Edward Robinson

1616-1690

In a time of often prolific records, how did Edward Robinson manage to avoid appearing in New England for very long periods of time over his life, yet accumulate a “manshion house” on 40 acres of land near The Common in the middle of Newport, Rhode Island by 1686? How did Edward reach sufficient stature to sit on four General Court of Trials on the Grand Jury with Governors Coddington & Arnold and all the other leading citizens on the court – including Clarke, Cranston, Coggeshall and Roger Williams? Why did he leave two very young sons born out of wedlock to the care of three friends in Newport, and leave these sons all of his Newport assets in trust? Why did he never return to Newport? Where is he buried? Where did he come from? To tell Edward’s story, I am including recorded facts regarding his time in Rhode Island, and I am also including facts that fill in the voids and suggest his life was anchored in, and ended in, Barbados – where he first sailed as an indentured servant at the age of 18 in 1634.

Newport-Barbados Connections

At this time in New England, the entire economy was built upon the provision of goods to support the Caribbean plantation system. The movement between Newport and Barbados, in particular, was so frequent and pervasive that people simply drop from the records of one location, only to show up in the other. In the first year of Barbados settlement in 1627, even the governor of Massachusetts Bay, John Winthrop, sent his son, Henry, to Barbados for two years. The Rhode Island Historical Society, in its Index to the Early Records of the Town of Providence, says:

“Many of the early emigrants from England first settled at Barbados and from there came to New England, and vice versa. For example, in 1647 Peter Tallman came from Hamburg, Germany, to the Island of Barbados. About 1650 he removed to Portsmouth, Rhode Island, and about a year later removed to Flushing, Long Island, but soon returned to Rhode Island. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the connection between Rhode Island and Barbados was extremely close. Many had brothers or kinsmen among the settlers at Barbados and there was a constant migration of families between the two places. Rhode Island exported timber, pipe staves, salt fish, cheese, horses (Narragansett) etc. to Barbados and imported from that island muscovado sugar and molasses. Shiploads of this molasses were made into New England rum.”

The shipping book of Walter Newbury, a Newport merchant, shows how frequent and prolific this trade was and the tremendous variety of goods. Newbury’s first shipment on November 18, 1673, was for Hope Borden to her husband, Joseph, who had moved from Portsmouth, Rhode Island to Barbados. Hope followed him to Barbados after the birth of their third child. Another example of the many Aquidneck-Barbados connections is the Rodman family, who appear in the same December 22, 1679 parish register in Christ Church, Barbados as Edward and some other Robinsons. Sarah Rodman owned 75 acres, John owned 7, John junior owned 47, and Richard owned 10. John Rodman’s will dated September 16, 1686, mentions sons Thomas (born 1640) and John junior (born 1655/6). Thomas was a surgeon, a Quaker, and was in Newport by 1675 where he married both Patience Easton and, later, Hannah Clarke. John junior was in Newport by 1682 and was also a surgeon. Land records regarding the sale of his plantation refer to him “now of the colony of Road Island, and Mary his wife,” as signed June 6, 1684 in Newport witnessed by Gov. William Coddington. John junior was also a Quaker minister and purchased a large tract of land on the South bluffs of Block Island, where Rodman’s Hollow bears his name today. Margaret Rathbun was a witness at his wedding on Block Island in 1705. It’s possible that the original Rodman on Barbados came as a 16 year old boy, “Thomas Reddman,” on the ship that left London in 1635 with many other young men “to be transported to the Barbadoes & St Christophers.”

G. Andrews Moriarity, who lived in Newport, traveled to Barbados to search records that he published in “Barbadian Notes” in The New England Historical & Genealogical Register (Vol 67) in 1913. He transcribed a gravestone that said “In Memory of Peleg, ye son of Job Almy of Tiverton in ye County of Bristol and Province of ye Massachusetts Bay in New England Esq. and of Bridget his wife, who died February ye 18, 1734 in ye 25 year of his age.” Bridget was the daughter of Gov Peleg Sanford and Mary Coddington. Moriarity also noted Newport resident Daniel Gould, whose mother was the daughter of John Coggeshall, leaving a will in Barbados on March 5, 1693/4. He noted the will of Newport resident Roger Goulding dated March 1 1694/5, and the will of John Redwood dated July 20, 1660 – a likely relation of the Newport Redwood family, whose history before Newport was in Antigua. Moriarity also found land records proving that Resolved White, a MAYFLOWER passenger living in Scituate, was in Barbados in March 1656/7 and in May 1657 with his wife Judith, who was the daughter of Barbadian William Vassall. Moriarity later noted a record dated “Newport on Road Island ye 18 November 1673” to Joseph Borden, Roger Goulding, Elisha Sanford, and Josiah Arnold in Barbados – it was an order to sell the ship JOANNA and SARAH, signed by Sarah Reape, Benedict Arnold, Sr, Caleb Carr, Peleg Sanford and Thomas Ward. Joseph Borden is yet another example of an Aquidneck Island resident moving to Barbados – in this case, from Portsmouth with his wife and children.

