Richard Smith

1596-1666

At the rather late age of 42, Richard Smith left England with his family for the economic opportunities afforded by the colonies, and for religious reasons, seemingly in that order. His time here was anything but settled, residing in Plymouth Colony, Rhode Island, Long Island and Manhattan – all while maintaining a trading post in the middle of the Narragansett territory, personally sailing his goods around the Northeast, and maintaining a wide social and commercial network.

England

England

Richard was born around 1596 in Thornbury, Gloucestershire, England. His name was spelled “Smyth” in England, but generally with an “i” in New England. In 1616, Gloucester was a target of bishop William Laud, whose persecution of Puritans under King James was intense. Together, they burned puritan Edward Wightman at the stake in 1612, the last person to die this way in England (some years later, Edward’s grandson actually married Richard’s granddaughter in Rhode Island). Richard came with his wife, Joan Barton, and their children, all of whom were born in England: Richard Jr., Joan, Katharine, Elisabeth, and James.

Richard was not someone to sit still. There are conflicting historical writings about his movements upon arriving in New England. However, he was so active and engaged in his communities that he appears with great frequency in the records. By sorting these records chronologically, his story unfolds.

New England

He first appears as having taken the oath of allegiance and fidelity in Taunton, Massachusetts – or Cohannet – in 1638, along with an immediate listing of a John Smith who presumably is a relation, possibly a brother. Taunton, in Plymouth Colony, is exactly halfway between Plymouth and Providence, where the Taunton River flows into Mount Hope Bay to the north of Aquidneck Island, just 30 miles away. A later petition to the King dated July 29, 1679 stated that “Richard Smith, deceased…came into New England, began the first settlement of the Narrangansett Country (then liveing at Taunton in the Colony of New Plymouth), and erected a trading house on the same tract of land…”

Richard did not remain in Taunton long. Both Richard and John are listed amongst the inhabitants admitted on Aquidneck Island at the town of Newport as of May 20, 1638 (original), which was only two months after the Aquidneck compact was signed on March 7, 1638, and a full year before Newport was founded as a distinct town. Richard gravitated to the northern end of Aquidneck Island, where he was admitted to Portsmouth in July 1640 and granted a lot on August 8, 1640. It is during this time that he likely met Roger Williams and established a friendship based on their religious views, mutual interest in the Indians, and trading. Years later, Richard’s son wrote that the Indians “being well satisfied in his [Richard Sr.] comeing thither, that they might be supplyed with such necessaries as affore times they wanted, and that at their own homes, without much travel for the same. The said Richard Smith likewise being so well pleased in his new settlement in a double respect; first, that hee might bee instrumentall under God in propagating the gospel among the natives, who knew not God as they aught to know him, and took great paines therein to his dying day.”

New Amsterdam

In New Amsterdam, which only had a population of around 300 at this time, Richard met Gysbert Opdyck, who married Richard’s oldest daughter, Katharine, in 1643 on Manhattan. In September 1643, Director-General Kieft brought together all the citizens to elect eight men to consult with the Director and his Council. The Eight Men were required to attend meetings with the Director and Council every Saturday, and five of the eight were required to adopt legislative actions. In the last year before Kieft’s recall and 1646 replacement with Peter Stuyvesant, both Richard and Gysbert were part of the second group of the “Eight Men” council appointed in 1645 to deal with the Indian issues, including the signing of a treaty. The other six included Francis Doughty, Jacob Stoffelsen, John Underhill, George Baxter, Jan Evertsen Bout, and Oloff Stevensen van Cortlandt. The treaty was signed on August 30, 1645 in the presence of the entire New Amsterdam community and several Sachems.

