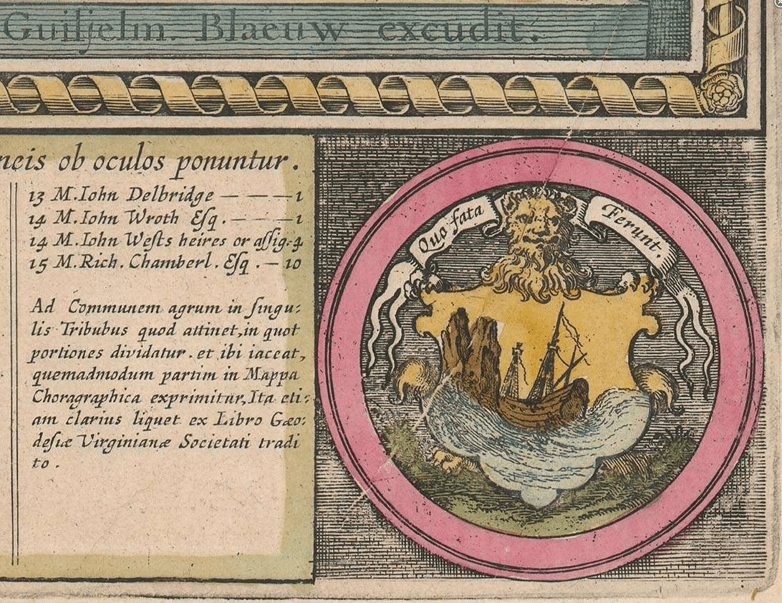

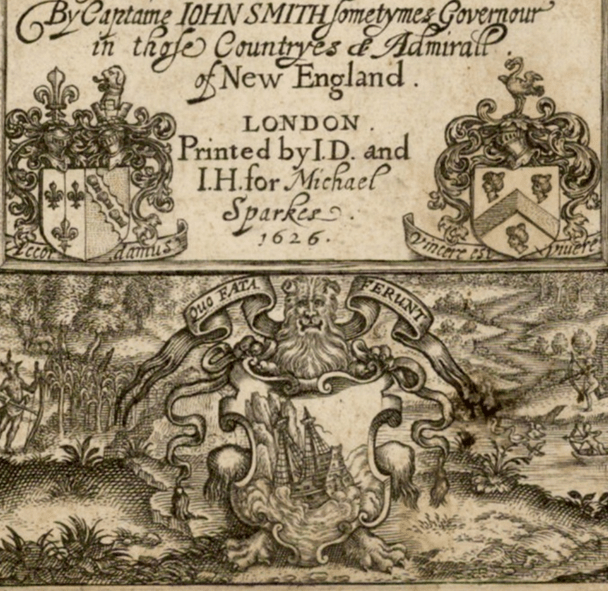

The Sea Venture also lives on in the coat of arms on Bermuda’s official flag. Analysis of the wrecked timbers has allowed marine archeologists and naval architects to reproduce the lines of a ship that looks very similar to that shown by John Smith (1626) and Willem Blaeu (1640). Creative license was taken by both of these artists, with different levels of gun ports, stern structure and mast configuration. More significantly, however, creative license was taken with the wrecking itself and, specifically, the rocks & cliffs, and 20 foot waves that would have been broken by outer reefs by the time they reached the SEA VENTURE’s resting spot. The coral flats that SEA VENTURE drove up on were in relatively shallow water, as shown in the contemporary chart below. The surviving accounts of the wreck, as noted above, seemed almost a relief after the harrowing days and nights of the hurricane. To the non-mariner artist, a simple grounding shipwreck wouldn’t seem like “a shipwreck” nor would it present well in a dramatic and inspirational coat of arms. Thus, the Somers Isles Company, Smith, and Blaeu all took dramatic license in their designs. These rocky cliffs exist in many places on the island, albeit inaccessible to an inbound ship like SEA VENTURE, and not where the SEA VENTURE went aground. There were earlier shipwrecks, including that of French ship, BARBOTIERE, in 1593 with an Englishman aboard, Henry May, that occurred out where cliff-like rocks could have existed at the time. But the purpose of a coat of arms is to memorialize something significant and ongoing. The wrecking of the SEA VENTURE began the process of Bermuda’s inhabitation as survivors stayed behind and did not sail to to Jamestown. More significantly, Sir George Somers, whose hand was literally and figuratively on the tiller of the SEA VENTURE, returned to the island – and died there – on the way back from Jamestown to England to begin Bermuda’s permanent settlement. These are the events that sprung from the SEA VENTURE and are being memorialized. It does not seem logical that the Somers Isles Company would honor a random Englishman, not part of the Company, sailing on a French ship. Seen another way, the image in the coat of arms could be a foreshortened view of SEA VENTURE on its shoal, with the bluffs of the northeast tip of St. George’s in the background, high upon which Fort Saint Catherine sits today, perched well above the beach at Gates Bay where the survivors came ashore. It would be hard to fit much more of an illustration in a one-inch crest.