Barbados at The Beginning

Barbados was settled in 1627. Edward arrived in 1634 at the age of 18. The 1636 population of Barbados was only 6,000 whites, the majority of whom were indentured, and very few black slaves. The initial crop was tobacco, followed by cotton and indigo. Sugar wasn’t being produced at scale until around 1640, in concert with the increase of the black slave population. By 1684, the population was 23,624 whites and 46,502 black slaves. In 1634, Barbados had not yet began its dramatic transformation into a global sugar power. As Richard Ligon wrote,

“At the time we landed on this Island, which was in the beginning of September, 1647, we were informed, partly by those Planters we found there, and partly by our own observations, that the great work of Sugar-making, was but newly practiced by the inhabitants there…..But, the secrets of the work being not well understood, the Sugars they made were very inconsiderable, and little worth, for two or three years. But they finding their errors by their daily practice, began a little to mend; and, by new directions from Brazil, sometimes by strangers, and now and then by their own people…But about the time I left the Island, which was in 1650, they were much better’d; for then they had the skill to know when the Canes were ripe…“

Initially, acreage across Barbados was split between pasture, wood, crops and sustenance provisions such as corn, potatoes, plantains, cassava, pineapples, melons, bananas, guavas, watermelons, oranges, lemons and limes. By the time sugar took over the exports, nearly all land was used for growing sugarcane and the inhabitants imported virtually everything else.

Robinsons on Barbados

The first record of an “Edward Robinson” leaving England for the new world is on January 6, 1634 in London on a list of passengers “to be transported to St. Christophers and the Barbadoes” who had all taken oaths of allegiance, as was custom, to be allowed to “pass beyond the seas” of England. Edward is aged 18 and is with 102 other passengers – virtually all men, 73% of whom were under the age of 24, suggesting they were likely indentured servants. On subsequent pages of additional ships are passengers with the very common name of Robinson – David, William, Thomas, Jonathan and Leonard.

The Robinson name was abundant in colonial Barbados. William Duke’s 1743 publication, “Memoirs of the First Settlement of the Island of Barbados,” lists the names of inhabitants that possessed more then 10 acres of land in 1638. Thomas, Richard, and Jasper Robinson are on this list but Edward was obviously not as he would have been just a few years into his servitude. William Aspinwall of Boston on December 10, 1649 recorded a bill involving the ship HOPEWELL bound for Barbados, and the granting of attorney by merchant John Allen of Charlestown to Edward Hutchinson & Francis Robinson to receive “in Barbados all debts summes of money goods wares merchandise” for three merchants including Raph Woory, who also traded wtih Richard Smith. On August 5, 1650, he again recorded a transaction involving the ship EXPECTATION wherein Adam Winthrop “constituted Francis Robinson of Barbados Merchant his Attorney granting him power to aske leavie &c. ..also to sue implead & psecute & generally to do all things which himselfe could doe if present.” This record clearly shows a “Francis Robinson” on Barbados that is not found in other lists and, notably as seen below, Edward later names a son “Francis.”

