James Gandsey, Piper

1767-1857

The Beginning

James Gandsey was born in 1767. His father, in the family and popular history, was a British soldier stationed at Ross Castle, south of Killarney in County Kerry, Ireland. Here, he met James’ mother, who subsequently followed this soldier (as was common – if married – in a support capacity as sutler/laundress/nurse) on his regiment’s transfer to Gibraltar, leaving James behind to be cared for by her parents.

The Irish Establishment of the British army began in 1747 and continued through the French & Indian War and the American Revolution. Regiments were periodically rotated through barracks in different towns across Ireland. On the shore of lower Lough Leane, outside the town of Killarney in County Kerry, stands Ross Castle on a 150-acre island, which was used as a barracks until the early 1800s. In The Quarter of the Army in Ireland in 1752, the First Regiment of Foot, Royal Scots, commanded by Lt. General James St. Clair, Colonel, has three companies in the First Battalion stationed at “Rosscastle” and lists the names of the Captain, Lieutenant, and Ensign for each. According to Historical Records of the British Army – Historical Record of the First, or Royal Regiment of Foot, the movements of the Second Battalion disqualify it as that of James’ father. However, the First Battalion was stationed in Ireland in 1749 through 1768, with a brief excursion to the Bay of Biscay in 1760, and in January 1768 embarked from Ireland for Gibraltar where it was stationed until it was recalled to England in the autumn of 1775, arriving that December. During the American Revolution, the First Regiment was in the Caribbean, to which it sailed in 1780 and, in 1781, captured St. Eustatia, St. Martin and Saba. In 1782, it defended St. Christopher and Nevis and returned to England, then back to Ireland in 1784. It is highly likely that James’ father belonged to the First Battalion, but not necessarily one of the three companies named in 1752 as the respective companies likely rotated their barracks periodically. This regiment is not to be confused with the First Royal Foot Guards who were house troops and would not have been stationed in Ireland.

Regiment of Foot, Royal Scots, commanded by Lt. General James St. Clair, Colonel, has three companies in the First Battalion stationed at “Rosscastle” and lists the names of the Captain, Lieutenant, and Ensign for each. According to Historical Records of the British Army – Historical Record of the First, or Royal Regiment of Foot, the movements of the Second Battalion disqualify it as that of James’ father. However, the First Battalion was stationed in Ireland in 1749 through 1768, with a brief excursion to the Bay of Biscay in 1760, and in January 1768 embarked from Ireland for Gibraltar where it was stationed until it was recalled to England in the autumn of 1775, arriving that December. During the American Revolution, the First Regiment was in the Caribbean, to which it sailed in 1780 and, in 1781, captured St. Eustatia, St. Martin and Saba. In 1782, it defended St. Christopher and Nevis and returned to England, then back to Ireland in 1784. It is highly likely that James’ father belonged to the First Battalion, but not necessarily one of the three companies named in 1752 as the respective companies likely rotated their barracks periodically. This regiment is not to be confused with the First Royal Foot Guards who were house troops and would not have been stationed in Ireland.

With many soldiers stationed in such a beautiful spot, and likely on multiple occasions, it is understandable that a lonely redcoat would be attracted to a pretty Killarney girl, and likewise, which is what happened in this case. The adjacent uniform is that of the same regiment at this time.

In pleasant Kerry lives a girl,

A girl whom I love dearly,

Her cheek’s a rose, her brow’s a pearl,

And her blue eyes beam so clearly!

He long fair locks fall curling down

O’er a breast untouched by lover—

More dear than dames with a hundred pounds

Is she unto the Rover!

-An Spailpin Fanac, c1797

I have yet to do the research in Kew to find a name that sounds like “Gandsey” in the relevant records. As neither parent appears back in the stories of James’ life, it’s probable that they died afar, and his father perhaps in the American Revolution.

Today, Ross Castle is a semi-restored picturesque ruin that dates to the 1300s and was originally the stronghold of the O’Donoghue clan with flanking towers and protective outer walls. In June 1652, it was the last fortress in Ireland to surrender to Oliver Cromwell’s conquest of Ireland. Ross Castle was defended by Donough MacCarthy against Gen. Edmund Ludlow of the Parliamentary forces. It was believed that Ross Castle was impervious from the land, but Ludlow seized upon this belief and, in addition to attacking from the land, also attacked from the lake. The Ross Castle garrison ultimately surrendered. Shortly thereafter, the Irish land confiscations began under the Act of Settlement 1652, forever altering society and placing the vast majority of lands with Protestant English landlords.

Early Years

Gandsey was almost completely blinded in infancy by smallpox. Reportedly, his vision was enough to tell how many lit candles were upon a table. According to O’Neill, “The child evinced early genius for music, turning when absolutely an infant the reeds of the lake into musical instruments. When old enough, his grandfather sent him to one of the rustic schools where Latin was taught; and not only the master, but the pupils, loved to instruct and aid the precocious blind boy.”

Gandsey learned the uilleann pipes from Thady Connor, also blind and then the greatest piper in the area. Connor also gave Gandsey his pipes. The adjacent pipes and those below are Gandsey’s, formerly posted in Jimmy Brien’s Bar in Killarney, with the pictures found in a forum about uilleann piping. Gandsey likely played exclusively around Kerry in his early years. Around the age of 30, he became the piper for Lord Headley, where, according to O’Neill, “it was his privilege for many years to receive instruction beneath his lordship’s roof, where his fine original talents were applied to what was worthy of care and cultivation, and where his attention was riveted to the most exquisite melodies of the mountains and glens.” The first Lord Headley was Sir George Allanson-Winn, (1725-1798), an Englishman, who petitioned William Pitt the Younger for an Irish peerage and received one in 1797 in Aghadoe. George’s wife, Jane Blennerhassett, was a descendant of the Conway family from County Kerry. George was succeeded by his son, Charles (1784-1840) and his wife, Ann Matthews, who were thus the Lord & Lady known to James. Writers refer to Gandsey living in Aghadoe House, the Headley’s mansion. Said Hall, “He was greatly loved by his patron, and respected by all his neighbours; and, fortunately, his Lordship did not die without making some provision, though limited, for his venerable protege.” Lord Headley died 1840, and in the 1851 valuation “James Gandsey” is seen living on the property of “Lady Headley” at Aghadoe House as a separate tenant in his own house in Knoppoge Townland in the Aghadoe parish.

