Amos Rathbun

1738-1817

Amos Rathbun was born in Stonington, Connecticut on Jan 26, 1738. The French & Indian War brought him, at the age of 19, deep into the woods of upstate New York and he eventually moved to the Berkshires around 1765, settling in Richmond, Massachusetts, where he was a farmer and operated a mill. He served extensively in the Revolution as a captain of militia from Richmond and, after the war, he joined the Hancock, Massachusetts Shaker Society – without his wife – where he became a teaching elder and remained a member until his death on July 24, 1817.

Stonington, Connecticut

Amos was the great grandson of John Rathbun, who still spelled the name “Rathbone” and was one of the original 1661 purchasers and settlers of Block Island, Rhode Island. John’s name is inscribed on Settlers Rock at the north end of the island in Cow Cove, the site of the original settlers’ landing in the spring of 1662. Amos’ father, Joshua, migrated off Block around 1724, likely due to an increasing population, increasingly related. A short 20 nautical mile sail brought the family to Stonington. Joshua was a co-founder of the Baptist church in Stonington in 1743, the second in Connecticut. Joshua operated a windmill to make cloth and grind corn and grain. These trades were taken up by Amos and two of his brothers, Valentine and Daniel, and the mill was in operation late into the 1700’s. Evidence of the mill is found in the records of Joshua Hempstead, who recorded on February 11, 1752, “I brot my blue cloth dere to Rathbon’s fulling mill.” The diary of Thomas Hazard of South Kingston also references the Rathbun family mill: “Nov 6, 1781 – went to Rathbon’s Mill. Dec 23, 1782 – I carried corn to Rathbone’s mill. July 1, 1783 – Went to Rothbone’s mill for a grist of wheat.”

French & Indian War

At the age of 19, Amos was among the Connecticut troops raised for the relief of Fort William Henry, which was besieged by the French in August 1757 under the Marquis de Montcalm. Amos is seen in a record dated August 9, 1757 under Capt. George Holmes as part of twenty men “for his Majesties Service & Relief of the fort Now Beseiged.” He appears again in Col. Jonathan Trumbull’s 12th Regiment under Capt. Daniel Cone from August 9-24 “for their Service at the time of Alarm for Relief of Fort Wm Henry and Places Adjacent.” The relief forces, comprised of New England and New York militia, arrived at Fort Edward between August 10-15. Due to the 200 mile march, they did not arrive until after Fort William Henry had surrendered. The defeated Colonel George Monro left Fort William Henry and arrived at Fort Edward on August 15 after suffering in the march depicted so well in the 1992 film adaptation of James Fenimore Cooper’s “The Last of the Mohicans.” General Webb dispatched curriers to turn back any supporting militia still on the way to Fort Edward.

The Berkshires

Amos returned to Stonington and married Martha Robinson, who lived nearby in Hopkinton, Rhode Island, on September 28, 1761. The families were undoubtedly close as Martha’s brother, Edward, married Amos’ sister, Susannah. Sometime after, Amos moved to Berkshire County, Massachusetts, continuing a pattern of many families from southern Connecticut (including the Rossiter family from Stonington), where land was more plentiful as he’d seen on his earlier march through the Berkshires in 1757. In the Berkshires, Amos lived as a farmer in the “Northeast District” close to the Pittsfield Line according to the Richmond Historical Society and the Knurow Collection in the Pittsfield library. Today, this land is in the town of Richmond and is squeezed tightly between the borders of Pittsfield, Richmond and Lenox, to the East of Barker Road and Swamp Road and to the South of Tamarack Road. A 1794 map shows “Rathbones Pond” which is, today, called Mud Pond.

Amos was granted land in Richmond on October 2, 1770 (land evidence book No. 8, page 242) and also owned Lot 47 “west upon Richmond Pond, north up Pittsfield Co. line, east partly upon heir of Daniel Burdick deceased, with partly upon a road and partly upon Amos Rathbun 100 acres (whole of Parks lot) with the house & barn.” Amos sold land “for the use of a burying place for them” now called Northeast Burying Ground on Cemetery Rd, just south of Mud Pond and northeast of Richmond Pond. A sign at the entrance to the cemetery notes the oldest graves belong to ancestors Zeuriah Collins and her husband Joseph Chidsey – who was a taverner, and his son, Augustus Chidsey, married Amos and Martha’s daughter, Anna Rathbun. On April 6, 1789, on the Shaker Road, there is a record of Amos engaging to “make a good & sufficient bridge over the brook which crosses the new road.” Amos’ oldest brother, Valentine Rathbun, also left Stonington for the Berkshires around 1769, settling in Pittsfield nearby Amos and brother Daniel in Richmond. Valentine’s land was near Richmond Pond “with the right of flowing as much more land as should be necessary to raise a fund of water sufficient for a fulling mill already built and a sawmill to be built.” In 1767, he was assigned church pew No. 27 in the Richmond Congregational Church; the church exists today on the same site, but the original building burned in 1882.

Revolutionary War

The Berkshires were at the crossroads of many events during the Revolution. When sentiments for revolution began to escalate, Amos also found himself living near, and interacting with, outspoken Berkshire colonists on the patriot side like David Rossiter, Benjamin Simonds, John Brown, and John Stark. His family had been in America for some time, and he’d fought in the prior war to keep the new colonies from speaking French. While it is clear that Amos chose the patriot side, as his participation in the war is well documented through muster rolls and records, what is less immediately clear is precisely what he did and saw during his service. Fortunately, a broader story emerges from the Revolutionary War pension applications of men that served under Amos. His service is unique in scope, in part because of the Berkshires location, and in part by his willingness to participate. In the wider British strategy of closing off New England by converging three columns on Albany, Amos was impacted by the strategies of all three British generals: John Burgoyne, William Howe, and Barry St. Leger. The names of the places he served ring loudly in the history and critical turning points of the Revolution: Ticonderoga, Bennington, Saratoga, New York City, White Plains.

The 2nd Berkshire Regiment of Militia was formed August 30, 1775 under Col. Benjamin Simonds. Under Simonds were Liet. Col. Jonathan Smith, 1st Major David Rossiter, and 2nd Major Caleb Hyde. In January 1776, a new act was passed, and John Fellows was made Brigadier General for Berkshire County, and the prior appointments were repeated. Simonds was important to Amos’s service, as their sphere of the world was quite small. Simonds was captured at Fort Massachusetts, in present day Williamstown, in August 1746 and taken to Quebec. Later, during the last French & Indian War, Simonds was a private under Captain Ephraim Williams (for whom Williams College is named) from October 1754 to March 1755. He returned to settle in Williamstown where his house still stands. Amos was Captain of the Second Company.

Ticonderoga Winter 1775-1776

This was an active time in the history of Ticonderoga, the key strategic location between New York City and Canada. In May 1775, Ticonderoga was captured from the British by Ethan Allen and his Green Mountain Boys. With this came 59 cannon that were famously retrieved by Col. Henry Knox in harsh winter conditions and dragged all the way to Boston, allowing Washington to dislodge the British. Knox first went to New York City, where his diary entry on November 27, 1775 says “glad to be leaving N York it being very expensive.” The diary has entries in the same ink and style in a list at Ticonderoga from December 9 though the 11th. By the 15th, he appears to have left when he “paid Lieut Brown for Capt Johnson which he paid the Carters for the use of their Cattle in dragging Cannon from Ticonderoga to the North Landing of Lake George” and on the 16th when he “paid the battoe men for going up to Ticonderoga & bringing [ ] concerning the cannon.” It’s a 114 mile march from Pittsfield to Ticonderoga, or just over 3 days marching 12 hours a day, so Knox and the cannon were gone by the time Amos arrived. Amos would not have passed the caravan either since he went up on the east side of the Hudson while Knox came down on the west, as his diary describes, through Saratoga and crossed at Kinderhook.

