Rhode Island

1638...

My father, four grandparents, and two dogs are buried on Aquidneck Island but below, in chronological order, are some much earlier ancestors that joined in the lively experiment of the Colony Rhode Island and Providence Plantations at the very beginning. I have also included some original documents capturing early life on Aquidneck Island, and a chronology of Newport in which the historical record presents a different picture than the common narrative.

Richard Smith 1589-1666

Richard Smith appears as one of the first inhabitants of Newport on May 20, 1638, just two months after the signing of the Aquidneck compact and a year before the formal formation of the town. Around 1638, and certainly with the help of his friend, Roger Williams, Richard purchased a substantial 30,000 acre tract of land in Narragansett territory called Cocumcussoc, where he set up a trading post on the Pequot path. Richard kept his Aquidneck lands but moved with his family and a group of people to New Amsterdam in 1642 for religious and personal reasons. They settled on Long Island at Maspeth in present-day Queens. Indian hostilities forced them to Manhattan, which then had a population of around 300. Richard was on Dutch West India Company Director-General Willem Kieft’s council of Eight Men, and had a waterfront lot on what is now Stone and Pearl streets on the East River. He traded extensively on his bark, the WELCOME, between Manhattan and Cocumcussoc, and was also involved in trade to the Caribbean, and Barbados in particular. He owned land on both Jamestown and, immediately to its west, Dutch Island, in Narragansett Bay. He moved back to Rhode Island after 1648 and purchased Roger Williams’ trading post, near his own, in 1651. He resumed an active life on Aquidneck and was serving on the Grand Jury by 1649, but he was also sailing back to Manhattan at least through 1659. He sold all his New Amsterdam properties by 1662, just two years before the death of his wife, Joan Barton, and four years before his own death at Cocumcussoc.

Philip Shearman 1611-1687

Philip Shearman 1611-1687

Philip arrived in New England 1623, originally settling in Massachusetts, where he married Sarah Odding. They were associates of Anne Hutchinson, with whom they left Massachusetts Bay for Aquidneck Island. Philip was a signer of the Aquidneck Compact on March 7, 1638, and a grantee in the 1638 deed for the island. Philip held several offices in the colony, including that of the first Secretary, and appears frequently in the records sitting with Roger Williams. He also served in many roles for the town of Portsmouth, including town council and town clerk. During King Philip’s War, the Rhode Island General Assembly on April 4, 1676 “Voted that in these troublesome times and straites in this Collony, this Assembly desireinge to have the advice and concurrance of the most juditious inhabitants, if it may be had for the good of the whole, doe desire at their next sittinge the Company and Council of…Mr. Philip Shearman.” In his will, he left his flock of sheep to his wife and, to his children, gave Portsmouth farmlands and houses, Narragansett horses, Dartmouth (Massachusetts) lands, cattle, more horses, swine, oxen, goods and “New England silver money.”

Adam Mott 1596-1661

Adam, from Cambridge, arrived with his second wife, Sara Lott, and family in Boston on October 8, 1635 on the DEFENCE, from London. They settled first in Hingham. He was a tailor. They were in Portsmouth by 1638 and Adam shows up prolifically in the town records. He received 145 acres in Portsmouth on the western Narragansett side of the island, where his son, Jacob, built a stone-ender house that stood until 1973, amongst the oldest houses in the state. After Portsmouth and Newport joined, Adam appears at the General Court in March 1642 where, in consideration of the formation of militia for Aquidneck, he is elected as the clerk of the Portsmouth militia, responsible among other things for the the “Traine Bands” to be exercised monthly. Adam’s father, John, also came to Portsmouth and he was supported by the town. On June 9, 1652, the town “agreed that there shall be a stone house built for the more comfortable being of old John Mott in the winter” and on January 23, 1655 it was agreed that “the town will be at the charge to pay old man John Mott’s passage to Barbades Island and back again if he cannot be received there, if he lives to it, if the ship owners will carry him.” John survived, for he shows up on Aquidneck subsequently in 1655-1656. Adam was likely a follower of Anne Hutchinson as a Massachusetts constable’s detachment went to seize him on September 6, 1638, but he had already fled the colony. Adam’s 1661 will named “my faithfull friends Edward Thurston and Richard Tew both of Newport on Rhoad Iland” as executors. His estate was left to his wife, and included his “house and land, four oxen, five cows, a bull, a horse, one mare, a colt, two calves, thirty ewe sheep, two rams, six swine, 3 pounds in wampum peage, clothes, books, two feather beds, two flock beds, six pewter platters, a wine pot, warming pan, seven pair of sheets, six napkins, two tables, a joint stool, and one and one-half acres of wheat, two acres of oats, two acres of peas, and three acres of Indian corn.” His son, Adam (1623-1712), from his widow Elizabeth, married his stepsister, Mary Lott, Sarah’s daughter, who also sailed on the DEFENCE.