King of the Kerry Pipers

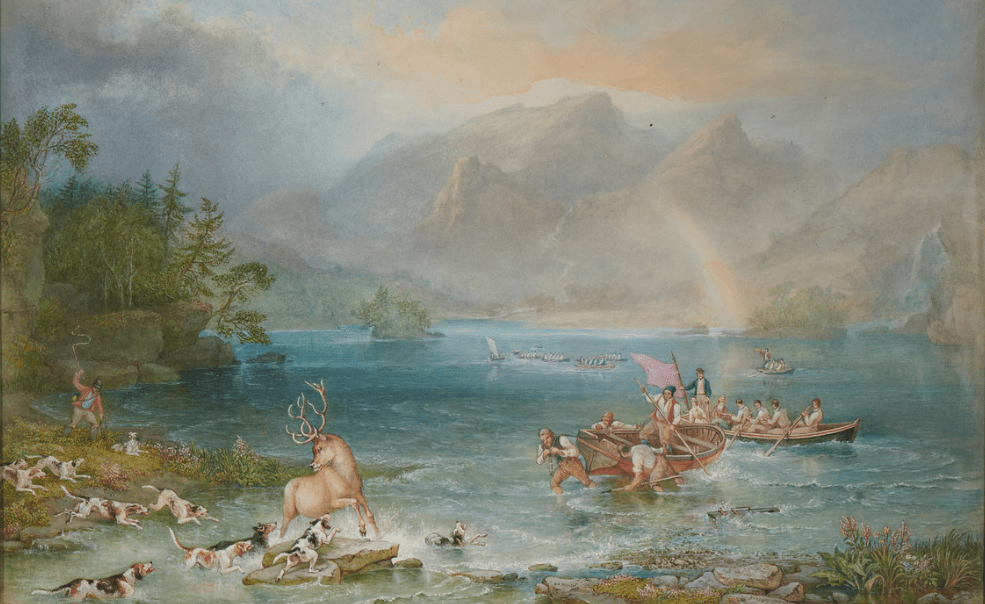

Gandsey was certainly a fixture in Killarney, where he earned fame both locally and from farther afield as people and writers travelled through Kerry – seeing him at an inn, the Halls “record it among the greatest treats of our lives.” Georgina, Lady Chatterton in Rambles in the South of Ireland (1838) recalled that “The stag hunt on the lakes was the great feature of the day. Lord Headley had kindly arranged that we should go to it in his barge; we thus had the advantage of his Piper, the celebrated Gandsey, who figures in Crofton Croker’s Killarney Legends, and whose touching and beautiful strains have enchanted so many tourists.”

had kindly arranged that we should go to it in his barge; we thus had the advantage of his Piper, the celebrated Gandsey, who figures in Crofton Croker’s Killarney Legends, and whose touching and beautiful strains have enchanted so many tourists.”

Beyond the mastery of the instrument, and his ability to compose, was his encylopedic knowledge of the music. Said Hall, “Gandsey is, moreover, a library of old Irish airs; his treasure is inexhaustible.” He combined this with a keen wit and charming character that dominated every performance, leading to comments that he was “unrivaled in his day” and a “venerable bard.” The Halls said that “to hear him play is one of the richest and rarest treats of Killarney. Gandsey is old and blind; yet a finer or more expressive countenance we have rarely seen. His manners are, moreover, comparatively speaking, those of a gentleman... It would be difficult to find anywhere a means of enjoyment to surpass the music of Gandsey’s pipes.”

At some point along the way, his eldest son and our ancestor, George, accompanied him on violin, and is referenced often in the great deal of press between 1840-1854 when they traveled throughout Ireland, Scotland and England. Among other things, they played both traditional airs and jigs.

The following passage by Hall describes the general experience of seeing them play:

The door opens and the blind old man is led in by his son: his head is covered by the snows of age, and his face, though it retains traces of the fearful disease which deprived him of sight, is full of expression. His manner is elevated and unrestrained-the manner of one who feels his superiority in his art, and knows that if he do not give you pleasure, the fault is not his. Considering that perhaps you do not understand sufficiently the beauty of Irish minstrelsy, he will test your taste by playing some popular air or quadrille; and you already ask yourself if you are really listening to the droning bagpipes. His son accompanies him with so much taste and judgment on the violin as to cause regret that he is not practiced on his father’s instrument, for you would have the mantle hereafter – and long hence may it be – descend upon the son.

You ask for an Irish air, and Gandsey, still uncertain as to your real taste, feels his way again, and plays, perhaps, `Will You Come to the Bower?’ so softly and so eloquently that you forget your determination in favor of ‘original Irish music’ and pronounce an ‘encore.’ Do not, however, waste any more of your evening thus; but call forth the piper’s pathos by naming `Druimin dhu dheelish,’ as an air you desire to hear; then observe how his face betrays the interest he feels in the wailing melody he pours not only in your ear but into your heart. “What think you of that whispering cadence-like the wind sighing through the willows? What of that line-drawn tone, melting into air? The atmosphere becomes oppressed with grief, and strong-headed, brave-hearted men feel their cheeks wet with tears. Some of the martial gatherings are enough to rouse O’Donoghue from his palace beneath the lake – one in particular, `O’Donoghue’s whistle,’ is full of wild energy and fire.