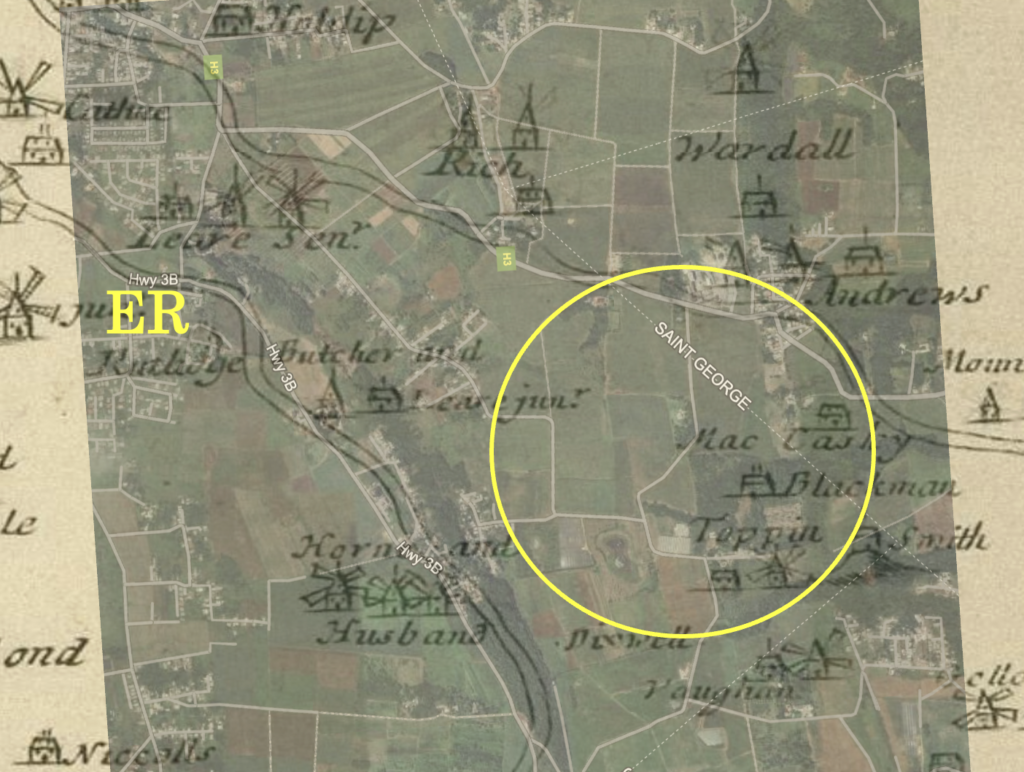

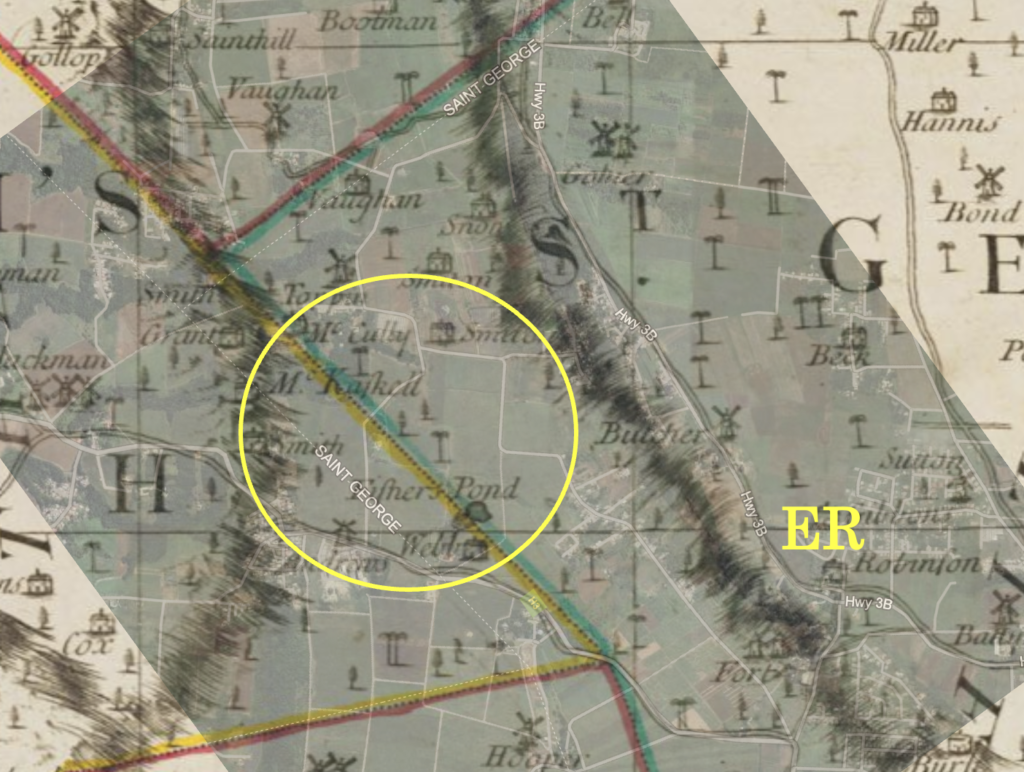

Robinsons show up with four distinct plantations in the Southwestern portion of the island that were large enough to be shown on the various maps: Christ Church by the sea on the border of St. Philip’s, St. Michael’s just East of present Bridgetown, St. George on the Western border with St. Michael’s, and St. George on the central North border. In a 1679 list of Barbados landowners, there are two Robinsons in St. Michaels (Richard, William), three in St. George (James, John, Joseph), and five in Christ Church (Thomas, Robert, Magnus, William, Edward). William’s plantation in St. Michael’s was the largest by far at 186 acres with two hired servants, 3 brought servants, and 76 “Negroes.“ The rest of the Robinson plantations were relatively minor affairs. Edward (at age 63) had just 7 acres in Christ Church, and neither servants nor slaves. The Robinson plantations are visible in the 1681 map (St. Michael’s, St. George) by Richard Ford, the 1722 map (with the addition of Christ Church) by William Mayo, the 1729 map by Herman Moll, and the 1752 map by Emanuel Bowen, which is pictured here.

Between Barbados & Newport

Barbados

As an indentured servant, Edward witnessed the extraordinary transition of the Barbados fields from tobacco to cotton, to indigo, and to sugarcane. His initial time on Barbados, however, was anything but a holiday. Before sugar and a large population of black slaves, when Edward served from 1634 until around 1641 (assuming a typical 7-year indenture), white servants were the majority of the field labor, and exclusively held the jobs off the field – miller, boiler, clayer, curer, distiller, driver, watchman, mechanic, cooper, carpenter, blacksmith, stone mason. At that time, and subsequently, servants and slaves were treated the same by the overseers and masters. During the indentured period, servants were disciplined severely, whipped, underfed, slept on dirt floors with huts built of forest vegetation, and had sparse clothing allowances. Punishments were brutal, executions frequent, and murders generally not prosecuted. Servants were also confined to the plantation and could not travel freely. Nearly half of servants aged 16-20 did not outlive their indenture, through overwork or disease (yellow fever, in particular). A period letter written from Barbados to London is indicative:

“August 3, 1688 – Sir Thomas Montgomery to Lords of Trade and Plantations. As Attorney General I am also a Justice of the Peace here….Thus much I think it my duty to lay before you. I beg also for your care for the poor white servants here, who are used with more barbarous cruelty than if in Algiers. Their bodies and souls are used as if hell commenced here and -only continued in the world to come.”

Yet Edward survived. It’s presently unknown what his “freedom due” payment was upon release from indenture, but for the early 1640s it was typically 10 pounds sterling or equivalent commodity. Perhaps his hard work and loyalty created the opportunity for a business relationship, with the recommendation of his former master opening commercial connections. Due to his relatively early arrival on the island and solidly ahead of the sugar boom, opportunities existed to become a small landowner that were not afforded to future generations of servants. Perhaps in his time on the plantation, Edward became involved in the merchandising side of the business. As said by Henry Drax, son of original settler Sir James Drax, in his Instructions For the Management of Drax Hall and the Irish Hope Plantations, “…have all Necessaries for the Estate bought by the Town Agent, therefore send to him on all Occasions for what you want; he will also ship and dispose of all my Sugars, which must be sent to him, and none sold at the Plantation..For paying for Provisions and all Workmen you may have Occasion to employ in the Plantations, my Town Agent will furnish you with Money. A particular exact Account must constantly be sent you by the Town Agent of all he receives from, and sends to the Plantations with the Prices of each Article, and of all other Particulars necessary to be known, and each Particular must be regularly entered in a Book to be kept at the Plantation for your Discharge, and as a Charge upon him.”

Edward’s career seems to have initially evolved into that of a “factor,” or agent, working on behalf of plantation owners and managing the pricing and sale of the plantation’s commodities, shipping logistics, financing, and supply chains. He was possibly a factor for the Toppin, Blackman or Andrews families, as discussed below. He also may have been a merchant trader, dealing in the goods and cargos between Newport and Barbados. Both of these would explain a constant presence between Newport and Barbados, with four round trips between the two places over his life.