stood until 1973, amongst the oldest houses in the state. After Portsmouth and Newport joined, Adam appears at the General Court in March 1642 where, in consideration of the formation of militia for Aquidneck, he is elected as the clerk of the Portsmouth militia, responsible among other things for the the “Traine Bands” to be exercised monthly. Adam’s father, John, also came to Portsmouth and he was supported by the town. On June 9, 1652, the town “agreed that there shall be a stone house built for the more comfortable being of old John Mott in the winter” and on January 23, 1655 it was agreed that “the town will be at the charge to pay old man John Mott’s passage to Barbades Island and back again if he cannot be received there, if he lives to it, if the ship owners will carry him.” John survived, for he shows up on Aquidneck subsequently in 1655-1656. Adam was likely a follower of Anne Hutchinson as a Massachusetts constable’s detachment went to seize him on September 6, 1638, but he had already fled the colony. Adam’s 1661 will named “my faithfull friends Edward Thurston and Richard Tew both of Newport on Rhoad Iland” as executors. His estate was left to his wife, and included his “house and land, four oxen, five cows, a bull, a horse, one mare, a colt, two calves, thirty ewe sheep, two rams, six swine, 3 pounds in wampum peage, clothes, books, two feather beds, two flock beds, six pewter platters, a wine pot, warming pan, seven pair of sheets, six napkins, two tables, a joint stool, and one and one-half acres of wheat, two acres of oats, two acres of peas, and three acres of Indian corn.” His son, Adam (1623-1712), from his widow Elizabeth, married his stepsister, Mary Lott, Sarah’s daughter, who also sailed on the DEFENCE.

Edward Robinson 1615-1690

First appearing in colonial records in 1634 at the age of 18 on a ship from London bound for Barbados, and first appearing in Rhode Island records in 1643 in Newport for trespassing, Edward Robinson lived a complicated, but not then uncommon, dual-existence sailing between Barbados and Newport. In Newport, he served on grand juries in the presence of Governor Benedict Arnold, John Clarke, John Cranston, John Coggeshall, and Roger Williams. Barbados was only settled in 1627, with Edward arriving shortly thereafter in 1634, nearly six years before sugarcane was introduced to the island. He died in Barbados in 1690, having witnessed and participated in the exponential changes on the island, and ultimately owning significant plantations. He led a very busy life that ultimately became more complicated than he likely expected: a wife and children in Barbados, and an unexpected mistress and children in Newport.

George Wightman 1632-1722

George’s older brother, Valentine (1627-1700), moved from England to Rhode Island and appears in the early Providence records. Valentine was fluent in Algonquin and was well known to Roger Williams, Richard Smith, and John Winthrop. Undoubtedly, Valentine is the reason George came to Rhode Island. They were both devout Baptists. Both knew that their father, John, had witnessed their grandfather, Edward, burned at the stake as a heretic on Friday, March 20, 1612 in Burton-upon-Trent, Staffordshire, England. He was the last person in England to die that way. While there is not a detailed record of George’s immigration or activities once inside the colonies, it’s fair to assume that he headed to Rhode Island and Valentine’s influence. By 1663, George married Elisabeth Updyke, granddaughter of Richard Smith. George begins showing up in land and political records after this date, such as grand jury duty on September 14, 1687. He is one of the signed Narragansett petitioners to the King on July 29, 1679. In 1682, Valentine sold George his primary holding acquired in 1660, which Valentine called “Aquidnesset” in his will, but is more commonly called Quidnessett, a 100 acre plot north or Cocumcussoc that had Narragansett Bay frontage. Richard Smith (junior) and Lodowick Updyke were witnesses. George appears in numerous land transactions and, over time, his landholdings were near 2,000 acres. George & Elisabeth named one of their sons, Valentine, who married Susannah Holmes. George died just before his 90th birthday in 1722, predeceased by Elisabeth (born in 1644), who died in April 1716.

John Rathbun 1630-1702

With his name on the rock at the tip of Block Island as one of the original purchasers and settlers, with over 530 acres, John Rathbun and his wife Margaret carved out a life of farming, animal husbandry, trading, and rum distillation with properties on Block and in Newport. He was a representative in the Rhode Island General Assembly, a grand juryman, worked with William Brenton (who named John in his will), and was a proprietor of the town wharf. The Rathbun house in Newport, at what is now 8 Washington Square, was where, in 1763, the plans for Brown University were made. John, and his son, also had encounters with pirates on Block Island.

Zoeth Howland c1631-1676

While not a resident of Rhode Island, Zoeth and his family ran the ferry between Portsmouth and Tiverton, then part of Massachusetts. He was the son of Henry Howland, brother to John Howland of the MAYFLOWER. For his religious beliefs, Zoeth spent time in the stocks in 1658 and was fined, with his wife Abigail, for not attending services. Zoeth moved to Dartmouth, Massachusetts and became a Quaker and is in the Quaker records in Newport. On one of his trips to Newport, in the midst of King Philip’s War, he was killed by six Indians in March 1676 as he approached the ferry on the eastern shore, in what is now Fort Barton Woods in Tiverton. Zoeth’s attackers mutilated his body and dumped it in a stream which was thereafter named Sinning Flesh Brook, but is today called Sin and Flesh Brook. His son Daniel kept the ferry after Zoeth’s death and, even as late as the 1777 Blaskowitz map, adjacent, it is still called “Howland’s Ferry.”