In but too many instances these splendid airs have not been noted down. The piper learned them in his youth from old people, whose perishing voices had preserved the musical traditions so deeply interesting – even in an historical point of view – to all who would gather from the wrecks of the past, thoughts for the future. There are few of those memories of by-gone days that Gandsey does not make interesting by an anecdote or a legend; and in proportion as he excites your interest, he continues to deserve it.”The instrument on which he performed to the great delight of Mrs. Hall, and in fact all who ever heard him, was a bequest from his friend and instructor, Thady Connor, who asserted Gandsey was the only musician in that part of the country worthy to inherit so precious a gift. When questioned as to the accuracy of the authority for a certain story, the kindly old man smiled and bowed but made no verbal reply. As he did not express any doubt concerning its truthfulness, we may as well repeat the story as told to the amiable authoress by no less a person that Sir Richard Courtenay himself, in a chapter devoted to “Irish Pipers in Literature.”

Acclaim

Kerry Evening Post, February 22, 1840

“LORD AND LADY HEADLY. On Monday, the 17th instant, the tenantry of the noble, Lord, resident at Aghadoe, met enlarged numbers on that beautiful and commanding eminence in order (we quote the words of Mr. John Gandsey, our correspondent on the present occasion) “to testify their gratitude to Lord and Lady Headley, on the auspicious occasion of his Lord ships restoration to health.” so early as 7 o’clock in the morning, horses and carts were an active requisition, laid in with turf and guitar barrels for the erection of a bonfire on a scale worthy of an event which has brought joy and comfort to many of poor man’s heart, and unmixed pleasure to all. The utmost good order characterize the proceedings of the day, which ushered in a night of no ordinary festivity. No sooner did the bonfire fling its broad light over the surrounding lowlands, then thousands of the peasantry flock to the joyous beacon. Our Kerry Carolan, the inimitable Gandsey and his son struck up the merry pipes to the inspiring sound of which the multitude, with their hearts in their heels, footed the agile and graceful dance of our country. To give more eclat to the demonstration, cannon were fired off at intervals. In short, what with the music and the dancing, the stupendous bonfire, the roar of the cannon echoed and re-echoed from the surrounding mountains, the hearty cheers and warm prayers for the health and long life of the best Landlord in Ireland and that of his incomparable Lady, the entire was calculated to give a joyous excitement to all who witnessed it, and to present a fine practical illustration of the good effects of non-absenteeism. The multitude retired the following morning to their homes, full of the warm feelings, which had led them to assemble on this very interesting occasion. The letter conveying these details, and which we have compressed in our own language, is signed by John Gandsey, for himself and fellow tenants.”

Caledonain Mercury Edinburgh, December 16, 1841

“MR GANDSEY’S CONCERT. On Monday evening, Mr. Gandsey, the justly celebrated Irish menstrual, gave a concert in the Hopetoun Rooms, which were crowded by a highly fashionable, and, we venture say, a most delighted audience. Mr. Gandsey, on his entrance, was greeted with a warm reception. His appearance is extremely interesting, and although age has deprived him of the light of other days the soul of music seems prominently delineated in every feature of his vulnerable countenance. We were all together on prepared to listen to the soft melodious tongues which he produced from the pipe of the Emerald aisle – indeed, we fully anticipated something a very inferior and different cast. “Co lun” “Sprig of Shillelah” “Savourneed Dhelish””The House under the Hill” “Go where the Glory Waits Thee” “Garry Owen” and various other national airs, were performed in a style, which combined the greatest taste with the most brilliant execution in precision. We sincerely hope that Mr. Gandsey will be induced to give another concert in the Scottish metropolis before he takes his departure for the classical wilds of Killarney, satisfied, as we are, that many who heard his performances on Monday evening, would embrace the second opportunity of listening to the thrilling strains of his melodious and heartstring pipe.”

Freemans Journal, Dublin, February 22, 1842

“the menstrual of Killarney gives a concert this evening at the music hall, comma and every lover of Irish music in Dublin ought to flock to the spot. They will there find a treat in our national minstrelsy that there are a few opportunities here of enjoying. The following extract from a letter by Wilson, the celebrated vocalist, written after a visit to the lakes of Killarney and lately published in a scotch paper maybe red with interest – ‘Young Gandsey, a very intelligent, pleasant fellow, promised to bring his father who has long been the most celebrated Piper in the neighborhood of Killarney, to let us hear the Irish pipes played in perfection and certainly I never enjoyed an evening more in my life. I was riveted to old Gandsey for nearly 4 hours by the delicious manner in which he played the airs of old Ireland. He gave them a sweetness and a character, such as I never heard given them before. He is a Rev. looking old gentleman with lint white locks, and seems to reveal in his own exquisite music. After playing many slow errors, he played what he called the Killarney fox hunt with prodigious effect. It was an extraordinary performance, first the horn sounds to unkennel the hounds, then there is the beating about for the fox, at last the Huntsman joyfully cries out the fox! The fox! Then the hounds break loose with a tremendous halloo. After a hard run, they lose him! The horn sounds to gather in the hounds, there he is again! To the lake! To the lake! He’s off to the Gap of Dunloe! He’s lost! He’s earthed! Then comes the song of lamentation for the loss of the fox, the hounds are drawn off, the Huntsman dance down the hill to the fox hunters jig. The effect he produced by his enthusiastic, shouting to the hounds – by the imitation of the yelping of the dogs – the shout – the general confusion of a fox hunt – and by the song of lamentation –is really extraordinary. No one, without hearing it, would believe that such an effect could be produced by so small and so sweet toned in instrument.

Dublin Morning Register, March 7, 1842

“GANDSEY’S CONCERT. We were very much pleased to see one of the largest attendances we ever behaved in the music hall last evening. Gandsey is one of the few that remained to us – these legacies of the ancient time – these types of the bars to whom we owe all that we are present possess of the glorious melodies of our country, and as such deserves well of the metropolis of Ireleand; we, therefore say we are pleased that such a manifestation of the good taste of the citizens of Dublin. It were vain to attempt to give an idea of the effect produced by the fine old man himself; the pipes are instruments, scarcely loud enough for the area of the music hall, but the desire of hearing the exquisite playing of Gandsey produced so profound as stillness that even the comparatively weak instrument told it was only, however, when the old man’s voice was heard – when his countenance was lighted up – when the genuine Irish humor broke out, that the enthusiasm of listeners rose to its acme. We never saw a more thoroughly sympathizing audience than the one last night when listening to his “Fox Chase.” We would have been wrath were they not so comma, especially when he bent forward and with every feature beaming with wagon humor, he swore as the fox – “it was a leg of a salmon I took.”