Amos had traveled as far as the southern end of Lake George, to Fort William Henry, in the French & Indian War. Another fort was at the same location – Fort George – built in 1755, and is what Knox mentions in the diary above. Amos’ experience must have certainly lead to his being selected to command a company during the Revolution and, in particular, his familiarity with this part of the country. The presence of Amos at Ticonderoga this winter is seen clearly in the pension applications:

Amos Root – (who was later married by Amos) –“This deponent served the army of The Revolution as a levy on the 15th day of December 1775 under Capt. Amos Rathbone of the town of Richmond Massachusetts Col. Simonds Regiment and marched to Ticonderoga and deponent was stationed at what was then called The French Line about half a mile west of the fort at Ticonderoga and continued in that service for a period of three months.”

Thomas Kellogg – “that in or about the month of December 1775 he enlisted in the said town of Pittsfield under Capt. Amos Rathbun (Col. and Regiment not recollected) in General Ware’s Brigade in the Massachusetts line and he was stated at Ticonderoga, and served three months, was there discharged and returned home to Pittsfield.”

Asahel Stiles – “This deponent enlisted in the army of the Revolution as a levy on the 15th day of December 1775 under Capt. Amos Rathbone of the town of Richmond Massachusetts. Col. Simonds Regt and marched to Ticonderoga and deponent was stationed at what was then called the French Line about half a mile west of the fort at Ticonderoga and continued in that service for a period of three month.”

The time spent in the fort, like that for any winter soldier, was likely extraordinarily cold and hard, with short supplies and inadequate – even destitute – clothing. Amos was stationed on the old French Lines, which means he was outside the comforting walls of the fort itself. Shelters were made in small log or board huts dug into the earth. Men weren’t lying around in bed, however. There was constant activity for firewood, Ticonderoga improvements, drilling, guarding and scouting.

Fort Edward & Fort George 1776

In May 1776, Amos was made Captain of the 6th company in Col. Benjamin Simonds’s (2nd Berkshire Co.) regiment of Massachusetts militia.

Joseph Rowley – “That he again entered the service as a volunteer under Colonel Ashley and Captain Rathburn and marched from Berkshire aforesaid to Albany and from thence to Fort Edward and remained there as the general place of rendezvous nearly all the Summer. That he went into the service at this time in the latter part of May or the first of June 1776, that he spent some time at Fort George that his principal duty was hunting Tories and Indians in small scouting parties, that he remained in the service at this time about three months having left the same the latter part of August 1776 that he was then discharged from his service and returned home.”

Fort Edward stood where the Hudson River became unnavigable and required a portage to Lake Champlain. It was one of many forts, including Ticonderoga, that helped control the water route from Canada to New York City. Next to the Fort is Rogers Island, on which Robert Rogers wrote his rules of rangers in 1757. Fort George, which no longer exists, was essentially a hospital fort nearby where Fort William Henry stood at the southern end of Lake George. During this period of 1776, not a lot was happening nearby and life, as Rowley mentions above, was likely consumed by drilling and scouting. It’s notable, however, that Benedict Arnold was at Fort Edward during this time, well in advance of both his heroics at Saratoga and his treason in 1779. From Fort Edward, on June 24, 1776, Arnold wrote to Col. Peter Ganesvoort: “A kinsman of mine will be at Fort George tomorrow in his way from Ticonderoga for Albany with a Pouch Goods to be made up for the use of the Army. You will please assist him in getting the goods forward – I oblige.” As a relatively small fort, it’s likely that Amos was in the presence of Arnold. At that point, Arnold had just captured Ticonderoga with Ethan Allen, and he had led a December 1775 expedition to Quebec to rally patriot support, only to suffer a significant leg wound during a battle there. Arnold would then help organize and lead the construction of a fleet to fight in the battle of Lake Champlain that October. Amos, however, was long departed. There was no rest for him, or many of his men, upon return from the Forts: he had to march immediately to New York City.

White Plains 1776

The battle of White Plains was the dramatic end of the larger battle of Long Island and New York City, which had brought in American troops from all over the east coast. The White Plains action, by giving the British pause, ultimately afforded Washington the ability to escape across the Hudson River to the west. We first see Amos in New York in the pension application of Moses Bartlett, who was in Amos’s company as part of Col. Jonathan Smith’s regiment:

Moses Bartlett – “That on or about the month of August 1776 he volunteered as a substitute for a man whose name he thinks was William Beard, in the company commanded by Captain Rathbone of Lenox in the Regiment commanded by Colonel Jonathan Smith of Lanesborough: that he marched in said company directly to New York City: was in the City when the British vessels Phoenix & Rose were returning from a trip up the North river – was in the battery when the topsail of one of these was shot away; and when this applicant lay in said company near Hellgate, his place was taken by the man for whom he was a substitute, this applicant having been with the army three weeks.” (Bartlett’s placing Amos from Lenox is appropriate since the actual Rathbun land in Richmond bordered Lenox and was a mile down present-day Swamp Road from, as of 2021, Bartlett’s Orchard.)

The ships PHOENIX (40 guns) and ROSE (20 guns) had been sailing from New York Bay up the Hudson (what Bartlett and others called the “North River”) and engaging American ships. On the night of August 16, 1776, they were attacked by American fireships but escaped and sailed downriver. On the morning of August 18 they had to run the American batteries, which fired continuously with the ships returning fire, as recounted in the “Memoirs of Major-General William Heath – by Himself“: “18th. – Very early in the morning, the wind being pretty fresh, and it being very rainy, the ships and tenders which were up the river got under sail and ran down, keeping as close under the east bank as they could, in passing our works. They were, however, briskly cannonaded at Fort Washington and the works below: were several times struck, but received no material damage. They joined their fleet near Staten-Island.”

Bartlett, therefore, had to have been in New York before the August 18 ship engagement, implying they left the Berkshires in early-to-mid August, which was around 40 hours away, or 3 days of 12-hour marching. John Ells recalls in his pension the route he marched in Capt. Root’s company of Col Smith’s regiment: “I resided at Lanesborough…I marched from thence to Pittsfield Mass where the company was embodied, marched from that place through Stockbridge, Sheffield, Salisbury, Sharon, Dover, Nine Partners and Kings Bridge to New York City where I remained about one month during which time the British fleet came into New York and we retreated to Kings Bridge and from thence to White Plains N.Y. The British ships came up the Est River and endeavored to cut off our retreat. We lay entrenched some time at White Plains until the latter part of September [October] when we had a battle at that place in which I was engaged. General Washington commanded at White Plains. After the Battle I marched to Croton Bridge New York where I was discharged.”

Things were heating up in the larger theater of New York when Amos arrived and, most importantly, the British fleet was assembling in New York harbor. British ships had been arriving since June. On July 3, Heath recorded that “The British troops landed on Staten-Island.” On August 1, “About 30 sail of British ships arrived at the Hook”, on the 9th “It was learnt that the British were preparing for an attack, and were putting their heavy artillery, &c. On board ship”, on the 12th “In the afternoon, 30 or 40 British vessels came through the Narrows, and joined the fleet” and on the 13th “A number more of ships, some of them very large, came in and joined the fleet.” On the 19th, he wrote “It was made pretty certain, that the British were upon the point of making an attack somewhere…On this morning, however, they landed, near Gravesend Bay, on Long-Island, about 8000 men.” And so it began.