Newport’s Creation Myth

Countless Rhode Island historical writings, from ancient publications to modern work, present the founding of Newport as an almost mystical event. As the common narrative goes, nine wealthy families who are wholly disgruntled with the way things are going on the Northern end of Aquidneck Island, pack their bags and travel South through virgin forest and arrive miraculously at Newport harbor in the Spring of 1639, where they set themselves up, declare that the “plantation be called Newport,” and launch a thriving society and government that subsequently influences the commercial and ideological course of America. Even today’s official seal of the City of Newport and numerous signs on the island inaccurately proclaim, “SETTLED 1639.” While Newport was founded in 1639, as a settled physical place, named town, and social and commercial ideal, Newport existed well before this as seen in period cartography, Dutch manuscripts, the writings of Roger Williams and John Winthrop, and original Aquidneck records.

Early Cartography

It was no secret that an excellent harbor existed at the Southern end of Aquidneck. Adriaen Block, after determining that Manhattan was, in fact, an island, proceeded East and contributed to a map in 1614 of Long Island Sound and Narragansett Bay. As Block’s map was based, in part, on the work of prior cartographers, combined with his new first-hand knowledge – which is shaded in green – some things are presented more accurately than others. Block clearly shows what is now Point Judith and Narragansett Bay, in which the first large island on the Western side is Jamestown, shown without Dutch island. The next is Aquidneck, with the unmistakable shape of Newport harbor on its Southwestern shore. It is to the East of Aquidneck that things get somewhat skewed in Block’s presentation. The Sakonnet River clearly extends up and connects with upper Narragansett Bay, but the Elizabeth Islands are drawn as a cluster that project out of Narragansett Bay rather than Buzzard’s Bay. Notable is Block’s notation of “sloupbay” which is now called the West Passage of Narragansett Bay (link). At the time, there was already a functioning trading post there called Quotenis (“Quetenesse”), which is now called Dutch Island, and trading also likely occurred along the Pequot path near Wickford where Richard Smith established his trading post at Comcumcussoc. Willem Blaeu’s 1635 map of the region draws heavily on Block, he also notes “Chaloop Bay,” puts Dutch Island in its proper place, gives Newport the name “Anckerbay” and names “Bay van Nassouwe” at the head of an apparently combined Narragansett and Buzzards bays. The “Nassau” on the older Dutch charts is applied broadly to Narragansett Bay and Buzzard’s Bay and their various rivers. The name was chosen because, at the time of Block’s map, Maurice of Orange-Nassau led the Dutch republic. Writing in 1625-1630, cartographer Johan de Laet describes sailing from Martha’s Vineyard (“Texel”) to Block Island where, at mid-journey, to the North is “situated first the river or bay of Nassau which extends from the above named Block’s Island northeast by east and southwest by west. This bay or river of Nassau is very large and wide, and according to the description of Captain Block is full two leagues in width….From the westerly passage into this bay of Nassau to the most southeastern entrance of Anchor Bay…our countrymen have given to names to this bay, as it has an island in the center and discharges into the sea by two mouths, the most easterly of which they call Anchor Bay and the most westerly Sloop Bay.” In this context, “Nassau” is Buzzard’s Bay, but others appear to ascribe the Sakonnet River to Nassau as well. That leaves de Laet’s description of Anchor Bay as the East Passage with Newport harbor and Sloop’s Bay as the West Passage with Dutch Island. This concept is reinforced by a letter from Isaack de Rasieres to Samuel Blommaert written around 1628 describing his arrival in New Netherland in July 1626 and a visit to Plymouth in October 1627. De Rasieres says that “coming out of the river Nassau, you sail east-and-by-north about fourteen leagues along the coast, a half mile from the shoure, and you then compe to ‘Frenchman’s Point’ at a small river where those of the Patucxet have a house made of hewn oak planks, called Aptucxet….here also they have built a shallop in order to go and look after the trade in sewan, in Sloup’s Bay and thereabouts, because they are aafraid to pass Cape Mallabaer…” (source) De Rasieres is describing the correct distance in nautical miles of a trip out of the Sakonnet River, then left and up to the head of Buzzard’s Bay to Bourne on the Manamet River, where a trading post existed (and exists today as the Aptucxet trading post museum) to avoid a journey outside Cape Cod (“Mallabaer”). That Sloup’s Bay is mentioned distinctly implies that the trading would therefore go from Aptucxet past the Sakonnet towards Newport and Dutch Island.