Kerry Evening Post, September 10, 1842

“the principal attraction of the meeting was the performance of our far famed, countryman, Gandsey, the celebrated Irish Piper, and his son. Lady Dunraven said that the music was the sweetest that she had ever listened to. We are glad to find that our countryman is continuing to add more laurels to his already established fame. He has lately been delighting the canny Scots with the witchery of his strainson the Union Pipes, and is shortly to visit Liverpool.”

Dublin Weekly Reporter, September 17, 1842

“STAG HUNT. The stag hut at Cahirna wood, on Monday, was the finest this season. A splendid two year-old stag was started at the entrance of a long Glen near the top of the upper lake; dashed along it, and up the hill towards the Police Berwick; doubled around the wood to Derricunihy cascade; repeated the same course several times; and at last dropped down with pure fatigue on Derricunihy quay, just as he was about to plunge into the water. Roche never witnessed such sport and denies that Gandsey and all the Piper’s in Ireland, and the Highlands and islands of Scotland together could equal the delightful music of the Muckrus hounds.

Kerry Evening Post, January 4, 1843

“CHRISTMAS FESTIVITIES AT VALENCIA. Our great Piper, Gandsey, the prince of Piper’s, has been passing the holidays with the Knight of Kerry at Glenlean. After deleting the guests, there for some days, he was requested by the inhabitants of Valencia in general to give them an opportunity of dancing out the old year, and in the new one, to his heart cheering pipes. It came off most successfully at a large store, we’re about 100 danced in celebration of the season. The place was lighted by the patent lamps from Mr. Blackburns engine house and the happy night passed off to the high gratification of all parties. Gandsey left Valencia on Sunday, for Killarney.

Cork Examiner, January 29, 1849

“THE SISTER OF CHARITY – Mr Gandsey, the gentleman whose musical acquirements have, as it were, perpetuated the fervid feelings and piosly enthusiastic sentiments of the departed poet (Gerald Griffin), by thus happily allying them with sacred song, is also an Irish comment, but sometime denzien of Dublin, but at present located in London, where he enjoys a high reputation in his art, which the excellence of this, his last composition cannot fail to augment most material. To the lovers of sacred Melody, this composition will prove a welcome novelty.”

Dublin Evening Packet, September 18, 1849

“An evening at the Kenmare Arms, Killarney…At the head of the room, in all the pomp and circumstance of bagpipe bardhood, sat the venerable Gandsey. As the gay old, brave and hearty minstrual, for he is as felicitous at capping lines from the classics as at the chanter once announced himself in a political medley compiled from the Latin poets. Beside him sat Young Gandsey, the company, his father with the violin now in those plaintive national melodies to which the finger of that blind old man gave such expression now in the humorous and rollicking planxty and anon in the never to be forgotten “Moddereen Rue” that most unique fantasy in which the various windings of the CHASE, the cry of the dogs, the horn of the Huntsman, the shouts of the hunters are so graphically blended. The recitative announcing the death of poor Renard, and the “Fox-hunters Jig” Recording at once the termination of the sports of the field and recant of the evening’s jollification in which our buckskin fathers rejoiced..”

Cork Examiner, May 3, 1854

“That evening we listen to the fine music of Gandsey, the celebrated Irish Piper, a truly vulnerable man, very old, and quite blind, who plays his native melodies with touching express expression, waking the old sorrows of Ireland, and making them wail again, and giving proud voice to her ancient glories, do you believe that her loss nationality is not dead, but sleepeth, and must yet rise to free and powerful life.”

National Library of Ireland

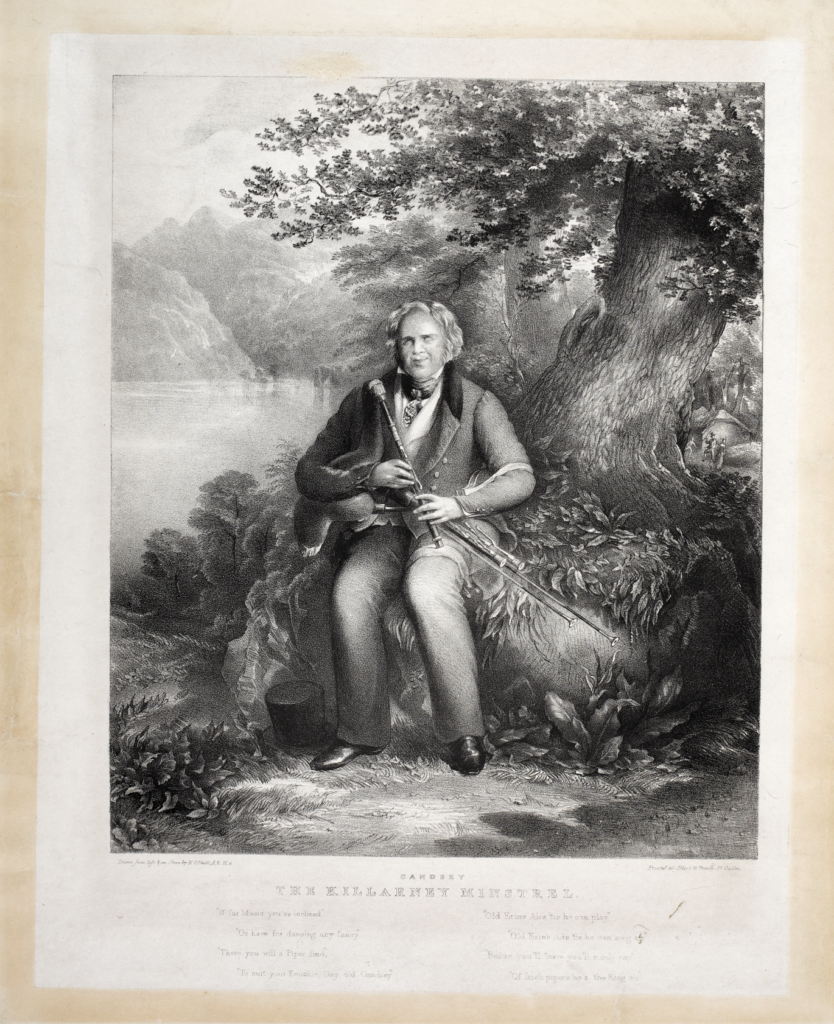

GANDSEY – THE KILLARNEY MINSTREL.