Skirmishes were happening by August 24. Notable from a strategic standpoint, on August 27, the British sent three ships to Throgs Neck – recorded by Heath and then called “Frogs Point” or “Frogs Neck” – and landed men on City Island to potentially cut off retreat by the Americans out of the city and into Westchester County and Long Island Sound. This is also the day that the fighting seriously intensified on Long Island. The Americans evacuated Long Island the night of August 29. By August 31, the situation in the greater New York City area was becoming very tense and Washington issued the following General Orders:

The following disposition is made of the several Regiments, so as to form Brigades, under the commanding officers respectively mentioned. Gen: [John] Fellows: [Jonathan] Holman, [Simeon] Cary, [Jonathan] Smith. The General hopes the several officers, both superior and inferior, will now exert themselves, and gloriously determine to conquer, or die—From the justice of our cause—the situation of the harbour, and the bravery of her sons, America can only expect success—Now is the time for every man to exert himself, and make our Country glorious, or it will become contemptable. [General Orders, George Washington, August 31, 1776]

No official records or muster rolls exist for Amos or his regiment because, in “Weekly Returns of the Regiments of Horse and Foot, under the immediate command of His Excellency George Washington, Harlem Heights, October 5, 1776”, it was said of the Massachusetts Militia “computed at four thousand, so scattered and ignorant of the forms of Returns that none can be got.” Regardless, many other pensions for men that served with Amos, either in the original troops or subsequent reinforcements or related companies, align to these events:

Jonathan Tarbill – “from Richmond in the County of Berkshire in the State of Massachusetts, she remembers that he served under or in connection with one Captain Rathbone and Colonel Rowley….Her husband served as a paymaster in the Massachusetts Sate Troops or line or in some similar capacity because he had in his possession at sundry times large sums of money wherewith to pay off the Mass. State troops at White Plains New York and elsewhere to said troops belonged to the Massachusetts levies or line or Continental establishment. He served under or in connection with Captain Rathbone and Colonel Rowley.”

Amos Root – “The aforesaid Amos Root entered the same company and Regiment and served the same length of service and was discharged on the 15th of March 1776 and then returned to Pittsfield. Deponent believes the same Root served at another period where the army was at White Plains but cannot identify him in any company. Deponent further states that the same Amos Root was married in Pittsfield Mass to Anna Barker. Deponent was married June 17, 1784 by Elder Rathbone of Pittsfield.”

Joseph Chapin – “that in the month of August of the aforesaid year [1776] at said Tyringham where he then resided he volunteered in a company of militia commanded by Captain George King of Gt Barrington for the time of three months that he marched in said company to Norwalk Connecticut from thence to Valentine Hill so called in the State of New York and there joined the Regiment commanded by Colonel Simonds of Williamstown. From Valentine Hill, he marched in said company & regiment to White Plains and there joined the army under General Washington – that he was then assisted in building a breastwork that he was there at the Battle – that the army under Gen. Washington left the Plains and took their station on three small hills adjoining said Plains – the next morning White Plains were burnt, the enemy then moved up. Gen. Washington opened his batteries and continued cannonading the quarter part of the day – the Enemy then retreated back to New York. From thence he marched to North Castle. That he continued to serve in said company and regiment during the term of three months and four days. That the company remained four days by the special request of General Washington. That he was then discharged at said North Castle with the company. Colonels Ashley, Simonds and Maj. Jackson commanded the Regiments in which I served. I saw Gen. Washington, Lincoln, Lee & Lord Sterling at White Plains. Gen. Gates commanded at Stillwater & Saratoga.”

Not everyone from Berkshire county was in New York by August. Nathaniel Cowles pension states that “At Sheffield in the State of Massachusetts on the 17 of September, 1776, he enlisted in Captain Enoch Nobles Company in Colonel Benjamin Simonds Regiment for the term of two months and was marched to Kingsbridge and there joined the army under General Washington. Was ordered back to Valentine Hill and the next day marched to W[ ] and was there under arms for two days and then ordered to White Plains and there encamped. Soon after engaged in the Battle of White Plains, and after the British returned to New York, the army moved up the River, and when his time expired he went home and was discharged.” Ebenezer Phelps – “about the last of August or first of September AD 1776 at the town of Richmond in the County of Berkshire in the State of Massachusetts he entered the service of the United States in the company of Militia commanded by Captain Hughs, as he believes, Lieutenant Colt in the Regiment commanded by Col Simonds as he believes, that he marched with said company to the White Plains in the State of New York near where he was discharged in the month of November thereafter, having served about the term of two months.”

Kingsbridge was, literally, a bridge from the northern tip of Manhattan into the Bronx. Valentine’s Hill was to the North, in Yonkers, which today’s motorists will pass on the Cross County Parkway just as it meets the Saw Mill Parkway – the open land is now a seminary, appropriately located on Valentine Street. After driving the Americans off of Long Island, the British landed on Manhattan on September 15, after which there was a period of relative inactivity. According to Heath’s diary, on October 7, Gen. Benjamin Lincoln came to camp from Massachusetts with a body of militia. This was the first of his joining the main army. Several more of his regiments arrive on October 11, two of which were posted on the Hudson. Things changed dramatically on October 12, when 90 British boats full of men sailed from what is now called Randall’s Island into Long Island Sound and landed at Throgs Neck and advanced toward the edge of Westchester County in Pelham and then almost to New Rochelle. George Washington inspected the positions. By October 20, the Americans knew that “The White Plains” were their next position. The next night, Washington spent the night on Valentine’s Hill where Lincoln was quartered. The advance party reached Chatterton’s Hill at four in the morning on October 22, when they noticed flashes in the distance – which were actually the side expedition against Robert Rogers and his Queen’s Rangers in Mamaroneck. Heath says that, on October 22, “there were some strong works thrown up on the plain, across the road, and still to the right of it. Chatterton’s Hill was a little advanced of the line, and separated from it by the little rivulet Bronx.” Washington and Gen. Lee were surveying the position when the British army arrived and directed their first attack on Chatterton’s Hill.

The presence of Col. Benjamin Simonds and the Massachusetts militia at White Plains also receives mentions in several books. “Col. Benjamin Simonds regiment of Berkshire Boys, organized in 1775, was called out to meet the British in the fatal Battle of White Plains.” “Colonel Simonds with his regiment from Berkshire was in the unfortunate battle of White Plains, which was fought on October 28.” “During the military operations in Westchester County, after the retreat from Long Island in the Fall of 1776, Col. Simonds of Williamstown led a corps of levies from the three Berkshire regiments to re-enforce the army of Washington. Of this regiment, which served from the 30th of September…Rev. Thomas Allen was chaplain, and Pittsfield also contributed Liet. William Barber and fifteen men to its ranks. We know nothing of its service there except what is contained in the following extract from Mr. Allen’s diary, regarding the battle of White Plains and the few days immediately preceding it.”

The two Massachusetts militia were divided, with that of Col. John Brooks, of Reading, positioned on Chatterton Hill, and that of Simonds Berkshire militia on the adjacent Purdy Hill, which was the location of Washington. Wrote Thomas Allen of the engagement:

“Monday, Oct. 28. – About nine o’clock, A.M., the enemy and our outparties were engaged. About ten, they appeared in plain sight, filing off in columns to the left and towards our right wing, but no additional force of ours was as yet directed that way. At length, the enemy came up with our right wing, and a most furious engagement ensued, by cannonade and small arms, which lasted towards two hours. Our wing was situated on a hill, and consisted of, perhaps, something more than one brigade of Maryland forces. The cannonade and small arms played most furiously, without cessation; I judged more than twenty cannon a minute. At length, a re-enforcement of Gen. Bell’s brigade was ordered from an adjacent hill, where I was. I had an inclination to go with them to the hill where the conflict was raging, that I might more distinctly see the battle, and perhaps contribute my mite to our success. Just as we begun to ascend the hill, we found our men had given away, and were coming off the hill in some confusion, at which moment elevated shot from the enemy’s camp came into the valley, where we were, very thickly, one of which took off the fore part of a man’s foot about three rods from me, of which I had a distinct view, as would be supposed. I saw the ball strike and the man fall; and, as none appeared for his help, I desired five or six of those who had been in battle to carry him off. Others I saw carrying off wounded in different parts; and, with the rest, I retreated again to the main body on the hill, which was fortified, from which I had just before descended. Our men fought with great bravery; they generally, one with another, shot seven cartridges before they were ordered to retreat. They were sore galled by the enemy’s field-pieces. Our loss in killed, wounded, and missing, from the best information I can obtain, is about two hundred.”