Early Trading

By 1637, the same year that the Aquidneck deed was written, the Dutch had already been actively trading in Narragansett Bay for years, even before the settlement of Manhattan. Dutch Island was (and is) and excellent harbor and its advantage over Newport was its closer proximity to the mainland’s Narragansett fur trade. Aquidneck’s mainland access was on the Sakonnet side, but the Sakonnet offered no ideal harbor, so Newport harbor was the likely nexus of Aquidneck trading – which was less robust than the mainland’s fur supply. The Dutch were so focused on this Narragansett trade that, in February 1651, Petrus Stuyvesant argued the New Netherland boundary claims included “therein Long Island, situate right in front of New Netherland, whence it is separated by an arm of the sea, called the East river, which begins at Coney Island, in the North bay of the North river, and runs again into the sea at the eastward, near Fisher’s Island, opposite the Pequatoos river, together with all other bays, rivers and islands situate westward of Cape Cod, and especially the island named Quetenis, lying in Sloop bay, which was purchased, paid for and taken possession of in the year 1637, on the Company’s account.” (link) Notable is Stuyvesant’s choice of the word “especially.” Coastal traders between Plymouth and New Netherland were certainly aware of, and likely used, Newport harbor, as did local trade occurring between these two commercial centers. As an example, in 1649, Roger Williams wrote from his Narragansett post to John Winthrop in Boston: “For preface, this Mr. Smith’s pinnace (that rode here at your being with us) went forth the same morning to Newport, bound for Block Island, and Long Island, and Nayantick for corn; with them went a Narragansett man, Cuttaquene, a usual travel for Mr. Smith: the wind being (after three or four days stay at Newport) northeast and strong, they put into your river and so to Mohegan.” Richard Smith’s neighbor on “Sloop’s Bay” was Roger Williams, and his neighbor on Manhattan was Isaac Allerton, who was in New Amsterdam by 1636 and likely stopped in Newport on his voyages. Allerton traded as far as the Caribbean and knew the importance of Narragansett Bay because, with William Bradford, they worded the patent of 1629/30 to state that the boundary of Plymouth encompassed all of Narragansett Bay. Isaack de Raisiers’ introduces William Bradford to sewan/wampum in trade when he writes that “the seeking after sewan by them is prejudicial to us, inasmuch as they would, by so doing, discover the trade in furs; which if they were to find out, it would be a great trouble for us to maintain.” (source) The source of sewan, from quahog shells, were the Narragansetts and Pequots in Narragansett Bay and Eastern Long Island Sound, respectively.

Early Naming Conventions

Howard Chapin, in his “Documentary History of Rhode Island” (V1, pg 40) mistakenly writes that “As early as the year 1636 the name Rhode Island was applied to Aquidneck, as is shown by the letter of Roger Williams to Deputy Governor John Winthrop, which from its context was evidently written in the late summer or early autumn of 1636, and dated at New Providence. It reads: They also conceive it easy for the English, that the provisions and munition first arrive at Aquednetick, called by us Rode-Island, at the Nanhiggontick’s mouth.” The letter in question was actually written in May 1637 and this use of “Rhode Island” predates the formal Aquidneck record of March 13, 1644. Similarly, Newport was a distinctly named place well before the formal naming and founding of the town on June 16, 1639 when it was determined that the new “plantation be called Newport.” A full year earlier, on the May 1638 list of Aquidneck inhabitants, there were 42 under the heading “Inhabitants admitted at the Town of Nieu-Port.” Notably, the document says “the Town of Nieu-Port” not simply a simple descriptive as “the new port.” A town is a distinct collection of people that reside together. In August 1638, Roger Williams, writing to John Winthrop, referred to the inhabitants of Aquidneck as “the islanders” and not something more specific such as “the people of Pocasset” and this broader term would appear to encompass both Pocasset and Newport. Later, in a letter from Roger Williams to John Winthrop on December 30, 1638, Roger says “I hear of a pinnace to put into Newport, bound for Virginia…” This is the first use of “Newport” in Roger’s writings. A boat that stops in Newport before sailing south is likely provisioning, which requires the support of people ashore to provide the requisite goods and services, particularly before the presence of docks and wharfs. Clearly, Newport was a named place inhabited by many people before Coddington’s company arrived and formalized the name and government in 1639.

Aquidneck Population Movement

Perhaps the most important, yet overlooked, document regarding the history of Aquidneck Island is the May 20, 1638 list of Aquidneck male inhabitants. I have not seen this analyzed in any historical writing on Rhode Island, yet it is instrumental in understanding Newport’s history.

The heading at the top of the manuscript says “A catalogue of such who, by the Generall consent of the Company were admitted to be Inhabytants of the Island now called Aqueedneck, having submitted themselves to the Government that is or shall be established according to the word of God therein.” This is followed by a subheading, “Inhabitants admitted at the Town of Nieu-Port.” Therefore, it can be presumed that the first list refers to residents of Pocasset. The Pocasset list contains 58 names, and the Newport list contains 42 names. This is only two months after the signing of the compact. Clearly, people didn’t linger around the cove and town pond at the Northern end of the island. Pocaasset had an enormous amount of religious and social drama. People immediately moved south and, however crudely, built lodgings in Newport. They were “inhabitants” which means they truly lived there, as settlers. This is a nearly a year before the separation from the Pocasset plantation on April 28, 1639 to “propagate a new plantation in the midst of the island“ by William Coddington, Nicholas Easton, John Coggeshall, William Brenton, John Clarke, Jeremy Clark, Thomas Hazard, Henry Bull, and William Dyre. These 42 residents were also living in the named town of “Newport” exactly a year before Coddington and company decided on June 16, 1639, that their new “Plantation be called Newport.” Shortly thereafter, Portsmouth was made the official name of the Northern settlement on July 1, 1639.