Edward’s servitude was ending just as the first major sugarcane harvests were beginning. Edward would have seen the construction of the sugar works described by Richard Ligon (on Barbados from 1647-1650), and Edward may have been in the field when he was given his first rum:

“And as this drink is of great use, to cure and refresh the poor Negres, whome we ought to have a speciall care of, by the labor of whose hands, our profit is brought in; so it is helpfull to our Christian Servants too; for, when their spirits are exhausted, by their hard labor, and sewating in the Sun, ten hours every day, they find their stomacks debilitated, and much weakned in their vigour every way, a dram or two of this Spirit, is a great comfort and refreshing to them. This drink is also a commodity of good value in the Plantation; for we send it down to the Bridge, and there put it off tho those that retail it. Some they sell to Ships, and is transported into foraign parts, and drunk by the way. Some they sell to such Planters as have no Sugar works of their owne, yet drink excessively if it…They make weekly, as long as they work, of such a Plantation as this 30 lb sterling, besides what is drunk by their servants and slaves.”

Ligon said that “We are seldome drye or thirsty, unless we overheat our bodyes with extraorinary labor, or drinking strong drinks…or the drinke of the Island, which is made of the skimmings of the Coppers, that boyle the Sugar, which they call kill-Divell.” In addition to rum being distilled on plantations, molasses was shipped to New England where it was distilled into rum (as described in more detail on the Richard Smith and John Rathbun pages). The intricate process of distillation was described by Ligon. By claying sugar, Barbados planters extracted as much molasses as they could and, commensurately, distilled as much rum as they could to maximize their output. According to Henry Drax, “The Still-House if well taken Care of, brings very considerable Profit with little charge…I would have all my Rum sent to Town, and none sold at the Plantation…” But distillation didn’t consume all the molasses, and the surplus was a key export as well. Stills were certainly in operation in Newport as the sugar trade exploded in the 1640’s.

With servitude concluding at the beginning of 1641, Edward either continued working as a freeman in Barbados, perhaps amongst the merchants in Bridgetown, or for a Planter. Or perhaps he left immediately for Rhode Island, which he had certainly heard of on Barbados and where family connections may have existed.

Newport

Edward next appears, after an approximate 2,100 nautical mile voyage, in Rhode Island. On a rhumbline course at 7 knots, this would have taken about two weeks. He was in Rhode Island sometime prior to June 7, 1643, when the Rhode Island records on June 7, 1643 show him standing for accusations of trespassing by “Henry Bull of Nuport against Ed. Robinson of the same Towne.” This is the first record of an “Edward Robinson” in New England. Trespassing seems to have been a common offense in those days as the court records are full of cases. Henry Bull wasn’t just any colonist – he was a signer of the Portsmouth Compact, was part of the group that then formed Newport, and twice served as Governor in later years. This Newport trespassing record says Edward is a resident of Newport and disproves the “Edward” that appears, with no last name, under “Thomas Robinson” on the August 1643 list of men able to bear arms in Scituate, Massachusetts. The records are also a couple months apart and there’s little reason for someone to be trespassing 70 miles away from home, which would have taken a day of walking, and a ferry. Edward Robinson of Newport was unique. Prior to this time, there are no records of him in New England, nor does any “Edward Robinson” exist in ship logs to New England. Edward next appears in the Rhode Island records on January 7, 1644 for not paying Henry Bull the fine for his prior trespassing. The following year, on January 6, 1645, he is in court along with William & James Weeden and Nicholas Cotterell for owing money on the lands given to them by the town of Newport. Sometime between then and March 1645, he must have paid because “Ed. Robinson bound to his good behavr” had John Wood and Robert Griffin acting as his sureties. Why did he go to Rhode Island, of all available choices, after his indenture period? The answer was likely a family connection, or having witnessed the trade potential from the new sugar crop, or both. The Quaker connection between Barbados and Newport was also quite strong. He also may have heard that lands were available in the relatively new settlement on Aquidneck Island, and that trading land was the path to prosperity.

Barbados

Subsequent to the 1645 record, there are – inexplicably – no further Rhode Island records on Edward for 10 years. Having established a presence and land ownership in Rhode Island, he then likely traveled back to Barbados between late 1645 and early 1646. Whether he knew her before he originally left for Newport, or had a quick romance upon his return, Edward married Ann Bedford in Christ Church on January 14, 1647. Edward was 31 and had lived a more adventurous and busy life than many in those days who, comfortably in mainland cities and towns where they grew up, married younger. The Anglican church records show the birth of a daughter, Elizabeth (October 15, 1649), the unfortunate burial of a daughter, Bridgett (September 21, 1651; no birth record), and the birth of another daughter named Bridget (May 29, 1652). At this stage, we don’t know where Edward was living, but he had yet to appear as a landowner on Barbados – likely because he had not yet accumulated the capital to do so.