Another detailed description of the battle exists in “Westchester County, New York During the American Revolution“:

“…The Massachusetts Militia, then serving with the Army, was to be formed into a division to be commanded by Major General Lincoln.” “General Heath’s Division was posted in a line extending from Fort Independence to Valentine’s hill. It is said, also, that a line of entrenched encampments was also formed, along the high grounds, on the western side of the Bronx river, from Valentine’s hill, on the South, to Chatterton’s hill, opposite the White Plains on the North; but by which of the Regiments they were constructed and by whom occupied, we are unable to state with certainty, although we suspect that the Massachusetts Militia, commanded by General Lincoln, and the two Brigades of General Spencer’s Division, commanded, respectively, by Generals Fellows and Wadsworth, who had been moved from the Heights of Harlem to Kingsbridge, on the 17th of October, were the artificers who constructed and the soldiers who occupied that very greatly important line of hastily constructed earthworks.” (261) “On the western bank of the Bronx river, which flowed through a marshy valley of some extent at its base, arose the bold and rocky height which was known then, and is still known, as Chatterton’s hill. It is one of the range of high grounds on the western side of the Bronx on which the line of entrenched encampments had been thrown up by detachments from the American Army. It had been occupied, and an earthwork of small pretensions had been thrown up, on it, probably by the Regiment of Massachusetts Militia, commanded by Colonel John Brooks, then of General Lincoln’s Division.” “…a portion of General Lincoln’s Division, with all of that of General Spencer, had been detached from the main body of the Army, and sent forward, with orders to occupy all the high grounds between Valentine’s Hill and The White Plains, and to strengthen them with entrenchments; and because the Regiment commanded by Col. Brooks formed a portion of one of the Divisions who were thus detailed to occupy and strengthen those high grounds; and because we have not found the slightest allusion to the Regiment commanded by Col Brooks in any of the descriptions of the movement of troops, at any time previous to the attack on Chatterton’s hill by the Royal troops; and because we cannot find any Order from Head-quarters, for any other occupation of Chatterton’s hill, until the morning of the 28th of October, when Col Haslet, with his well-tried command, was ordered by General Washington “to take possession of the hill beyond our lines” “and the command of the Militia Regiment there posted” (Colonel Haslet to General Rodney, November 12, 1776) when a Regiment of Militia whose subsequent conduct clearly identified it as that commanded by Colonel Brooks, was found in possession of the ground.” “the line was formed, with the Regiment of Massachusetts Militia, commanded by Colonel Brooks, sheltered by a stone wall, and supported by the Regiment of Marylanders commanded by Col Smallwood…on the extreme right – the latter, the remains of that fine body of Maccaronies so called by the New Englanders, whose gallant conduct at the Battle of Long Island had won the admiration and sorrow of General Washington. On the left of the Marylanders was posted the Delaware Regiment…whom Col. Haslet commanded. With the exception of the Regiment commanded by Col Brooks, no portion of that force was composed of Militia; all, except that Regiment, were Continental troops.”

As the British approached, Capt. William Hull, present on Chatterton’s Hill, observed of the army that:

“It’s appearance was truly magnificent. A bright autumnal sun shed its full lustre on their polished arms and the rich array of dress and military equipage gave an imposing grandeur to the scene, as they advanced, in all the pomp and circumstances of War, to give us battle.”

“General Howe determined to dislodge the Americans who had occupied Chatterton’s hill before he proceeded further in his movement against the main body of the American Army….With that purpose in view, the main body of the Royal Army was ordered to rest on its arms, on the Plain, within a mile and in open sight from the American lines; orders were issued for a Battalion of Hessians to pass over the Bronx river, supported by the 2nd Brigade of British troops composed of the 5th, 28th, 35th and 49th Regiments of Foot, commanded by Brigadier-general Leslie, and Col. Rall was ordered to move the Bridage he commanded on a charge on the right of the Americans simultaneously with the movement of the Hessian on their front.”

“On the portion of the American line that was exposed to that assault on its front as well as to the movement of the Hessian Brigade who had been ordered to charge on its right flank, simultaneously with the movement on its front, were posted the Regiment of Massachusetts Militia commanded by Col. Brooks, sheltered behind a stone wall and supported by the remains of the Maryland Regiment commanded by Col. Smallwood; and, against these, the two assaulting parties simultaneously directed their overwhelming power. There was no artillery to hurl destruction on either of the assailants since, by that time, the Delaware Reg, immediately on their left, was confronted by the 5th and 49th regiments who had crossed the river and were climbing the hillside..two well disciplined, well armed, well commanded British Regiments, besides the Hessian forlorn-hope on their front and three equally well-disciplined, well-armed and well-commanded Hessian Regiments on their right flank. It is recorded that the Regiment of Militia, commanded by Col. Brooks, notwithstanding the shelter afforded by the stone well, ‘fled in confusion without more than a random, scattering fire” (Col. Haslet to Gen Rodney, Nov 12, 1776). But the retreat of the Militia, to whom appears to have been assigned the part of holding Col Rall in check….the conflict was too unequal to be long-sustained and…with such great odds against the Americans…the regiments were compelled to give way…but the opposing forces were so unequal in their strength that a successful occupation of the hill could not have been expected, by any one – indeed, the fact that the entire detachment was not cut off from the main body of the Army, and captured by the enemy, reflects the highest honor on those who occupied the hill.”

With Amos and his men discharged in November, it was not long after they marched home from the scene of White Plains that they were sent once again for a winter at Ticonderoga.

Ticonderoga Winter 1776-1777

Amos returned from White Plains and, just two months later, on 16 Dec 1776, he was made Captain of the 2nd Company of a detachment, under Col. Benjamin Simonds, in Brig. Gen John Fellows Berkshire County brigade. 48 men were under his command according to Massachusetts Soldiers & Sailors. Amos and his men passed the winter in garrison for 97 days and service ended at the end of March 1777. While the records say that they marched at the beginning of January 1777 to Fort Ticonderoga to reinforce the Continental Army, and were there in February 1777, the pension records show a different itinerary:

Paul Baker – “That in the month of December 1776, and as this deponent believes on the first day of December he submits as a volunteer in a company commanded by Captain Amos Rathbone, lieutenant James Hubbard, Col. Simonds regiment, for the term of three months at the town of Pittsfield in the State of Massachusetts in which town this deponent then resided…That on the 18th day of the said month of December he marched with his company for New York. They marched as far as the town of West Stockbridge and, there, counter orders came to march to Albany, where they immediately marched and arrived there on the 22nd day of December…That they left Albany the day after Christmas, and marched to Fort Edward on the Hudson River and lay there two days; then marched to Fort Ann; and then to Ticonderoga on Lake Champlain… That the troops lay there and kept the fort until the 18th day of March 1777 when the company of Capt. Rathbone, and the other militia were all publicly discharged by the orders of the Colonel. They marched down on to the ice and were there discharged. “

Asa Graves – “That I was drafted from Richmond Massachusetts on the 20th December 1776 and joined the company under the command of Captain Amos Rathbun and the Regiment commanded by Colonel [ ] and marched to Albany State of New York thence we marched to Ticonderoga at the fort in the State of New York and remained at the fort until the 20th of March 1777. General Schuyler was there a part of [ ] the winter and has a verbal discharge the 20th of March after I has served these months.”