The Newport founding mythology was supported by Peter Easton’s writing, in 1669, about his experience in 1639: “In the beginning of May this year the Easton’s came to Newport in Road Island and builded there the first English building and they planted this year and coming by boat they lodged at the island called coasters harbor the last of Aprill 1639 and the first of May in the morning gave that island the name of coasters harbor and from thence came to Newport the same Day.” From an architectural perspective, this may have been the first “English” style building, but it was certainly not the first building or dwelling. That 42% – nearly half – of the island population was already living in Newport within two months of the foundational signing of the Aquidneck compact is significant. Not one of the future Newport “founders” are on the 1638 Newport list, while the Pocasset list includes Nicholas Easton, Jeremy Clark and Thomas Hazard. Missing from both lists are Coddington, Brenton, Bull and Dyre. Also missing are some of the Aquidneck compact signers. Perhaps the preamble to the list – “having submitted themselves to the Government that is or shall be established” by default includes those already named to the government which, at the Pocasset General Meeting on May 20, 1638, included: Coddington, Hutchison, Coggeshall, Baulston, Sanford, Wilbore, Porter, Freeborne, Walker, Shearman, and Dyre. Nevertheless, the “founders” are not on the Newport side of the ledger and, astoundingly, there are only seven people on the May 1638 Newport list that also show up in the 1655 list of Newport freemen. And one of them, William Baker, moved back to Portsmouth – as did William Brenton and Thomas Hazard. A further five from the 1638 Pocasset list were on the 1655 Newport list: Jeffery Champlin, Joseph Clarke, Robert Carr, Robert Stanton, and Nicholas Easton. Of the original Aquidneck compact signers, five were on the 1655 Newport list: Henry Bull, John Clarke, John Coggeshall, Thomas Clarke, William Coddington. There were seventeen years between the 1638 compact and the 1655 freemen list, and much changed in personal lives and the colonies during that time. Richard Smith is a case in point, having been on the initial Newport list before moving on to Portsmouth, Manhattan, and Cocomcussoc. The other 41 original Newport settlers were also pursuing various vocations and dealing with unique family circumstances – more in the spirit of land use as conceived by the Narragansetts. They were also probably less interested in the new theocracy. However, the settlers’ presence on the island, and in Newport, was also highly influenced by land ownership – and Coddington and his wealthy friends controlled everything. Both, however, knew what a good harbor and active port could do for trade, and realized that Newport was to Portsmouth as Boston was to Plymouth.

Aquidneck Acquisition & Social Implications

There would be no Aquidneck had Roger Williams not suggested it to Coddington or negotiated on the behalf of the Boston exiles. Williams had a vastly different attitude toward Indian lands than all other settlers. The March 24, 1637 deed to Aquidneck was viewed as an outright English legal sale by Coddington, but a right-of-use by Williams and the Narragansetts. The deed itself, witnessed and signed by Williams, said:

“we Cannonnicus and Miantunnomu ye two cheife Sachims of the Narihigansets, by vertue of our generall Command of this Bay, as allso the particular subjecting of ye dead Sachims of Acquednick & Kitackamuckqut, themselves and Lands unto us, have sold unto Mr Coddington and his friends united unto him, the great Island of Acquidneck lying from hence Eastward in this Bay,as allso the Marsh or grasse upon Quinunnagut and the rest of the Islands in this Bay (excepting Chibachuwesa formerly sold unto Mr Winthrop, the now Govr of ye Massachusets, and Mr Williams of Providence) allso the grasse upon the rivers and Coves about Kitackamuckqut, and from thence to Paupasquatah, for the full payment of forty fathom of white beades, to be equally devided between us.”

Just a year later, in June 1638, a few months after the Aquidneck compact was signed, Williams wrote to Winthrop strongly stating that Coddington did not “own” the island in the English sense:

“Sir, concerning the islands of Prudence and (Patmos, if some had not hindered) Aquednick, be pleased to understand your great mistake: neither of them were sold properly, for a thousand fathom would not have bought either, by strangers. The truth is, not a penny was demanded for either, and what was paid was only gratuity, though I choose, for better assurance and form, to call it a sale.”

Regardless, land allocations proceeded on Aquidneck, first at Pocasset and then in Newport. The acreage granted generally matched social standing, particularly in Newport. Those that had earlier settled Newport by 1638 were necessarily displaced by the grants to the nine founding members as only 7 of the 42 on the May 1638 list were on the 1655 Newport list.