Richard acquired land on July 4, 1645 on Hoogh (High) Street. This land was what is now 65 Stone Street, 87-89 Pearl Street, and 91-95 Pearl St. This block is just west of Hanover Square, and Richard built a house and storehouse there. At this point in time, Pearl St. was the waterfront of the island of Manhattan. Stone St. was so named because it was the first street in New Amsterdam to be paved with stone. A detailed analysis of Richard’s land is on the New Netherland page here. In the 1660 map, the primary Smith dwelling was the house in the upper (Western) portion of the lot on Stone St., while the smaller building in the middle was a warehouse. The larger building on Pearl St. was built after Smith’s ownership.

PATENT TO RITCHERT SMIDT We, Willem Kieft, etc… have given and granted to Ritchert Smidt a lot located on the island of Manhattan on the East River west of the lot of Tomas Willet; it extends next to the aforesaid lot of Tomas Willet or on the east end 5 rods; in length along the bank on the south 11 rods, one foot and 7 inches; its breadth on the east side is 4 rods 7 feet; on the north side along the wagon road 12 rods and 4 feet; amounting in all to 62 rods, 7 inches, with the express conditions etc… Done in Fort Amsterdam, 4 July 1645. (original)

Trading

Sloop Bay shows up (at least phonetically) on some of the oldest maps of the region, beginning with Adriaen Block’s 1614 map as “Sloupbay.” He was the first to denote Manhattan as an island and sail down Long Island Sound – and named an island for himself. It shows again in Blaeu’s 1635 map as “Chaloep Bay,” and in Jansson’s 1657 map as “Sloep Baye.” It’s clear from these maps that this is what is now called the west passage of Narragansett Bay – including both Cocumcussoc and Dutch Island.

These depictions of the land and water from Manhattan to Cocumcussoc are both amazing in their detail and lack thereof. Dutch – or “Quetenis Eylant” – does not show up until the last map, but too far out to sea. Of particular note are the many “Archipelago” designations along the sound. In those days (as now, even with motors), it would have been extremely hard to navigate the islands, rocks and currents between Smith’s two trading operations without some more detailed charts, or a very good memory.

Beaver pelts and wampum are key currencies that show up in the records, and Richard even entered into real estate transactions in beaver pelts. The initial trading activity involved gathering pelts and other goods such as corn, wheat and livestock to exchange for European goods such as kettles, silverware, thimbles, rings, fishhooks, buckles, axes, knives, chisels, locks, scissors, shovels, and guns. Smith’s trading post dealt in liquor, but Roger Williams refused – and he ultimately shut down all liquor trade with the Indians. In a letter from Roger Williams written in Providence on August 19, 1669 to John Winthrop, he wrote:

“While you were at Mr. Smith’s that bloody liquor trade (which Richard Smith hath of old driven) fired the country about your lodging. The Indians would have more liquor, and it came to blows. The Indians complained to Richard Smith [Jr]. He told them he was busy about your departure. Next day the English complaind of some hurt and went with twenty-eight horse (and more men) to fetch in the Sachem. The Indians with a shout routed these horses, and caused their return, and are more insolent by this repulse; yet they are willing to be peaceable, were it not for that devil of liquor. I might have gained thousands (as much as any) by that trade, but God hath graciously given me rather to choose a dry morsel, etc.”

On January 26, 1669, Richard Jr. wrote to John Winthrop, the awful story that “about one wecke since one indyan with two Squose gott into a mans howse here in Narragansett in the euining, the man that night bot being att home, and drewe and draink so much Rumb out of his caske that they were so drunke that gooeing homards they laye downe in the cart waye and were frozen all ded by the morning.” While most of Richard Sr.’s trading was coastal and European, the New England and New Amsterdam networks were already beginning to supply the Caribbean. Another merchant trader, Isaac Allerton of the MAYFLOWER, kept a waterfront warehouse very near Richard’s on Manhattan. On August 25, 1647, William Aspinwall in Boston recorded a transaction for Raph Woory of Charlestown involving two ships “now rideing at Anchor in Charls river nigh unto Boston in the Massachusetts Bay” to ship cattle and other goods to Barbados. This was the GROOTE GARRIT under Capt. Jelmer Thomson and the BEVER under Capt. John Clawson Smale. Payment was to be made