The Baker pension shows that Amos’ company was at Ticonderoga in time for what is known as the Christmas Riot, where soldiers from Pennsylvania raided the Massachusetts encampment “armed with guns, bayonets and swords, by force entered the tents and huts of officers and soldiers, dragging many out of doors naked and wounding them, robbing and plundering.” It was an oddly disturbing interstate rivalry and we can only imagine if Amos was amongst the ruckus – no one died. That episode aside, Ticonderoga was very busy over the winter of 1776, similar in scope to the winter of 1775, but far more pressing given the declaration of war, with repair and improvement to the fort and its facilities and defenses.

Alarms

On 11 May 1777, Amos was called out on alarm to march from Pittsfield to Kinderhook for a week. “And also in the Summer 1777. Turned out in an alarm under Capt. Amos Rathbun from the said Town of Richmond aforesaid to Columbia County State of New York six days. Disencamped at Kinderhook in the said County of Columbia.” (Eleazer Miller) Also, “in June of the same year about the middle I again volunteered under Capt. Amos Rathbone and joined the army at Fort Edward and marched from there to Fort George both places in the State of New York and there [ ] the return of the American army was at that time with the army one month and a half about the 10th of August in the same year.” (Jonathan Skeel)

Fort Ann 1777

The battle of Fort Anne was on July 8, 1777, on the heels of the battles of Ticonderoga and Hubbartown. Amos was called into service from July 8 to July 26 as a Captain of a company of militia under Maj. Caleb Hyde to reinforce the Northern Army. Amos’ company consisted of himself, 2 Lieutenants, 3 sergeants, 1 fifer, and 35 privates. The record of a private in his company states that they marched toward Fort Ann but were dismissed 97 miles from home. The pension application of Samuel Standish gives some interesting color on this time. Standish was from Stockbridge and had served at White Plains under Simonds and Rossiter. On July 8th, Standish was called out and served under Capt. Aaron Rowley, who was personally close to Amos and a Richmond neighbor. Standish was “on guard duty until July 17, when Indians attacked the picket post, firing upon the guard.” Standish was captured (though later escaped home the same year), and while in captivity saw Jane McCrae with another group of Indians when she was killed and scalped on July 27. Jane had been taken prisoner and, while on the Tory side, the story of her murder was told far and wide as propaganda throughout the colonies and served to rally the American cause.

Bennington

The muster rolls that cover the Battle of Bennington, which was technically in Walloomsac, New York, are located in 77 volumes in 81 boxes sitting the office of the Secretary of State in Boston. They have not been digitized. Thus, we have to rely on someone who went through these boxes, and produced the massive collection of volumes called “Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War – A Compilation from the Archives, Secretary of the Commonwealth, Boston, 1896” in which there are 22 soldiers listed as serving under Amos at the time of the battle. We can also rely on pension applications and some historical texts. The size of the Bennington battle, however, was far smaller than the collected troops at White Plains or Saratoga, as the battle materialized quickly. Regardless, through these sources, and other accounts of the battle, we can paint a picture of what Amos encountered – particularly having served under David Rossiter.

Arthur Latham Perry, a history professor at Williams College, actually went through the records in Boston. In his Berkshire Book, published in Pittsfield in 1892, before the publication of Massachusetts Soldiers, in a chapter entitled “Berkshire at Bennington” he writes, “I do know that nearly all the Berkshire men who were in the Battle of Bennington were mustered in that day, the 14th of August; so the pay-rolls at Boston bear the record to this day….I have recently searched the archives in the Secretary’s office for these rolls and have been reasonably successful, but I have not yet found them all…Capt. Nehemia Smedley – I hold in my hand the original pay-roll of 32 non-commissioned officers and privates who marched with him to Fort Edward, by order of Gen. Schuyler, and returned July 24, 1777, only 21 days before came the call to Bennington. This roll is sworn to by him before Isaac Stratton.”

These dates line up exactly with Amos’ service at both Fort Edward and Bennington, the record of which comes from Massachusetts Soldiers and not an image of the actual roll. Perry describes what he sees on a roll – “The heading of the South Williamstown roll is as follows: – “A pay-roll of Capt. Samuel Clark’s company, in Col. B. Simonds’ regiment of militia, County Berkshire, who were in the battle of Walloomsack, near Bennington, on 16th of August, who marched by order of Col. Simonds, including time to return home, after they were dismissed from guarding provisions to Pittsfield, being 20 miles from home, Aug. 14-21, 8 days.” Perry also has the rolls of Col. Brown and Col. Ashley, and notes that, from Richmond marched Capt. Aaron Rowley, with 26 men, and with them Lieut.-Col. David Rossieter of Col. Brown’s regiment.

As was common during the war, the composition of military units was constantly changing. In the Berkshire regiments, Amos was first a captain from Richmond in May 1776 in Col. Simonds 2nd Berkshire regiment. In December 1776, Amos was a captain again under in Col. Simonds. In the spring of 1777, he was again a captain in Simonds regiment when John Brown was made Colonel of the 3rd Berkshire regiment, David Rossiter was made Lieutenant Colonel and Caleb Hyde was made 1st Major.. In July of 1777, Amos is made a Captain in Maj. Caleb Hyde’s detachment, with his company consisting of 2 Lieutenants, 5 Sergeants, 3 Corporals, 1 Fife, and 35 Privates. A full-strength Company would have 96 men including 76 privates. Aaron Rowley was also a Captain in this regiment at this time. At the time of Bennington, Amos is called up under David Rossiter, as seen in Massachusetts Soldiers:

Captain, Liut. Col. David Roseter’s detachment of miltia; pay roll of a part of said Rathbun’s co. made up for service from Aug. 15 to Aug. 21, 1777, with Northern army

In Smith’s “History of Pittsfield” it is said that “Of the Berkshire militia districts, Col. Symonds..marched his full regiment. Col. Brown, the commander of the middle district, in which Pittsfield lay, was absent; and the detachment of his corps was led, and commanded with great spirit and military skill, by Liet.-Col. David Rossiter of Richmond.” Rossiter lived in Richmond, as did Amos, and Brown lived in nearby Pittsfield, which borders Richmond. The walk from Pittsfield to the battlefield in Walloomsac takes about 14 hours. Amos’s company would have marched north from Pittsfield to Williamstown and then to Pownal, from which they could have gone northeast through Bennington or northwest through Hoosick.

Of the men in Amos’ company that show up in Massachusetts Soldiers, there are many relationships to other rolls under Amos. The oldest is of Stephen Tambling, who was a drummer in White Plains, and remained so, but did not fight at Bennington as he and some others were separated off to guard the stores. Three Cogswell members were there – Israel, Nathan, and Rufus. Rufus served at Saratoga, and another brother, Samuel, served in the forts. Joseph Holley’s brother, Jonathan, served in the forts. Ebenezer Welch’s relations, Joseph and Walter, served at Saratoga. Jacob Bliss served in the forts and Saratoga. Benjamin Ingham’s relation, Joseph, served in the forts and at Saratoga. Other families served under Amos at the forts and Saratoga, but not at Bennington: Hill, Hatch, Patterson, Skeele, Tilden, Lusk, Griswold, and Dewey. While on the topic of family, it’s notable that Aaron Rowley, Jr. and John Rowley both served under Amos at Saratoga; their father, Aaron, was another Captain under Rossiter who also served at Bennington among other places. A pension record that places Amos there is that of Benjamin Waters (Warters), whose relations also served with Amos at the forts in July (Edward) and Saratoga in the fall.