Early Aquidneck Island

The original Aquidneck records shed colorful light on island life when it was new to the colonists, and unfortunate for the wolves, foxes, deer, and Indians. The calendar dates in the original documents were based on the Julien calendar, which began the year in March. Therefore, the “20th of the 3d” in 1638 is, under today’s Gregorian calendar, May 20 not March 20. Dates below are presented as recorded in Julien “old style.”

The island’s timeline is as follows (source documents linked in bold italicized dates):

March 24, 1637

Aquidneck deed signed by Narragansett chiefs Canonicus & Miantonomi to William Coddington and friends, witnessed by Roger Williams, who suggested Aquidneck for the Boston refugees, arranged the settlement – but firmly believe that the deed was for use of the land, not literal sale of the island. In June 1638, he wrote to John Winthrop: “Sir, concerning the islands of Prudence and (Patmos, if some had not hindered) Aquednick, be pleased to understand your great mistake: neither of them were sold properly, for a thousand fathom would not have bought either, by strangers. The truth is, not a penny was demanded for either, and what was paid was only gratuity, though I choose, for better assurance and form, to call it a sale.“

March 7, 1638 – Aquidneck compact signed, likely in Providence or Boston, by the followers of Anne Hutchinson. While this is often called the “Portsmouth Compact,” the land they settled at the northern end of Aquidneck was called Pocasset by the Indians. The name “Portsmouth” did not appear in the records for over a year, although it was clearly in use by the settlers as Nicholas Easton’s son, Peter, recorded chronological personal notes in Nathaniel Morton’s 1669 New-England’s Memorial that said “…by the Disention in the Co[u]ntry when Hn Vane was [ ] out from being governor they went unto Road Iland in June and builded at Porch Muth at the Cove and planted there this yeare 1638.” While “Porch Muth” is obviously a phonetic spelling, it does indicate that the settlers referred to the town as Portsmouth by June 1638, two months after the compact.

March 20, 1638

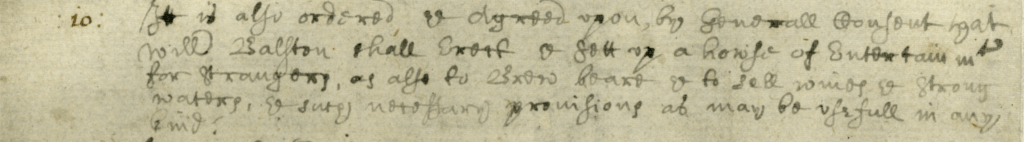

It is also ordered & agreed upon by general consent that Will. Balston shall erect & sett up a howse of entertainment for strangers, & also to brew beare & to sell wine & strong waters & such necessary provisions as may be usefull in any kind.

August 20, 1638

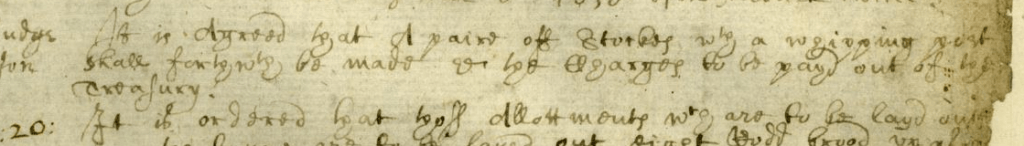

It is agreed that a pair of stocks with a whipping post shall forthwith be made…

June 16, 1639

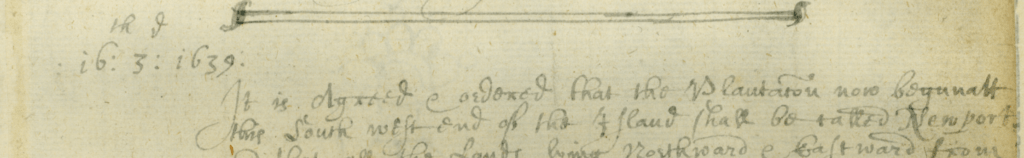

It is agreed and ordered that the Plantation now begun att this South west end of the Island shall be called Newport….It is ordered that the Towne shall be built upon both sides of the spring, and by the sea-side, Southward.

November 25, 1639

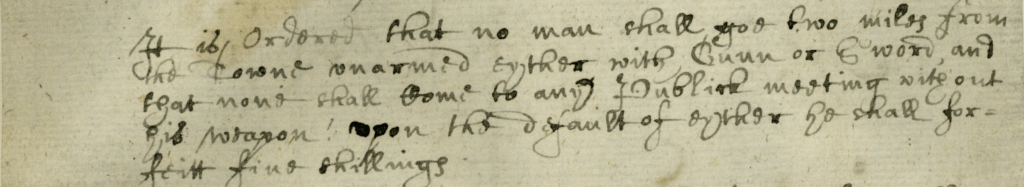

As is ordered that no man shall go two miles from the towne unarmed eyther with Gunn or Sword and that none shall come to any public Meeting without his weapon…