“unto the honorable Peter Steveusant, Governor generall of the New Netherlands by Mr. Isaac Allerton uppon Certificate of the Arrivall & delivery of the said freight at Barbados & for the other hundred pounds sterling to be payd by Assigment upon Mr. Rich. Smith either in Bever, according to the Covenant between Mr. Woory & the said Smith, or in the same comodities at the same price did the said Mr. Smith by the said Mr. Woory…In consideration whereof the said Jelmer & John do covenant & agree to Delivr or cause to be delivered such Cattle and goods as the said. Ra. Woory shall shipp aboard the above said ships, upon the said Island of Barbados, the danger of the seas expected…It is likewise agreed that in case either of the said ships should miscarry in theire said voyage, then the other to receive the payment remaining ratum pro rato, to with, for the Greate Garrett 240 sterling & the Bever 180 sterling for the whole.”

In a later New Amsterdam record, on July 18, 1648, Richard posted a bond for Isaac Allerton for “the freight of the yacht GROOTE GERRIT to Barbados.” As discussed below, this Caribbean trade would mark a critical turning point for the Narragansett trading post, Rhode Island itself, and the colonies as a whole.

Back to Rhode Island

One of Richard’s last records in New Amsterdam regards the marriage of his daughter, Joan, in the spring of 1648. Richard refused to consent to Joan’s marriage to widower Thomas Newton of Fairfield, Connecticut, who had arrived there in 1639. Undeterred, the couple was married by a civil officer who “provided them instantaneously in his house with bed and room to consummate the marriage.” Richard took them to court and, with the backing of the government, fines were issued. (original) Yet by April 16, 1648, everyone was reconciled, although Richard was probably still furious. Richard and his family likely left New Amsterdam shortly thereafter to re-establish their home back in Rhode Island. The later King’s petition of July 29, 1679 recalls “he chose at last this place of Narragansett for his only abode; no English liveing neerer to him than Pawtuxet, at his first settleing, being beare twnety miles from him. That place now called Warwick, was not then thought on….afterwards Mr. Roger Williams, of Providence, likewise came to Narraganset and built a house for trade, near unto the former house of Richard Smith, who in some short time quitted his settlement and sold it to [his son] the said Richard Smith, who lived there alone for many yeares, his house being the resting place and rendezvous for all travellers passing that way, which was of great benefit to and use to the country…”

In 1651, Richard (senior) purchased Roger William’s trading house, thereby consolidating the Cocumcussoc operation. It was also known as “Smith’s Castle” because of the fortified stone construction of the primary building. It seems probable that the family lived at Cocumcussoc and kept the Portsmouth lands as investment properties, leasing them out as he did in New Amsterdam, or at least stayed in Portsmouth only part of the time. It was not difficult to travel to Portsmouth, and he shows up in the Portsmouth records on October 16, 1649 being named on the Grand Jury for the next General Court. Then again at a Portsmouth town meeting on April 29, 1650, he is chosen again as a Jury man for the General Court and also for the General Assembly in Newport in May. He was arguing in Portsmouth court over the maintenance of a fence with Francis Brayton, on land formerly agreed upon between Smith and William Brenton and Samuel Wilbore, on April 5, 1659 and again on May 7, 1660. This same Samuel Wilbore appeared in the Portsmouth records on November 8, 1648, with Richard as witness, “This Indenture Witnesseth that I Samuell Wilbore of Taunton have Barguaned & sould unto John Sandford of Road Island his heirs or assigns one piece of Meddo land”, which follows Richard’s link from Taunton to Portsmouth. Furthermore, Samuel Wilbore is one of the Pettaquamscutt purchasers, and is named in the royal charter of 1663 (after Richard Sr. had died), highlighting the subsequent link to Narragansett. Cocumcussoc underwent a significant transformation upon the return of Richard Sr. and his family. From a simple trading post in various goods, it evolved into its own productive source. Livestock herds increased, agriculture and dairy expanded, and Joan began making cheese from an old Cheshire recipe.