“If for Music you’re inclined”

“Or have for dancing any fancy”

“There you will a Piper find,”

“To suit your Knuckle, Gay old Gandsey”

“Old Erin’s Airs ’tis he can play”

“Old Erin’s Airs ’tis he can sing air”

“Before you’ll leave you’l surely say”

“Of Irish pepers he’s the King air”

– Drawn from life & on Stone by H.O’Neill, ARHA. Printed at Allen’s 16 Trinity St. Dublin

Stories

We are fortunate to have a sense of James Gandsey through stories published by contemporaries, complete with all the insight and enjoyment of actual dialogue.

“No, not to-morrow, Mahony, I am going on the lower lake — but what music is this?”

I listened more attentively, and heard an excellent performer indeed.

“Waiter, who is the bagpipe player?”

“O, sir, that’s Mister Gandsey, Lord Headly’s own piper — if you want real music, sir, ’tis he that can give it to you in style.”

“What Gandsey, of whose pipes I have heard so much! — pray tell Mister Gandsey I shall be most glad of his company.”

The person thus invited soon made his appearance: he was blind, and entered the room leaning on his son; but though blind, the light of genius beamed from his countenance, so as to render his want of sight scarcely perceptible. In addition to Gandsey ‘s talents as a musician, (which, if not of the highest, are of a highly respectable order) he can tell a good story, sing a good song, and cap Latin verses with any man in the classical County of Kerry.

I had a most delicious evening with Gandsey and his pipes. He played for me one old Irish air after another, accompanied with much skill and taste by his son on the violin; and he told me their traditionary histories.

“Good night, Gandsey — good night, I hope to see you again to-morrow — many thanks for your music — Bless me, ’tis just twelve o’clock, I did not think it was ten; really you have given additional wings to time.”

“Much obliged to you, sir — good night, sir.”

**********

A stag hunt creates quite a sensation in Killarney; on such occasions the town pours forth almost its whole population. Sometimes the stag makes his escape up the mountains, leading hound and hunter a long and weary chase. On this occasion, however, matters were better managed; for the stag, after several vain attempts to ascend, made his appearance, and ran along the river’s side for nearly a mile, in full view of the boats and those on the shore, till, finding himself too closely pressed by the hounds, he plunged into the river. Then came the struggle, the chase, and the race, for the honour of taking him, which was at length done by Mr. O’Connell. A handkerchief was bound round the poor animal’s eyes, his legs tied, and, thus secured, he was lifted into the boat. The boat then put in to the shore, in order to allow every one a peep at the stag; to obtain which, the fleet gathered round, and all hurried towards one point on the shore, where soon stood nobility and mobility, huntsman and peasant, indiscriminately grouped together. Close to Mr. O’Connell’s barge was that of the Earl Kenmare, into which stepped the round, rosy, and reverend Lord Brandon, at the same time, apparently, addressing some courtly compliments to the Lady Kenmare — then there was the good Lord Headley with his famous piper, and my worthy friend Gandsey.

**********

We dined; and, after a well-served dinner, Gorham made his appearance, to inquire if I would wish for Gandsey’s company?

Gandsey entered, as on a former occasion, leaning upon his son. “Ah, Gandsey,”said I, “this was very good of you to come to me, especially as it is my last evening in Killarney.”

“I thank you, sir,” was the modest reply of Gandsey; “you are very good, sir.’

“Here is a glass of wine — but perhaps you would prefer some whiskey punch?”

“I drink the wine to your honour’s good health and long life,” said Gandsey; “but the whiskey punch, sir, if you please, harmonizes better with the melodies I am going to play, sir.”

“Waiter, some whiskey punch. — Gandsey, I wish much to hear ‘the Eagle’s Whistle’ so I think the war-march of the O’Donoghue is called — Yon can play it, of course.”

“Without any kind of doubt I can do that same,” returned Gandsey. “Boy, is your violin in tune? There’s the note — Week — week — week — squeek — that will do. Now, sir, — but first, if you please, suppose, sir, that I give you, because, you see, it is the oldest of the two war-marches of the O’Donoghue, the Step of the Glens'” (Here Gandsey played the barbarous strain)

“Oh, ’tis the O’Donoghues were the boys that could stir their stumps down the side of a mountain,’ said Gandsey, when he had concluded. “And now, sir, here’s the Eagle’s Whistle; that was their other war-march, you know. Boy, tune up that note a leetle higher.” (Here Gandsey played the melody)

“Gandsey,” said I, “it is easy to prophesy, that the fame of your Eagle’s Whistle will go forth, alight as beard of thistle.’

“How close is the resemblance,” remarked Mr. Lynch, “between the Irish and Scotch pibrochs. I remember”— and he was about to proceed with, I have no doubt, some interesting reminiscence or remark, had not Gandsey run his right hand up the pipe, with Tir-a-lee-ra-tir-a-lee-ra-lee-BOOM.

“Come, Gandsey,” said I, “another tune, if you please — but something with a history to it.”

“I’ll give you, sir,” said Gandsey, “the lamentation for ‘Myles the slasher,’ a real ould air of Erin.” (Here Gandsey played the melody)

“And now,” said I, when he had concluded, “now for the history.”