December 17, 1639

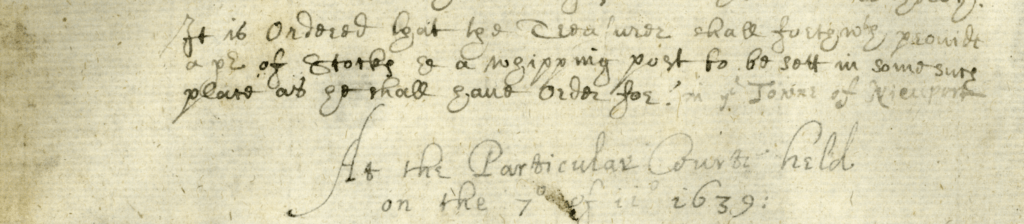

It is ordered that the treasurer shall forthwith provide a pair of stocks and a whipping post to be set in some such place as he shall have order for in ye Town of Nieuport.

March 12, 1640

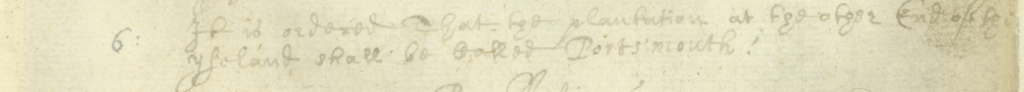

Portsmouth & Newport united to create a single political entity on Aquidneck: It is ordered that the plantation at the other end of the island shall be called Portsmouth.

March 16, 1641

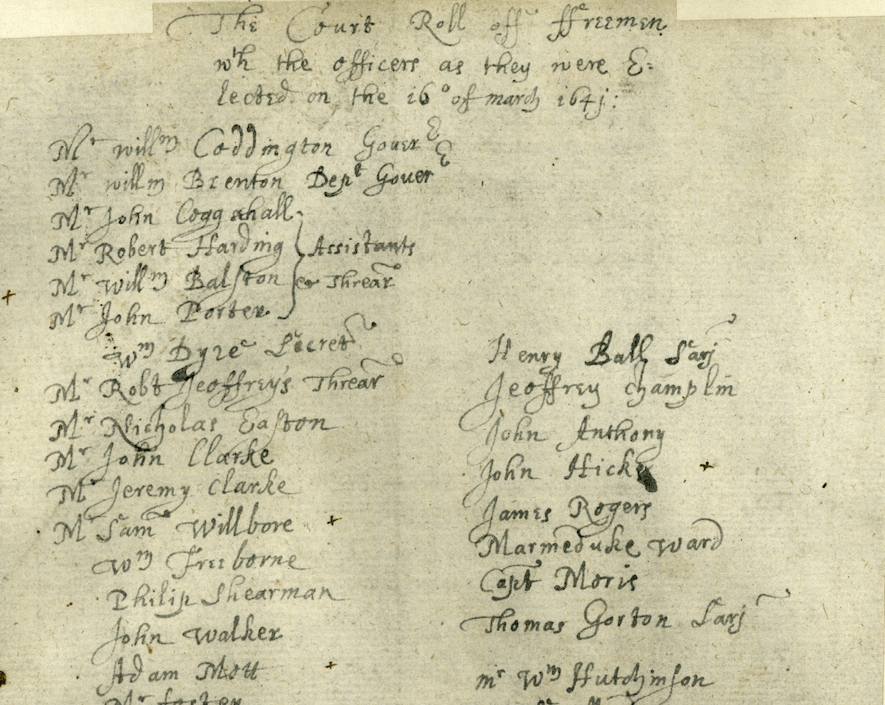

The court roll of freeman with the officers as they were elected on the 16 of March 1641 – Phillip Shearman, Adam Mott

September 17, 1641

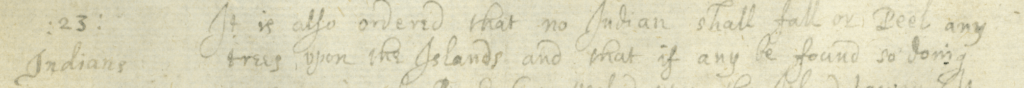

It is also ordered that no Indian shall fell or peel any trees upon the Islands…

September 17, 1641

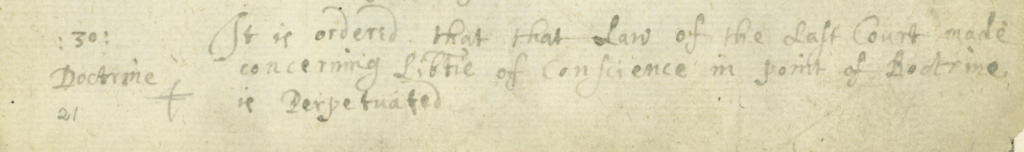

It is ordered that the Law of the last Court made concerning Libertie of Conscience in point of doctrine is perpetuated