Richard continued to travel to Manhattan at least through 1659. In a City Hall record dated Friday, March 28, 1659, Smith’s agent, Evert Duyckingh, who lived on the same block, was offering the vacant garden portion for sale – “Mr. Smitt himself has valued it at fl. 500 in Beavers; he expects him here shortly.” Richard sold all of his New Amsterdam properties by 1662, just two years before Joan died in 1664, the same year the Dutch surrendered New Amsterdam to the English. Richard was also still purchasing land a few years before his death. On July 25, 1659, at Cocumcussoc, “Quisaquance Cheif Sachim of the Nankygansett, have sold…two-Island of Quononoqutt and Aquednessett..unto mr William Brenton mr William Coddington mr Benedict Arnold mr Richard Smith senr and Caleb Carr…for…sixty pounds…Wit. Thomas Green, The Marke of Quisaquance, Awashouse, Saukequaskne, William Eaton.” Quononoqutt is present day Jamestown, or Conanicut Island. Aquednessett is present day Quidnessett, which was only an “island” insofar as the creeks that dissect it. Richard junior is seen selling lands on January 20, 1687, giving English names: “have sold land in the Island Quononaqut Als: James Towne…three hundred and Seventy acres…and…their Portion in a small Island near…Island of Quononaqut called….Dutch Island and Purchased of the Indian Sachems with the Island of Quononaqut.”

Death

Richard Sr. died in 1666 at the age of 70 and is buried at Cocumcussoc, where he was marked by a simple field stone. Looking back on his life, Roger Williams wrote from Narragansett on July 21, 1679:

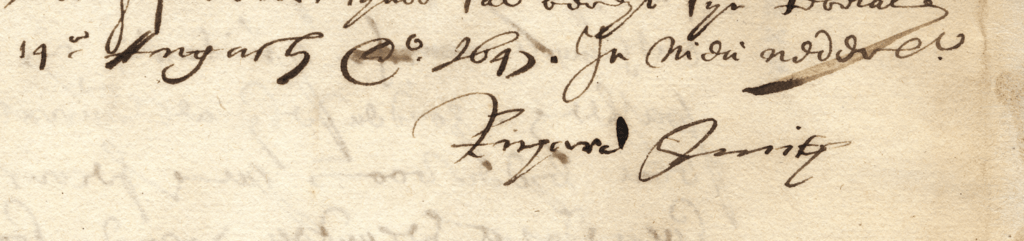

“I, Roger Williams, of Providence, in the Narragansett Bay, in New England, being (by God’s mercy) the first beginner of the mother town of Providence, and of the colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, being now near to fourscore years of age, yet (by God’s mercy) of sound understanding and memory; do humbly and faithfully declare, that Mr. Richard Smith, senior, who for his conscience to God left fair possessions in Gloucestershire, and adventured, with his relations and estate, to New-England, and was a most acceptable inhabitant, and a prime leading man in Taunton and Plymouth colony; for his conscience sake, many differences arising, he left Taunton and came to the Narragansett country, where, (by God’s mercy and the favor of the Narragansett Sachems) he broke the ice at his great charge and hazard, and put up in the thickets of the barbarians, the first English house amongst, them. 2. I humbly testify, that about forty years from this date, he kept possession, coming and going himself, children and servants, and he had quiet possession of his housing, lands and meadow; and there, in his own house, with much serenity of foul and comfort, he yielded up his spirit to God, (the Father of spirits) in peace.” (original)

War at Cocumscussoc

Despite the efforts of Roger Williams to broker peace in the region, the colonial desire for land and power led to conflict, as it had already done previously in New Amsterdam and Mystic. Within the wider King Philip’s War, what became known as the Great Swamp Fight occurred in December 1675. Cocumcussoc was used as the base of attack by the colonial force against the Narragansett tribe, and forty soldiers who died – including Smith family members – are buried on the property. In the Spring of 1676, retaliatory attacks began, including a burning of Cocumcussoc and also Providence, including Roger Williams’ house. Not only had Cocumcussoc lost all its livestock and stores supporting troops before and after the Great Swamp Fight, the original blockhouse dwelling was lost. In the same July 21, 1679 testimony given by Roger Williams above, about Richard Jr. he said:

“hath kept possession, (with much acceptance with English and pagans) of his father’s housing, lands and meadows, with great improvement also by his great cost and industry. And in the late bloody Pagan war, I knowingly testify and declare, that it please the Most High to make use of himself in person, his housing, goods, corn, provisions and cattle, for a garrison and supply for the whole army of New England, inder the command of the ever to be honored General Winslow, for the service of his Majesty’s honor and country of New England. I also humbly declare, that the said Captain Richard Smith, junior, ought, by all the rules of equity, justice and gratitude, (to his honored father and himself) to be fairly treated with, considered, recruited, honered, and, by his Majesty’s authority, confirmed and established in a peaceful possession of his father’s and his own posessions in this pagan wilderness, and Narragansett country.”

Cocumcussoc was rebuilt around 1678, in part using some of the materials of the trading post. It seems probable that Richard Jr., at that point a widower, lived with extended family at Quidnessett or even possibly Newport.

Cocumscussoc Legacy

Richard Jr. took over in 1666 upon his father’s death and ran the property until his own death 1692. Although married, he was childless, and Cocumcussoc passed to Lodowick Updike (1646-1736), who established and named Wickford as a new town. Lodowick was the son of Katharine Smith and Gysbert OpDyck, and his wife was Abigail Newton, daughter of Joan Smith (Richard & Katharine’s daughter) and Thomas Newton. Thus, Lodowick and Abigail were first cousins, both grandchildren of Richard Sr. There is a longer story about the subsequent history of Cocumcussoc, but our relevant family members stop with Gysbert and Katharine’s daughter, Elisabeth, who married George Wightman.

While George & Elisabeth were peers of Lodowick & Abigail, they did not reside at Cocumcussoc. George was born in London and his older brother, Valentine (1627-1700), moved first to Rhode Island, where he appears in the early Providence records. Valentine was fluent in Algonquin and was well known to Roger Williams, Richard Smith, and John Winthrop. Undoubtedly, Valentine is the reason George came to Rhode Island. They were both devout Baptists. Valentine sold George his primary holding, which he called “Aquidnesset” in his will, but is more commonly called Quidnessett, a 100 acre plot north or Cocumcussoc that had Narragansett Bay frontage. Over time, George brought his landholdings to 2,000 acres. His will, probated February 2, 1722, is extremely detailed – in which he delineated “In the hall:”, “In the lean-to:”, “In the lean-to chamber:” “In the hall chamber:”, “In the garret:”, “In the cellar:” etc. Which indicates that the land was farmed and, while he owned no slaves, it is likely that any farming output ended up in the Cocumcussoc trading system.

By the time Richard Sr. passed Cocumcussoc to Richard Jr., it had become a “plantation” in the colonial sense of a large social and agricultural enterprise, and likely the most longstanding in New England having been established in 1637/8, pre-dating Silvestor Manor on Shelter Island in the early 1650’s. Similar to London merchants and the pilgrims themselves when referring to “Plymouth Plantation,” it had nothing to do with slavery in the modern sense. Cocumcussoc was the first “plantation” in Narragansett, and contributed to the formal name of the state until 2020: State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations – with “Rhode Island” referring to Aquidneck Island.

Richard Jr. was as active as his father, and was similarly known to Roger Williams, John Winthrop Jr. of Connecticut, the Silvesters of Barbados and Shelter Island, and important sachems. More specifically to Cocumcussoc, its goods were being sold longer-distances:

Richard Smith Jr. to John Winthrop, Jr.

“N: London this second daye of maye 1670. Many uesalls are latly ariued from Barbados into Boston & one to Rode Island.”