“Why, you see, sir,” said Gandsey, placing the pipes at rest upon his left knee, “why, you see, sir, Myles the slasher was an O’Reilly — and if he was, he was like every one of the same name, fond of Erin, for she was his country. Well, sir, when the bloody Cromwellian wars were going on, you see, Myles the slasher headed his clan, and died like a brave commander, defending the bridge of Finea, in the County Cavan, against that robbing and murdering thief of the world, Cromwell. ‘Twas a fine death he had; and ’tis as fine a tune that I’ve played for you, sir, to keep his memory up among the people, as can be, in my opinion. But if he did die all covered with wounds, ’twas on the flat of his back that Myles O’Reilly the slasher was laid, with a thousand voices after him,

Up! away, away! —

Light as beard of thistle;

‘Tis the morn of May —

Sound the Eagle’s Whistle!

In the monastical church of Cavan, though ’tis since destroyed, to build a horse-barrack; and these were the very words that were carved out over him, upon as beautiful a gravestone as could be: “LECTOR NE CREDAS SOLEM PERIISSE MILONEM HOC NAM SUB TUMULO, PATRIA VICTA JACET.”

“This lamentation pleases me so much, I hope, Gandsey, you can favour us with another.”

“Oh, that I can, sir, lamentations in plenty — for sure ’tis little else is left, for green Erin or her children, but sorrow and —

“Whiskey,” said Mr. Lynch.

“True,” said I, “we have justly been called ‘a persecuted and hard-drinking people.’ ”

“But the lamentation,” said Mr. Lynch.

“Tis the widow’s lamentation,” said Gandsey: “You see her husband, one William Crottie, was hanged through the means of one Davy Norris, a thief of an informer, who came round him, and betrayed him. And so Mrs. Crottie, whose own name was Burke, a mighty decent woman she was, and come of decent people, made up this lamentation about her husband.” (Here Gandsey played the melody)

“And now, Gandsey,” said I, “mix yourself another tumbler of punch, and then let us hear an Irish melody with something more of sentiment in it, than the singular strains you have already played. Suppose some ditty, which an unfortunate lover might sing to the mistress by whom he was neglected and abandoned. You have an air of this description, I doubt not, Gandsey, for such heart-breaking affairs must have happened in Ireland as well as elsewhere.”

“Oh, plenty of them, sir,” said Gandsey; and he immediately commenced the melody.

“Yes, that is Irish — truly — intensely Irish,” “how exquisitely the violin accompaniment harmonizes with the pipes. Pray, whose arrangement is that?”

“Twas I, sir,” replied Gandsey, “just fixed it out for boy to learn.”

“Have you any words to this melody?” inquired Mr. Lynch.

“None, sir,” said Gandsey, “though they’re much wanting to it; but I have some words of own making too, which I’ll sing, with the greatest pleasure in life, to the air of ‘Bob and Joan.’ Come, boy, scrape away.”

“Bravo, Gandsey,” said I. “Bravo,” echoed Mr. Lynch. “You must be thirsty from your exertions. ‘Gansey, to promote, Harmonious tunes so jolly.’ So here are the materials for another tumbler of punch. You want something?”

“Water, if you please, sir, — for what is whiskey punch without the water is screeching hot, and just sings to you like a Banshee?”

“Do you hear the unearthly music of Gandsey’s glass,” remarked Mr. Lynch, as the boiling water made a kind of musical murmur within it — and he continued, while Gandsey sipped the boiling mixture — “I never hear that simmering, without mentally recurring to an incident which recently happened to me. It was with a feeling of content and pleasure, that on the Christmas eve of 1826 I gazed around my cottage kitchen, and saw that it was duly decked with holly; the dark green leaves and red berries mingling fantastically with the bright tin vessels which hung upon the white walls….”

**********

“A story does not lose by your telling, Lynch. And now, Gandsey,” said I, “suppose you —

“There’s a tap at the door, sir,” said the younger Gandsey, laying down his violin which he had just assumed.

“Come in — come in, Gorham.”

“Sare,” said Gorham, ” I have taken the liberty — of — “and he bowed, and held forth a book, “asking your opinion of my establishment.”

“Gorham,” said I, shrugging my shoulders like a Scotchman, you must first let me see your bill. I cannot say anything at present, beyond my having enjoyed myself very much, and having nothing to complain of; but gold may be bought too dear, you know.”

With another bow, Gorham made his silent exit.

“And now, Gandsey, I am all attention.”

“To what ?” said Mr. Lynch, “you have heard Gandsey’s unrivalled performance on the pipes; you have heard him, moreover, sing a song of his own composition: now which do you wish to try Gandsey — at capping Latin verses, or hear him tell a story ?”

“‘My Latin, Comes not so pat in” — as it did formerly,” said I, “therefore, Gandsey, as Mr. Lynch will put you through your paces, suppose — since I at once confess myself unequal to the trial of classical skill which has been proposed — you tell us the story/’

“As you will, sir,” replied Gandsey, carefully putting his pipes aside.

“But your glass is empty — that will never do.’

“I thank you, sir, for your consideration. Well, sir, no doubt you are a great traveller, and have seen many strange places; but if ever you travelled like myself, some twenty years ago, from Cork to the raking town of Mallow, you’d remember the spot of Kelleher’s farm, to this hour, or I’m much mistaken. At that time (may be ’tis now rather better than twenty years) the man who took the new road, from the blessed moment he turned his back on the old red forge at the end of the beautiful Blackpool, if it was not for the new slate-house, close to Kelleher’s bound’s ditch, might have gone thirsty enough into the town of Mallow, with his throat as dry as any powderhorn of a midsummer’s day; your honour’s good health, sir.”

“Thank you, Gandsey.”

“For you see, sir, there was but the one place of entertainment to be met with. And a real beautiful painted sign it had up over the door, of three pots of porter, with their white heads on them like any cauliflowers, and underneath was painted out, in elegant large letters, ‘ENTERTAINMENT FOR MAN AND HORSE’

“The place was called Lissavoura, and the same name was on Paddy Kelleher’s farm, for I was never the man to forget the name of the place I was well treated. Well, one morning, about eight o’clock, Kelleher was standing by the side of a bog-hole, and scratching his head….[long story]

…”So Kelleher went home to his own house, and his wife was kind and quiet of tongue; and the priest ever after was as civil to him as may be, and all for fear he’d spake about the fat pig.