Newport

After these five years on Barbados, he sailed back to Newport sometime between 1652 and 1655. At the age of 39, he appears back in Newport on the 1655 list of 85 freemen. On February 23, 1658, he sold land lying between Newport and Portsmouth to Samuel Billing, witnessed by Richard Tew and James Barker.

Barbados

After the three years between these Rhode Island records, Edward doesn’t appear for eight years in the records of either Rhode Island or Barbados. During this time, Ann Bedford died and left no burial record. Research into colonial Barbados is difficult for many reasons, but particularly as noted in Duke’s Memoirs when “about the year 1666, the Bridge-Town was burnt and all the chief Records lost by a Hurricane, which happen’d the same year.” For this reason, the church records are most important. Edward was back in Barbados at the age of 50, where married his second wife, Christian, in 1666, before the birth of their first child together that year. Working backwards from names and dates given later in his will, over the 1666-1670 period, he fathered Edeth, Katherine, Christian, Rachel, and Edward (who was under the age of 21 in the will). As discussed below, his will names these children as well as his daughter, Bridget, that he had with Ann.

Newport

He next appears in Rhode Island at age 55 on the Grand Jury on the General Court of Trials in Newport on May 8, 1671, in the presence of Governor Benedict Arnold, John Clarke, John Cranston, John Coggeshall, and Roger Williams. He then appears on three more Grand Jury assignments in Newport: October 22, 1673, May 11, 1674, and May 10, 1675. Then, on May 8, 1676, he is at court himself for indebtedness to Capt. John Cranston.

Barbados

After these five years in Newport, sometime after 1676 Edward returned to Barbados where he appears on the December 22, 1679 list of landowners in Christ Church. This is the first record Edward’s land ownership on Barbados, the culmination of capital accumulation from his career following his indenture. It was a more difficult time on the island, and the primary sugar boom had passed. Now, sugar prices were falling along with profitability. Successful planters took more of the overall business in-house, playing the roll of factor, merchant, insurer and even shipper. Edward’s experience in the field, in the trade, and in Newport, were well-suited to this new environment. His Christ Church land today must look similar to the way it did then, as it contains the eastern end of the airport runway. Other “Robinson” owners in Christ Church include Thomas, Robert, Manuss, and William. “Robinson” owners on the St. George list include James, John, and Joseph. However, very shortly thereafter, on March 9, 1680, Edward is on the St. George militia roll of Col. Thomas Colleton, Capt. James Binney’s company. Miles Toppin, Bryan Blackman, Thomas Leare, Jonathan Vaughan, and William Smith are in the same company. Toppin was called a “friend” in Edward’s will and was a trustee, and land records show both Blackman and Toppin in St. George. As was the case throughout the Caribbean, Edward now likely owned multiple properties – his original 7 acres in Christ Church and now land St. George. As discussed below, his will was made in St. George so that was his primary residence, as he wouldn’t serve on the St. George militia while living in Christ Church. The fact that he had neither servants nor slaves in Christ Church suggests that he may have leased out the land.

The Barbados Archives show the following probate record that supports Edward’s move from Christ Church to St. George:

“Blackman, Bryan, St. George’s Parish, 25 June 1685, RB 6/10, p. 399, Son Francis Blackman – land joining Jonathon Andrews & Edward Robinson.”

Edward’s aforementioned militia record, and the trustees in his will, contain the names with contiguous lands in Moll’s adjacent map: Robinson, Andrews, Blackman and Toppin. While the name placements may seem distant, estate borders themselves often followed very strange paths (as I’ve learned walking the Pinney family’s lands on Nevis). Robinson’s crop land was below what is now Golden Ridge on Highway 3B, itself created by marriage between the Butcher and Leare families. There is still a “Fisherpond” road that corresponds to “Fisher’s Pond” on the map. Robinson’s land would have been to the East between Sweet Vale (formerly Sweet Bottom) and Redland Plantation, which is the former Toppin plantation. Sweet Vale and what is now Edward’s land is now home to the West Indies Central Sugar Cane Breeding Station, the only one in the Caribbean, and the land is known as the best, deepest and most fertile on the island. The location of Edward’s house on the ridge would have had a sweeping view of the valley and his lands were a very short distance away. While the Ford map only shows Edward with a house, it shows that his friend Miles Toppin also had a windmill, which likely ground Edward’s cane. Blackman and Andrews were both larger estates with multiple windmills.