Richard Smith Jr. to John Winthrop, Jr.

“Narragansett this 4th of Septemb 1671. My ocacions hath bin much to fit out our ship for Barbados, which nowe is redy within 3 or 4 days.”

Richard Smith Jr. to John Winthrop, Jr.

“Wickford in Naragansett this 24th daye of maye 1673. Here arrived a kaitch 4 days since att Newportt from Barbados; shee was chased 48 ours by a shipe about 100 leges from hence. Its judged sum sculking men of ware may anoye this cost…My respets & servis to Captt Silvestr his wivfe & family. RS.”

Richard Smith Jr. to John Winthrop, Jr.

“Wickford 15th Aprell 1675. For his Much Hounored frend Major John Winthrope Esqur att Newe London prsent.... Major Winthrop: Having this opertunity could doe noe lese butt saleutt you with the remembrance of my servis & returne of thainkfull acknowlidgments for all your love & favor. I had thought to have putt in att N to have given you the trouball of a visit, butt was crosed by reson of a fayer wind. Ouer uesall being full of lumbar we went derectt for Rhode Island; it we had sume good fraight one bord, namly Mistris Sylvster & her daufter Mistrs Grisell, & negro Symoney to atend them, whome we safly landed att Rhode island. When att Shellter island, by sume discoursce I herd, I perceved your company theare hath bin longe expected, and your abstance as much admired, for what causce I inquyred nott; it this I knowe, its safer exposcing your selvfe to travell on drye land then over such water gapes as those, where the tyde runs so swift. I should be verey joyfull to see you att my howse, wheere noe gentellman should be more welcome, & if you then had a mind for devercion sake to gooe ouer to Rhode Jsland I will waight upon you. Sir, here is noe newes, only I had the hapynes to receve a leter from Major Pallmes, who goott Safe to Barbados…..

Richard Smith Jr. to John Winthrop, Jr.

“Wickford 3d of novmb 1675. In Barbados hath bin a dredfull harycan, the like neuer knowne.”

Peleg Sanford to cousin Elisha Hutchinson

“Janry 6: 1667..we have been informed tht John Grafton is arrived [from Barbados]; which is Soe: then my Earnest Request unto yor Self is tht if he hath any musovad Sugr or Cotton wooll on Board for me that you will Receve & make Sayle thereof…and if he hath any othr goods for me please to Sent it up p mr Smiths sloope or any other Vessell th Bound hether.”

Peleg Withington to Weston Clarke & John Greene

“Barbados…Peleg Withington of the Island of Barbados..resident in the Towne and Parrish of St. Michalls doe make my friends Weston Clarke Secretary & Jno Greene merct, both of Newport, my True and Lawfull Attorneys…dated in Barbados the 24th Day of February…1686…before mee Richard Smith.”

While trading with the Caribbean was nothing new, as discussed in the case of Richard Sr., the scale increased in terms of supplies and goods sent south to Caribbean plantations – lumber, cattle, horses, provisions, European goods. The shipping book of Walter Newbury illustrates the breadth of goods – peas, wheat, butter, cheese, onions, cider, wool, oil, and lumber. An illustrative entry:

“Shipped by Walter Newbury, on PORTSMOUTH, Henry Beer, master, Newport to Barbados, unto Joseph Grove, Dec. 25, 1686…ten thousand five hundred of white oake barrll Staves with Heading, twenty barll train oyle, thirty four halfe barrll beefe, three firkins of hogs lard, three halfe barrl Cranbury, fiveteen Cask of tarr, one thousand two hundred Shingles, five horses with fourteen water Cask, a hunderd & halfe of Hoops…Eight boxes of Candles…acct & risque of Joseph Groves.”