“There’s my story for you”— said Gandsey.

“Well sung, Gandsey”— said Mr. Lynch. — “Here, mix yourself another fumbler of tunch — tumbler of punch I mean — Irish whiskey is good — Irish songs are good — Irish music is good — Irishmen are fine fellows — fine fellows — ’tis a fine country — (hiccup) — a fine country.”

“Tis true for you, sir”— said Gandsey — “very true for you.”— And here, altho’ I am perfectly unable to account for the fact, my recollection of what followed completely fails me.

Death

James died at the age of 90 in 1857, just a few short years after his traveling performances. His buried on his beloved Lough Leane, at Muckross Abbey alongside other notable Kerry poets. According to a 1988 article in The Kerryman, a plaque was hung in James’ honor in the 1970’s by some descendants in conjunction with the Killarney branch of Comhaltas Ceoltoiri and Jimmy O’Brien (of the Killarney bar). Founded in 1448, the Abbey’s stout ruins still stand today, and were on lands owned by the Herbert family.

The Piper’s Family

With the unique surname, Gandsey, there has been much correspondence amongst the current extended family, and I’m in possession of a stack of documents from my maternal grandmother, a Gandsey, and her brother, George. The oldest son of James (the piper) and my ancestor, George, whose violin accompanied his father’s pipes, had noted on his death certificate in Wisconsin that his mother’s name was “Margaret Barry.” Names were often recorded in Latin in the parish registers, so Margaret would be “Margaritam” as George was “Georgii” and Forbes was “Forbus” etc. A marriage record for James and Margaret has yet to be found, but we know that they had six children and perhaps at some point the naming conventions will give clues to the parentage of both James and Margaret. Their children, in order, were: George, James, Forbes, Catherine, Margaret, and Ellen.

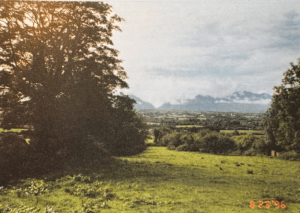

George (June 1, 1810 – October 14, 1888) was the eldest son and, as noted above, accompanied his father on violin. At some point, George became a farmer, ultimately acquiring 95 acres (and 0 rods, 22 perches) in Ballybrack Townland, Aglish parish, eight miles to the north of Ross Castle. From the front door of his farmhouse ruins, one can still see the Gap of Dunloe in the adjacent photo from August 1996. George’s diary noted that the farm had pigs, cows, butter, fowl, grains, hay and vegetables. George married a girl from adjacent Cork County, Mary Ellen Sweeney, on February 21, 1841, in Currow (Kerry) about six miles to the Northeast of Ballybrack. Their first child, Mary Ellen, was born in 1841 and eight other children followed between 1845 (Hannah) and 1865 (Miles). The great Irish famine spanned 1845-1852, but Kerry was suffering by 1835 economically due to risky dependence on the potato and land tenant issues, with much of the population living in severe conditions. Their family made it through the hardest time. As recorded by an immediate ancestor of one of the children, an event happened in 1867 that changed the course of the family. Mary Ellen and Hannah told their mother that they were going to visit another farm, but they didn’t come back that day. The following day, other children went searching to no avail. The next day, the parents went to their church to pray, where they were shocked to learn from the priest that he’d married Mary Ellen to a local farm boy and they’d gone to Queenstown (present day Cobh, or “cove,” in Cork) to board a ship to America. Mary Ellen’s immediate sister, Hannah, who was very attached to her, accompanied her on the trip. Then, in the Spring of 1869, George & Mary Ellen received a letter from Mary Ellen from Wisconsin – “would you come over here to visit Hannah as she is too sick to travel and she has a very short life ahead of her.“

George (June 1, 1810 – October 14, 1888) was the eldest son and, as noted above, accompanied his father on violin. At some point, George became a farmer, ultimately acquiring 95 acres (and 0 rods, 22 perches) in Ballybrack Townland, Aglish parish, eight miles to the north of Ross Castle. From the front door of his farmhouse ruins, one can still see the Gap of Dunloe in the adjacent photo from August 1996. George’s diary noted that the farm had pigs, cows, butter, fowl, grains, hay and vegetables. George married a girl from adjacent Cork County, Mary Ellen Sweeney, on February 21, 1841, in Currow (Kerry) about six miles to the Northeast of Ballybrack. Their first child, Mary Ellen, was born in 1841 and eight other children followed between 1845 (Hannah) and 1865 (Miles). The great Irish famine spanned 1845-1852, but Kerry was suffering by 1835 economically due to risky dependence on the potato and land tenant issues, with much of the population living in severe conditions. Their family made it through the hardest time. As recorded by an immediate ancestor of one of the children, an event happened in 1867 that changed the course of the family. Mary Ellen and Hannah told their mother that they were going to visit another farm, but they didn’t come back that day. The following day, other children went searching to no avail. The next day, the parents went to their church to pray, where they were shocked to learn from the priest that he’d married Mary Ellen to a local farm boy and they’d gone to Queenstown (present day Cobh, or “cove,” in Cork) to board a ship to America. Mary Ellen’s immediate sister, Hannah, who was very attached to her, accompanied her on the trip. Then, in the Spring of 1869, George & Mary Ellen received a letter from Mary Ellen from Wisconsin – “would you come over here to visit Hannah as she is too sick to travel and she has a very short life ahead of her.“

George and Mary Ellen were certainly distraught. They survived the great famine, they loved Kerry, and they had a relatively large farm – but they had seven children still in Ireland, including five boys. The land simply couldn’t support a family this large. George’s notebook also recorded a Daniel McSweeny’s address in Chicago, so Mary Ellen had family in America. The girls’ letter from America was the catalyst. They acted quickly, settled accounts, and sold the farm. On June 16, 1869, George ran the adjacent advertisement in the local Tralee Chronicle. He praises land agent, landlord, the new tenant, and makes a strong political statement regarding these relationships. Hussey was the land agent to his brother-in-law, the Knight of Kerry, Sir. George Colthurst. The Honorable Lady Cecilia Yorke was the landlord after the death of her husband, Henry Galgacus Redhead Yorke (quite a name, and he had quite a history), but the lands came from her family – she was born Elizabeth Cecelia Crosbie, daughter of William Crosbie, 4th Baron Brandon, whose family was a major Irish landowner.