Benjamin Waters (Warters) – Massachusetts Soldiers: “Private; pay roll of part of Capt. Amos Rathbun’s co., in Liet. Col. David Roseter’s detachment of militia, which marched to join Northern army; entered service Aug 15, 1777; discharged Aug. 21, 1777; service, 7 days. Roll sworn to in Berkshire Co.” His pension includes: “Olive Dewey…that she has resided there upwards of fifty years, that she has heard the foregoing declaration of Benjamin Waters and knows the contents thereof, that she has been acquainted with him upwards of fifty years that she first became acquainted with him during the revolutionary war and while he & this deponent both resided in Richmond in the state of Massachusetts that they lived near together & that she has lived within about two miles of him ever since he returned…that the said Benjamin was always called a man of truth & veracity…That she remembers that the said Benjamin together with the husband of this deponent were both in Bennington Battle under Gen. Stark… That she recollects that said Benjamin was drafted & went into Captain Rathbone’s company & was gone in the north in the service how long they were gone she cannont tell, she was well acquainted with Captain Rathbone.

The battle itself began on the 14th when Stark first met Baum’s troops. The 15th brought heavy rain all day, and the Berkshire militia arrived during the very early morning hours during the night of the 16th. They gathered on the East side of the Walloomsac River. In the morning, the Berkshire militia started out in the reserve, with Stark himself. Stark sent certain troops forward in an encircling action of the prominent “Hessian Hill” from two sides, which is now the site of the State Historic Site. Stark and the Massachusetts militia attacked the German Grenadier breastwork at the bottom of Hessian Hill near the bridge. This is shown as position “D” in both Liet. Desmaretz Durnford’s original battle map and also the 1780 engraving by Fadden based on the work of this British engineer. It sits between current Route 67 and the Walloomsac River in a wooded area that overlooks the bridge. Further understanding of the actual positions is aided immensely by the 1989 publication of bulletin 473 by the New York State Museum, “War Over Walloomscoick – Land Use and Settlement Patter on the Bennington Battlefield – 1777.” The Stark and Massachusetts route was along what is now Cottrell Road, across the Walloomsac River on the eastern of two bridges (where there is now only one – on Caretaker’s Road), and to the breastworks around 500 feet northeast of Route 67 by way of the river flats. Baum deployed a 3lb cannon towards the force.

It was a two-hour fight and, as Stark wrote, “was the hottest that he had ever seen: it was like one continued clap of thunder.” This, from a man who had been at Carillon under Abercrombie in 1758, served in Robert Rogers’ Rangers, and was also at Bunker Hill and Trenton. When victory was apparently at hand, a relief force sent by Burgoyne arrived under Col. Breyman from the West. “Col. Rossiter distinguished himself by coolness, zeal, and courage in his exertion to collect the men and restore order” and, at that critical moment, Col. Seth Warner arrived with his Vermont Green Mountain Boys from the East. Patriots that had been chasing fleeing Tories encountered Breymann coming Eastward up the road (Route 67). They were pushed back almost to the bridge, then rallied, with the battle resuming between the first engagement at the bridge and what is now the village of Wallomsac. Captured three pound cannons were brought into action against the Tories. Breymann retreated to the West. Over the course of the battle, the American losses were around 30 killed and 40 wounded, while the enemy had 692 captured and 308 killed or wounded.

A picture of the battle from the Massachusetts militia perspective comes from Rev. Thomas Allen, who graduated from Harvard at 19, studied under John Hooker, was the first congregational pastor in Pittsfield, and a cousin of Ethan Allen. On August 16th, the actual day of the battle, Allen wrote in his diary and then sent a letter to the Connecticut Courant, which published it on August 25, 1777. In it, he describes the entire scope of the battle, often in colorful language that one would expect of a preacher, and certainly insightful to a modern reader who hasn’t been in a black powder & edged weapon encounter of that sort. Relative to what the Berkshire militia, and Amos, were doing in the battle, Allen writes:

“Gen. Stark, who was at that time providentially at Bennington, with his brigade of militia from New Hampshire State, determined to give him [Gov. Skeene] battle. Col. Simonds’s regiment of militia in Berkshire County was invited to his assistance; and a part of Col. Brown’s arrived seasonably to attend on the action; and some volunteers from different towns; and Col. Warner, with a part of his own regiment, joined him on the same day. The general, it seems, wisely laid his plan of operation; and, Divine Providence blessing us with good weather, between three and four o’clock P.M. he attacked them in front and flank, in three or four different places at the same instant, with irresistible impetuosity. The action was extremely hot for between one and two hours. The flanking divisions had carried their points with great success, when the front pressed on to their breastworks with an ardor and patience beyond expectation. The blaze of the guns of the contending parties reached each other. The fire was so extremely hot, – and our men easily surmounting their breastworks, amid peals of thunder and flashes of lightning from their guns, without regarding the roar of their field-pieces, that the enemy at once deserted their cover, and ran; and in about five minutes their whole camp was in the utmost confusion and disorder. All their battalions were broken in pieces, and fled most precipitately; at which instant our whole army pressed after with redoubled ardor, pursued them for a mile, made considerable slaughter among them, and made many prisoners. One field-piece had already fallen into our hands. At this point, our men stopped the pursuit to gain breath, when the enemy, being re-enforced, our front fell back a few rods for convenience of ground, and being directed and collected by Col. Rossiter, and re-enforced by Major Stratton, renewed the fight with re-doubled ardor, and fell in upon them with great impetuosity, put them to confusion and flight, and pursued them about a mile, making many prisoners. Two or three more brass field-pieces fell into our hands, and are supposed to be the whole of what they brought with them. At this time, darkness came upon us, and prevented our swallowing up the whole of this body. The enemy fled precipitately the succeeding night toward the North [Hudson] River….This victory is thought by some to equal any that has happened during the present controversy….It is the opinion of some, that, if a large body of militia was now called to act in conjunction with our northern army, the enemy might be entirely overthrown.” (History of Pittsfield, Smith)

Saratoga

Allen’s thoughts came to be. Within a month of coming home after Bennington, Amos was once again in service at Saratoga. The two conflicts were inherently related and, undoubtedly, the success at Bennington influenced the ultimate outcome at Saratoga. The overall battle consisted of three major engagements: Stillwater on September 17, Freeman’s Farm on September 19, and Bemis Heights October 7. These were followed by Burgoyne’s surrender on October 14. Amos’s 47-man company was organized around September 20 and put into service the next day, according to the Massachusetts Soldiers records: Captain, Col. John Brown’s detachment of militia; pay roll of said Rathbun’s co. made up for service from Sept. 21, 1777 to Oct. 14, 1777, having marched at request of General Gates. Pension records support this: “As a private upon a pay roll of Amos Rathbun Col. Brown from Sept 20 1777, 11 days.” (Tarbill)

Although Amos was in John Brown’s militia, it does not seem that Amos accompanied Brown on his Ticonderoga raid from September 12 through the 27th. Both men were very familiar Ticonderoga – Amos having wintered there twice and Brown having been part of the party with Ethan Allen that captured it in May 1775. Amos’s company is formed for service from September 21 at the request of General Gates and, at that point, Brown was in the middle of the Ticonderoga action. It seems unusual, but not impossible, that a company is put into service without its Captain present. Also, the pensions of the men in Amos’s company describe joining him on the East side of the Hudson. Until Gates returned, Amos and his men made their way from the Berkshires to the East side of the Hudson where Brig. Gen. John Fellows was amassing troops at the request of Gen. Gates. Eleazor Miller‘s pension stated that he “marched from Richmond aforesaid in same year of 1777 up to Gates Army in Saratoga State of New York and there joined Liet. Rieves. Stayed there five or six days from thence was ordered to a place called Tulls Mills on the East side of the North River and there put into Capt. Rathbone company under General Fellows.“

Brown returned from the Ticonderoga raid and joined his troops before the October 7 battle, where he was on the right wing under Major General Benjamin Lincoln in Brig. Gen. Jonathan Warner’s Brigade of 1,768 militia. Also serving under Lincoln was Col. Daniel Morgan’s Corp of Rifleman and the brigades of Brig. Generals John Glover, John Nixon, and John Paterson.