March 16, 1642

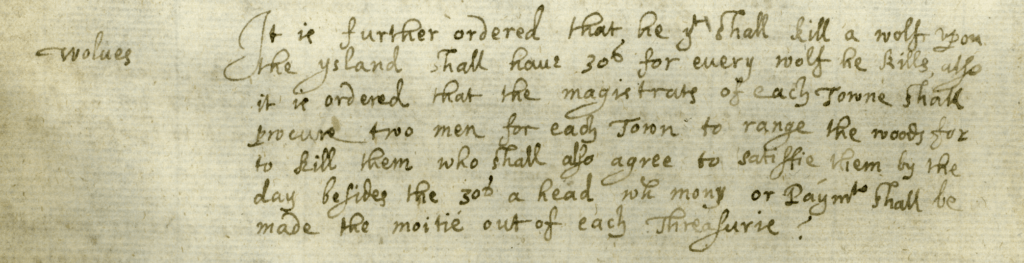

It is further ordered that he that shall kill a wolf upon the island shall have 30p for every wolf he kills, also it is ordered that the magistrates of each towne shall procure two men for each town to rante the woods for to kill them who shall also agree to staisfie them by the day besided the 30p a head with money or payment shall be made the monie out of each treasurie.

March 16, 1642

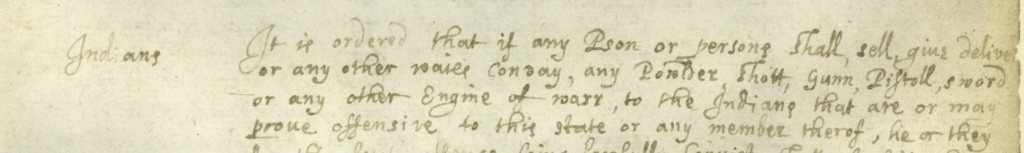

It is ordered that if any person or persons shall sell, give, deliver or any otherwise convey any Powder, Shot, Gunn, Pistol, Sword or any other engine of warr to the Indians that are or may prove offensive to this state or any member of thereof….

September 19, 1642

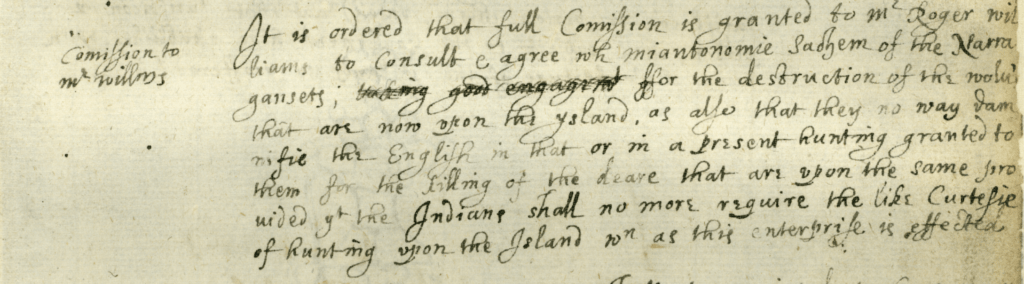

It is ordered that full commission is granted to Mr. Roger Williams to consult & agree with Miantonomie Sachem of the Narragansetts for the destruction of the wolves that are now upon the island. As also that they no way damnifie the English in that or in a present hunting [ground] granted to them for the killing of the deer that are upon the same provided that the Indians shall no more require the curtesie of hunting upon the Island when as this enterprise is effected.

September 19, 1642

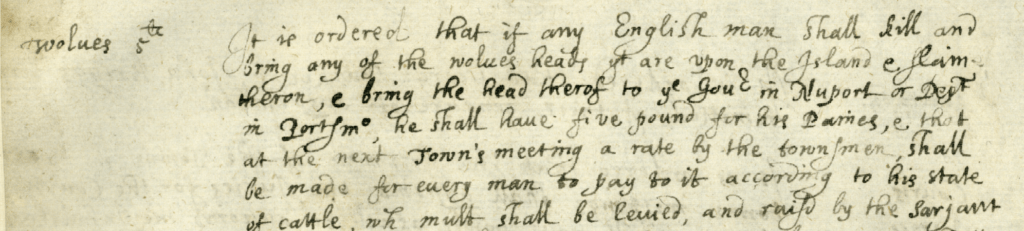

It is ordered that if any English man shall kill and bring any of the wolves heads that are upon the Island and claim thereon and bring the head thereof to ye Govt. in Newport of Dept. in Portsmouth he shall have five pound for his pains, and that at the next Town’s meeting a rate by the townsmen shall be made for every man to pay to it according to his state of cattle

September 19, 1642

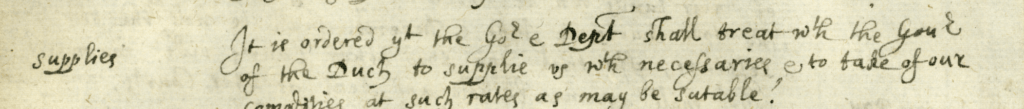

It is ordered that the Govt. Dept. shall treat with the Govt. of the Dutch to supplie us with necessaries and to take our commodities at such rates as may be suitable.