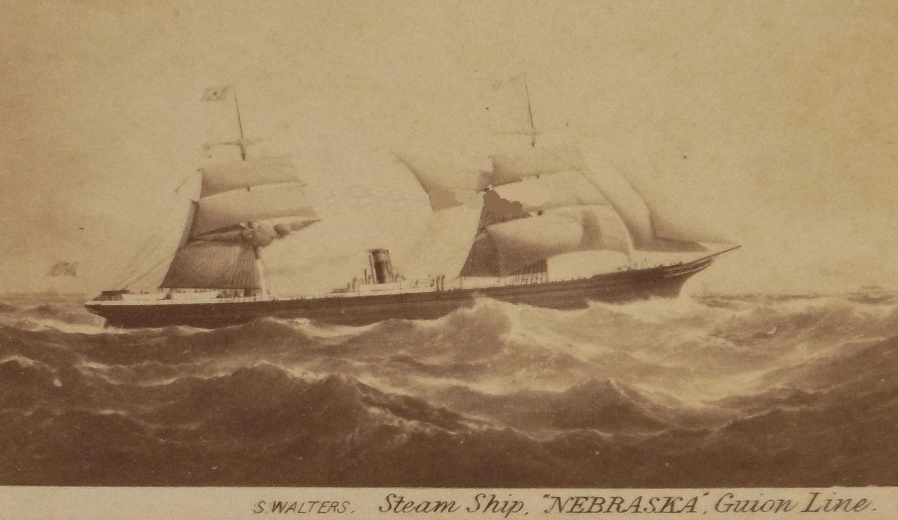

On June 23, 1869, George left Ballybrack with Mary Ellen and seven children, arriving in Cork on June 24, sailing from Queenstown on June 25, 1869. They arrived in New York on July 7, 1869 on the Guion Line’s steamship NEBRASKA, 368 feet long, single-screw iron ship built in Newcastle upon Tyne in 1867 by Palmer’s Shipbuilding and Iron Co. They crossed the Hudson River and departed by rail in New Jersey on July 9 and arrived in Marinette, Wisconsin, on July 15 with multiple rail and boat transfers in between. On July 24, 1869, George began work in a sawmill in Marinette, which sits on the Canadian border just to the north of Green Bay. Hannah died in Marinette on October 13, 1869 – thankfully, the tremendous effort to uproot the family from Ireland and move them to America had paid off in time to see Hannah before her death.

George died on October 14, 1888 in Florence, Wisconsin. His death record gave his birthday as June 1, 1810 and said his age was 78, which aligns. The record also gives the name of the father and mother of the deceased as “John Gandsey” and “Margaret Barry.” This naming of “John” contradicts the record of the name “James” as a tenant to Lady Headly. All of the press clippings above fail to use a name other than “Mr.” or just “Gandsey” except the first one, from Kerry, that says it was “John Gandsey” in attendance at the 1840 celebration for Lord & Lady Headly. T. Crofton Croker, a contemporary and friend of Gandsey, recorded the stories above in his 1853 Killarney Legends – A Guide to the Lakes. At the very end of the book, the last bit of text, is a fully published letter signed:

“JAMES GANDSEY, Lord Headley’s Piper”

If George named his second son “James” and no sons “John”, then both the death record and the Kerry article are mistakes – or, perhaps, the piper’s name was John James Gandsey and he was known by both first and middle and thus more frequently as just “Gandsey.”

James (junior) was a black sheep that must have caused unfathomable shame to the family, especially his father whose name he carried. Why? As the potato famine set in during 1835, on top of existing economic hardship, James – at the age of 23 – was convicted for stealing Lord Headly’s wine at Aghadoe. The benevolent benefactor, who took James the piper into his residence, and gave him so much, saw one of James’ sons turn around and steal from the hand that fed them. The Limerick Chronicle of April 8, 1835, recorded: “…and James Gandsey, charged with stealing wine the property of Lord Headly, were convicted at Killarney Sessions, and sentenced to 7 years transportation.” As for the “transportation,” he was sent to Australia as a convict, which can be seen in the records with James (junior) as prisoner No. 1074 arriving on the HIVE in a spectacular way, having shipwrecked with no lives lost. Later, after his term was up, we see a new address for James (junior) in his brother George’s 1869 notes – “Westbury Farm, Jacob’s River near Invercargill, New Zealand.“

James (junior) was a black sheep that must have caused unfathomable shame to the family, especially his father whose name he carried. Why? As the potato famine set in during 1835, on top of existing economic hardship, James – at the age of 23 – was convicted for stealing Lord Headly’s wine at Aghadoe. The benevolent benefactor, who took James the piper into his residence, and gave him so much, saw one of James’ sons turn around and steal from the hand that fed them. The Limerick Chronicle of April 8, 1835, recorded: “…and James Gandsey, charged with stealing wine the property of Lord Headly, were convicted at Killarney Sessions, and sentenced to 7 years transportation.” As for the “transportation,” he was sent to Australia as a convict, which can be seen in the records with James (junior) as prisoner No. 1074 arriving on the HIVE in a spectacular way, having shipwrecked with no lives lost. Later, after his term was up, we see a new address for James (junior) in his brother George’s 1869 notes – “Westbury Farm, Jacob’s River near Invercargill, New Zealand.“

The youngest four children – Forbes, Catherine, Margaret, and Ellen – all went to Boston, Massachusetts. George’s diary recorded their addresses in 1869 when he was coming over. Forbes lived at 45 High St. in Boston, Margaret at 75 Cherry St. in Cambridge, and Catherine (Cate) at 79 North Margin St. in Boston.