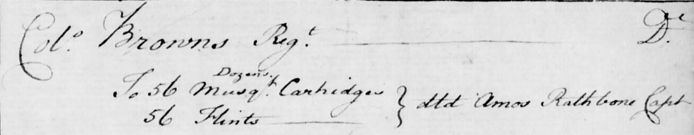

We know Amos is in Bemis Heights on September 28 because there’s a record of him drawing of 56 dozen musket cartridges and 56 flints, giving him a supply of 672 cartridges in anticipation of a potential attack on Gates’ headquarters at Bemis Heights.

This is in addition to other supplies distributed two days earlier:

Brown’s militia is notably under Brig. Gen Warner, and not with Brig. Gen John Fellows, where much of the Berkshire militia served. Gates had Fellows stay south of Bemis Heights as an option to deploy against Burgoyne depending on the outcome of the upcoming engagement. Immediately after the October 7 battle, Gates ordered Fellows and approximately 1,300 other Berkshire militia to move north up the east side of the Hudson river to the mouth of the Battenkill river, which is just north of Schuylerville, and there cross the Hudson to the west side and dig in on the heights of Saratoga. Fellows’ militia crossed the Hudson at Stillwater at the mouth of the Hoosick River. On October 9, General Fellows followed orders to withdraw his militia back to the east side of the Hudson River and positioned them to guard the river crossing at Schuylerville at the Battenkill and to cover the British retreat with cannon fire.

Despite being well armed, we know from the history of the October 7 battle that Burgoyne’s army never made it to Gates’s position on Bemis Heights, where Warner’s division was at the northern point at Neilson’s Farm. We also know from a pension record (Thomas Kellogg) that Amos’ company was not in the action at Bemis Heights: “was within one mile of the Battle ground, at the time that Burgoyne was taken, Capt. Rathbun company not having called into the action, and of Burgoyne had surrendered he the said Thomas Kellogg returned with Capt. Rathbun to Pittsfield, and had served in this tour two months.” The fighting on October 7 was, indeed, one mile from the Bemis Heights camp. Kellogg’s recollection, however, glosses over the fact that Burgoyne went into retreat and did not surrender until October 14. Another pension (David Holly) fills in the void between the capture and Amos’s return home. “This deponent also saith that in the year 1777 being the year in which Burgoyne was taken he the deponent was at Stillwater in the State of New York in the service of the United States. That while there his brother Jonathan came there with Capt. Amos Rathbone. That this deponent went home [ ] before the capture of Burgoyne and left Jonathan Holly at Stillwater in service under the said Rathbone.” Stillwater is about six miles south of the Bemis Heights camp, on the West side of the Hudson River, while Schaghticoke, New York is a few miles to the East. This was a primary river crossing place, right where the Hoosick River meets the Hudson.

Thinking about the return of the company back to the Berkshires, it is interesting to trace the initial route from the Berkshires to Saratoga. This was a well-established path. Travel west than north up the Hudson, or north from Pittsfield to Williamstown, then west through North Hoosick (then called San Coick or St. Croix) and cross the Hudson to Stillwater, and then north through Saratoga to Fort Edward, Fort Anne, Fort George, and Ticonderoga. Amos had traveled these routes many times, from his service in the French & Indian War, to various points during the Revolution including alarms, winter at Ticonderoga, and the Battle of Bennington.

Tulls Mills does not show on any contemporary maps, although there are Tull families in the 1789 census around Greenwich, New York. Tulls Mills appears to have been positioned west of North Hoosick, then called San Coick, on the Hoosick River before it meets the Hudson at Stillwater. The diary of David How describes, having left Stillwater, crossing the Hudson, travelled along the Hoosick River to San Coick, around 20 miles, and that along this route at Tull’s Mills a man had been killed. In the diary of David How (pg 47, second journal), Oct 9 1777, “this morning we set out marchd through Willims Town & Pownal and stopt at East Who-suck. Oct 10 – This morning we set out marchd through old Who-Suck and Saint Cook and at Night we stopt at Cambridge. Oct 11 – This morning we march to Salletoga”. Howe’s return trip also places Tulls Mills to the west of Hoosick: “Oct 19 – This day we have ben fixing for a march and at noon we set out with the prisoners for to Guard them to Boston and at Night we all stopt and encamed Tulls Mills. Oct 20 – This day marchd 5 miles to Saint Cork whare we stopt and encamped waiting for the wagons & sick. Oct 24 – “this morning we set out marchd through Lainsborough, Staid at night at Pitsfield.” The journal of Samuel F. Merrick, a doctor from Wilbraham, Massachusetts also describes the troop movements on the East side of the Hudson as Burgoyne is retreating, and his movements closely match the descriptions in the pensions of Amos’ and Fellows’ movements. Merrick describes having left his horse in Williamstown on October 4, 1777, marched on foot for four miles on the road to Bennington, then turned to the left and went about six miles, then five more miles to “Tulls mills so called, lodged at one Tyashoke” on Oct 5th. On Oct 6th, from Tulls Mills, “found that our troops were all ordered up the River, ordered to encamp till further orders.” In the afternoon, “heard canon briskly towards head quarter.” On Oct 7th, “This day about four o’clock cannon play very briskly followed with small arms & continued till dark, went upon guard this night.” On Oct 8, “this morning an express arrive from head quarters informing that Gen. Gates had carried sundry Redoubts & all the Enemys outlines and twas expected by the motions that they would retreat soon, likewise with orders for us to Press forward with all dispatch, accordingly half after twelve we marcht and travilled till sunset about twelve miles.” Oct: 9: “two expresses arrived informing that the enemy were actually on the retreat, orders for us to make no delay in order to harass them upon their retreat. Set out very early and arrived at Batten Kill before noon about three miles from Saratoga, a very rainy afternoon.” Oct 14: “Ordered that there be a cessation of arms till sun set.”

Fishkill & Mohawk Alarm

On March 30, 1778, Amos is on a muster roll dated Richmond and on April 20, 1778, “Capt. Rathburn appears as shown below on a List of the Men Raised in the County of Berkshire in the State of Massachusetts Bay for the Purpose of filling up and Completing the Fifteen Battalions of Continental Troops Directed to be raised for the Term of Nine Months from the Time of their Arrival at Fish Kill”. Service thus ended December 1778. George Washington’s headquarters were at Fishkill in September and October of 1778, which means Amos must have seen him regularly. Fishkill was a significant military distribution hub on East side of the Hudson River. At this time during the war, the British under Butler and Indians under Brant raided and burned the Mohawk and Schoharie river valleys. It remains unknown what actions resulted from these orders for Amos, but he was not at the notable battle of Stone Arabia in October 1778 under John Brown with 300 militia, when Brown was killed and 45 were killed or scalped.

From here, nothing else has been found yet in the records. The war is still going on, particularly to the West in the Mohawk valley, and we see men formerly associated with Amos serving at Stillwater in October 1780 and again at Saratoga in October 1781. At this time, Amos is 40 years old. Presumably, he returns to the Berkshires and his farm – and the war may have changed him, as his next personal decisions demonstrate.