Peleg Sanford, above, who lived in Barbados in 1663-4 and whose Hutchinson family remained there, imported sugar, molasses, rum and cotton from Barbados and dry goods and hardware from England, all of which he sold in Newport. With the proceeds thereof, he would purchase horses and provisions and ship them to Barbados. Other goods that returned from the Caribbean included flour, rice, salt, and fabrics. The most important returned good was molasses, which is distilled to make rum. Rum became an extremely important commodity for New England, especially Rhode Island, both for domestic consumption and as a key currency for exchange on the African coast. With the introduction of sugarcane as a crop, rum was being distilled in Barbados by the mid 1640’s and in quantity in Rhode Island by 1684. In 1702, it is estimated that 10,292 gallons were exported from Rhode Island to Africa and, through 1807, this totaled 10,980,724 gallons. This wasn’t mellow rum aged in wooden casks. Rather, it was freshly distilled overproof white rum for the “Guinea trade” on the coast of Africa. New England rum was therefore the first leg of the triangle, where it was sailed to the African coast in exchange for slaves, who were sailed to the Caribbean on the second leg, where they were sold and exchanged for goods to return to the northern colonies, including molasses to distill into rum and begin the cycle again. A similar triangle ran from Europe. Ships on the first leg also brought goods from New England to the Caribbean, and slaves to New England. Richard Jr. ultimately owned eight, which increased under the later Updike’s, who freed all slaves after the Revolution. It is with this turn of events beginning with Richard Jr. that “plantation” takes on the modern understanding. Rhode Island itself did not enter the slave trade through a direct voyage to Africa until 1709. While there is no record in the extensive Rhode Island archives of Cocumcussoc sponsoring any slaving voyages to Africa, all of New England and Europe were complicit in the trade by supporting the Caribbean economy. Lodowick Updike & Abigail Newton’s son, Daniel (1694-1757), who inherited Cocumcussoc after Richard Jr., spent time in Barbados as part of his merchant trading education – and there was possibly an English family connection to the Newton plantations on Barbados, which were established in 1654.

Enslaved in Algiers

The odious institution of slavery was not limited to the more widely known sub-Saharan African form. Gysbert & Katharine’s son, Daniel (brother to ancestor Elizabeth), sailed aboard the ship UNITY from Boston to London in late 1679. As it neared the British islands, it was captured on January 24, 1680 by an Algerian pirate vessel. All aboard the UNITY were taken to Algiers in February 1680 and sold into slavery. The so-called Barbary pirates sailed out of the primary northern ports along the Mediterranean and Atlantic coast for centuries and raided as far as Northern Europe, ultimately enslaving more than 1,000,000 people to work as servants and laborers. Ironically, Richard Smith Jr wrote to John Winthrop in Connecticut years earlier, on May 2, 1670, that “the Turke hath taken seuerall of our merchants ships in straits; one Mr Clements that went out from Boston they toke, & its noysd as if Mr Robert Gibes is taken by them, he went out of Virginia to gooe to Tangere.”

Some captives were held specifically for potential ransom, which was the case for at least two on the UNITY – Daniel, and his shipmate William Harris, another Rhode Island resident and peer of Roger Williams. Harris was able to send a letter home from Algeria on April 6, 1680, reaching Rhode Island on October 13, 1680:

“I pray to mind my danger and they they both stir up the Gentlemen that Imployed mee that they doe not leave mee in ArJeere…but since I came I saw Daniel Updike and he saith he had a plague sore, and that the sd sikness is here every sumer and begins in may, and that the last sumer here dyed nine of tenn of the English Captives but some say not soe many, speake to Mr Smith to Redeeme him and tell Lawdowick his Brotheer, Mr Smith, Mr Brindley and others with my harty tender Constant Care and Love…”

Hearing of Daniel’s situation – certainly with a sense of relief, joy, and fear – Richard Jr. sent a ship to Algiers with Daniel’s ransom – over 1,000 flintlocks for gunsmithing. It is believed that, upon his release, Daniel traveled to London with William Harris. From there, he returned briefly to Cocomcussoc to pay his thanks, then returned to London where he died in 1704 at the age of 44.