Trouble in Paradise

Newport

Shortly after his appearance in the 1680 militia roll, business brought Edward back to Newport, where his life takes a dramatic turn. Despite the fact that his wife, Christian, is alive and well in Barbados, taking care of his several children, Edward has a moral transgression in Newport that likely takes place around 1681 when he is 65. Adultery was not taken lightly in the colonies, and the punishments in earlier years on Aquidneck Island included public whippings. Regardless, Edward was enamored with a married woman named Margaret Hall. She must have had some alluring qualities that let him overlook – or perhaps he did not know – the fact that Margaret had already taken her husband, James Hall, to court in 1674 perhaps in an attempt at divorce. James Hall’s father, John, was on the list of original Newport settlers in 1638 and the 1655 Freeman’s list. Margaret had also very recently, in 1679, had another child out of wedlock with John Albro junior, but the case was dropped as John’s father was one of the leading figures in the colony and was conflicted in his position on the General Court of Trials. So she certainly had a reputation. Margaret was far younger than Edward, and although he was at an advanced age, male fertility then, as now (Mick Jagger, aged 73), was certainly possible. Margaret, assuming she was around the same age as her legal husband, James Hall, was probably 38 at the time, working backwards from the fact that both Margaret and Edward were holding a child in their arms in court. They may have been twins. Whether or not Edward was physically attractive, he had wealth, standing, land in Newport, and land and business in Barbados – and Margaret had a clear a record of attracting (manipulating?) men. This event must have turned Edward’s world upside down. They may have hidden their relationship for a while as, on March 25, 1684, Edward was in court for trespassing on the land of John Parker, but for nothing else. However, on September 2, 1684, both Edward and Margaret were in court to account for their relationship:

“Edward Robinson of Newport being charged for haveing a Child or children by Margaret Hall the wife of James Hall, and appearing in Court with a child in his Armes Owned that he had had to doe with that sd woman, and Owned the Child to be his and Referred himselfe to the Judgment of the Bench. Margaret Hall also appearing in Court with a child in her armes owned the same. This Court takeing the premisses in Searious Consideration and for weighty matters presented before the Court doe see cause to leave the whole matter to the next General Asembly to be held the last Wensday in October next Ensuing at Warwick.”

The records for “October next Ensuing” do not exist. Edward shows up again in the Rhode Island land evidences on December 10, 1684:

“Edward Robyson of Newport Husbandman Margrett Hall the wife of James Hall in the said Island Have given the said Margrett (…after my decease) all my houses and Lands within the said Town on Consideration, that Margrett shall bring up Edward Robyson and Francis Robyson my two sons And after the decease of Margrett I do give to my sons al the afore-mentioned houses and Lands Equally to be divided I do give Margrett all my household stuff Redy mony Leasses Chattels at her decease to be my sonns tenth day of December 1684. Edward X Robyson his marke Wit. Edward Greenman, Elias Williams.”

He was still in Newport the next year on December 18, 1685 when he amended it so that either son should retain all the assets:

“If either of my sons shall decease then that part of my houses and lands shall be the Right of the surviver. Eighteen day of December on Thowsand six hundred Eighty five. Edward X Robyson his markee Wit. John Sanford, Stephen Brayton”

Two years later, either Margaret has died or her relationship with Edward has ended (she may have moved on, yet again, to someone else) because he put his sons (likely aged 4 years) under the care of three friends. Margaret’s husband, James Hall, likely had no interest in caring for children that were not his. On May 18, 1686 in the land evidences:

“Edward Robinson off Newport yeoman to my two Children Edward and Francis Robinson which I had by Margrett Hall and because they are under Age I have chosen as Feffees for my two Children, Edward Greenman, Clement Weaver senior and Thomas Burge off Newport Yeoman doe give in trust and on the behalfe of my said Children all that my manshion House and Land In the Towneship of Newport about fourty acres bounded Northerly by the Land of Jno: Parker & John Allen, Easterly by the common Southerly by the Land of John Wood and Westerly by the common or highway the same shall be the Estate of my two sons and the surviver of them if any one dyes before the Other Comes to the age of Twenty one yeares…Eighteenth day of may 1686. The marke of Edward X Robenson. Wit. John Hulme, the marke of John X Benett. Edward Robenson..acknowledged above, Walter Clarke Govr.”