The Shakers

Amos was a member of the Richmond Congregational Church. Just to the north, the Congregational Church in Pittsfield was served by Thomas Allen as its minister, with whom Amos and his brother Valentine worked closely with during the Revolution, and with whom Amos served in White Plains and Bennington. In 1772, Valentine had formed the Pittsfield Baptist Church. At nearly the same time, in 1775, the founder of the Shakers, Ann Lee, and her followers moved from New York City to a tract of land northwest of Albany in Nisquenia (now Watervliet), around 30 miles from Pittsfield. In May of 1780, Valentine went “to see a new and strange people living there…and on the 26th of May we arrived at Nisquenia.” In a “tumult of thought” he joined the Shakers along with some children and brothers Daniel and Amos. This was in 1780, when Amos was aged 42. Perhaps a lifetime of war from the age of 19 had driven him toward more spiritual matters. Yet the Shakers were an unusual choice, with their basic tenants of celibacy, communal life, separation from the world, and pacifism – and the veneration of Ann Lee as the second coming. Although a religious life is obviously possible without the extremity of Shaker views, Amos came from a particularly religious family not unknown to strong views. As mentioned, his father helped found the Baptist church in Stonington. His maternal grandfather was Valentine Wightman, founder of the first Baptist church in Connecticut; Valentine’s great grandfather, Edward Wightman was, in 1612, the last man burned at the stake in England for his religious views.

The Shakers anti-war and anti-government stance was clearly contrary to Amos’ prior life. Beyond the political and sexual stance (separation and no procreation), Amos’ brother, Valentine, saw “inconsistencies and falsehoods.” By December 1780, he had not only left the Shakers, but published a 24-page pamphlet attacking them: “Some Brief Hints of a Religious Scheme, Taught and propagated by a Number of Europeans, living in a Place called Nisquennia, in the State of New York.” Daniel left in 1785, and also published a rebuking pamphlet, as did Valentine’s son, Reuben, in 1799. Amos, however, was not swayed and remained a Shaker. His wife, Martha, refused to join, and his children moved westward toward the Finger Lake region of New York, ultimately settling in Yates County. Despite the stance of his wife and brothers, Amos was an active part of the Hancock Shaker community, and became a teaching elder. Upon hearing him recite, “Mother Ann” Lee once said, “Amos, thou shalt sing bass in heaven.” (Rufus Bishop, compiler, A Collection of the Writings of Father Joseph Meacham Respecting Church Order and Government, New Lebanon, NY 1850). The following are mentions of Amos from Mother Ann Lee’s 1816 “Testimonies”:

Testimonies

Amos Rathbun asserts, that he felt such an extraordinary out-pouring of the power of God, that it filled him full from heat to foot; insomuch that it seemed as though he should burst if he did not speak. He saw with great clearness, the great loss and awful state of fallen man, and the great salvation and glory now offered, and to be attained by the gospel. As soon as Father William had done signing, Amos was constrained to cry out, and warn the world of their state – of the great salvation offered by the gospel, and of the awful consequences of losing the day of their visitation. (6, page 173)

At Watervliet, in the former part of the year 1781, Elder James took Amos Rathbun by the hand, and prophesied, saying, “In eleven years the Church will be established in her order.” This prophecy has been exactly fulfilled., for in the year 1792, the Church was established in the present order and spirit of government. [A.R.] (17, page 218)

Mother then spoke to Father William, saying, “Brother William, take this man into another room, and labor with him, and take Amos with you.” They accordingly went, and Father William labored with the man, and put the things that Mother had told him of, so close to his conscience, that, after considerable labor, in which the man seemed almost speechless, he at length, confessed, that Mother had told him the truth. [A.R.] (30, page 252)

At Harvard, in the autumn of 1781, there came a man who professed faith, and opened his mind to one of the Elders; but Mother, not feeling satisfied with him, called Amos Rathbun, and told him to go and labor with the man; “for (said she) he has pretended to open his mind; bet he has not done it honesty; he has defiled himself; do you go, Amos, and make him confess it.” (31, page 252)

Accordingly, Amos went and labored with the man, who pretended to make cull confession of the matter; but he did not tell it, truly and honestly, as it was. Mother still feeling and knowing the man’s hypocrisy to Amos also, went into the room herself, and spoke to the man, with great sharpness and severity, saying “You cover your sin, and do not confess it honestly – You have defiled yourself. (32, page 253)

These words were spoken with such power of God, that the man was struck down, and fell, with his whole length upon the floor, groaned out and said, “It is true;” and appeared to be in a desperate agony, and, for some time, was unable to rise up. While he lay in that situation, Mother sharply reproved him, for such filthy and abominable conduct, and for not confessing it to Amos, when he was called upon; and declared to him the impossibility of ever keeping the way of God with sin covered.” (33, page 253)

Again, at Harvard, Mother called upon Amos Rathbun, one evening, and informed him that a certain man, in the neighborhood, had been there to open his mins; “but (said she) he has not been honest; he has kept his doleful sins covered.” It being then late in the evening, Mother bid Amos go to the man’s house, and if he was in bed, to make him get up and confes his sins. (34, page 253)

In obedience to Mother, Amos went, feeling at the same time a great weight of tribulation, and praying, all the way, that he might answer the mind and will of God, and see Mother’s face in peace, at his return. He found the man in bed, and desired him to get up; for he wanted to talk with him, and he could not answer his mind by talking with him in bed (35, page 254)

The man arose from his bed, and according to Mother’s directions, Amos told him of those sins which he had kept covered, and had not honestly brought to the light, as he outght to have done. The man was greatly struck, acknowledge the truth of Amos’s words, and appeared to be much broken down. The next day he came to the Square-house, and said, “There was a man came to my house last night, and told me the very truth.” (36, page 254)

On the other hand; the torments and misery of those who will be finally lost, though they may be under never so much; yet, what they feel, in the present tense, will not be their greatest torment; but that which will constitute their greatest misery, will be, looking forward, with awful forebodings, to another opening of the judgements and wrath of God. This will continue, forever and ever, with those who will be finally lost.” [Amos Rathbun] (9, page 305)

At another time, speaking to Amos Rathbun of his own experience, after he embraced the gospel, he said, “Mother’s testimony was so awakening to my soul, that when I was at work over my anvil, I sometimes felt so weary, that I would have given anything if I could have sat down upon my anvil one minute; but I durst not; for I felt my soul in continual labor to God. And often times when I went to my meals, I felt so unworthy to put any of the creation of God into my mouth, that I could not eat; but wept, and went back to my work again.” (11, page 336)

Again, he said to Amos Rathbun, “The same sword that persecutes the people of God, will be turned into the world among themselves and never will be sheathed until it has done the work.” (29, page 341)

Again he said, “The judgements of God will as certainly follow the preachings of this gospel, as the flood followed the preaching of Noah; and the same sins that brought the judgments of God upon Sodom and Gomorrah, will bring the same judgments upon the inhabitants of the earth; for the sins of Sodom are already in the earth. [Amos Rathbun]” (45, page 365)

Death

Amos’ death in July 1817 is recorded in the Shaker records and he is buried in the community cemetery on what is now Leabanon Mountain Road (Route 20) in Hancock, Massachusetts. As was the practice, there are no headstones for the individual graves, but a common marker still stands. His wife, Martha, died shortly after the Revolution in 1788, just eight years after Amos joined the Shakers, and when her daughter, Anna, was just 13. Fortunately, Martha had the comfort of children and, hopefully, some fond pre-Shaker memories of her husband, who certainly led an extraordinary life.