Edward chooses respectable citizens and landowners to look after his sons – Edward Greenman and Clement Weaver. Thomas Burge (Burgess) was a relative latecomer to Aquidneck, arriving in 1661, and had been whipped in Sandwich, Massachusetts for adultery and divorced by his wife that year. Perhaps these circumstances made Edward sympathetic to him. This record is Edward’s last appearance in Rhode Island.

Notably, it is not a will, but a land evidence. There are no death, burial or probate records for an “Edward Robinson” in Newport or the wider Rhode Island and adjacent Massachusetts area at this time. This is the last record of Edward in Rhode Island.

The birth of sons in Newport was certainly not part of his plans and whatever distance separated Newport and Barbados, it appears that he decided, at age 70, to permanently set up the sons he hadn’t planned on having and to return home to Barbados. His wife, Christian, may or may not have welcomed him, depending on what she knew. With the constant traffic between Newport and Barbados, it seems highly improbable that she didn’t know, and Edward would certainly have had to explain what was to happen with his Newport assets.

Final Voyage

Barbados

After around four years in Newport, Edward likely left in 1686 immediately after the custody and land transaction for his children. He returned to his planation in St. George. He next appears in the Barbados records in 1690 for his will, an abstract of which shows:

“Robinson, Edward, planter. St George’s Parish, 10 June 1690. My son Edward Robinson at 21; my daus Bridgett Robinson, Edeth Robinson, Katherine Robinson, Christian Robinson, and Rachael Robinson; my wf Christian Robinson – Xtrx; friends Capt. Miles Toppin and John Marshall – Trustees. Signed Edward (X) Robinson. Wit: John Bird, Christopher Simpson, John (X) Kilderine, John (X) Kaind, Abraham (X) Peoans (court names Abraham Scoans). Proved 14 July 1690” (RB 6/41, p. 317)

Both trustees, Miles Toppin and John Marshall, are on the December 23, 1679 list of St. George landowners. We know that this will abstract is the same “Edward” because of the presence of Bridget from his first wife, Ann Bedford, and the births of all the children were recorded in Christ Church. That Edward signs with a mark also matches his signing with a mark in the Newport records. There are no burial records of an “Edward” in Barbados that are reasonably close to the date his will was proved – but his churchgoing may have stopped as a result of his adultery. That he referred in his will to his “friends” with that specific word suggests that he may have been a Quaker as the Society of Friends had very strong links between Barbados and Newport, Rhode Island and, in particular, with many commercial leaders. This might also explain a simple burial with no surviving headstone.

Edward led an extraordinary life, leaving England when still, essentially, a boy and heading out to a very different world – and carving out his own complicated, and human, place in it – from servant to landed planter.

Afterwards

His Rhode Island children, Francis & Edward, eventually sold their Newport properties and went westward where Henry Hall, brother of their mother’s legal husband, was a purchaser and founder of Westerly, Rhode Island in 1664 out of the inhabitants of Misquamicut and Pawcatuck. The boys were likely ignored by James Hall but perhaps Henry took sympathy on them, although he does not name them in his will. The Western land would have represented new opportunity for Francis & Edward, purchased with the proceeds of Newport assets, and also represented a new life away from the closed world of Newport where they had no immediate family, and where they were certainly known to have been born out of wedlock. Since Edward left when they were four years old, and died when they were just eight years old, they had to find their own way in the world – and like the history of America, it involved moving West away from the initial settlements.

Francis shows up in many land transactions in Westerly and bordering Stonington, Connecticut. Francis and his wife, Elizabeth, named a son “Edward.” The name “Francis Robinson” is uncommon in early New England, but there are many, many “Francis Robinson” deaths in England before 1675. While Edward fathered many daughters, he only had three sons – Edward in Barbados, and Francis & Edward in Newport, suggesting the likely name of his own father, at present unknown. Edward’s choice of Bridget for the name of his first Barbados daughter is intriguing. Bridget was a relatively uncommon name in early New England, but it was prolific on Barbados. The first and most obvious “Robinson” connection to New England is John Robinson, pastor to the pilgrims. He did not sail on the MAYFLOWER, nor did his wife, Bridget White, although her sister did. Bridget had a brother named Edward and a sister named Frances.

Edward is not immediately related to the other well-known Robinson family in Rhode Island – that of Rowland Robinson, who came relatively late in 1675 and lived in Narragansett, where his family was heavily invested in the Caribbean trade. Edward possibly came from Leicestershire, where numerous records can be found for men named both Edward and Francis Robinson.