Fortune

1621

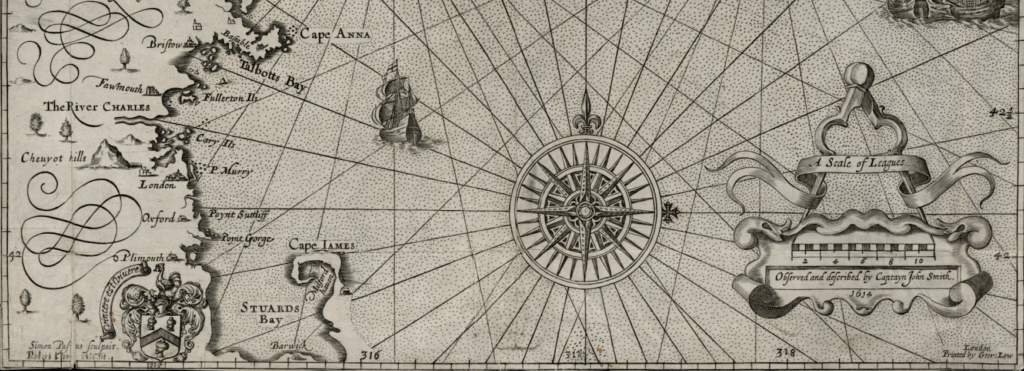

The ship, FORTUNE, was the second English ship to reach the Plymouth Colony after the MAYFLOWER, arriving in November after first anchoring at Provincetown on November 9, 1621. The FORTUNE was 55 tons burthen according to John Smith. At this point in history, tonnage referred to cargo volume and not the ships actual displacement, and was calculated by multiplying keel length by beam by depth of the hold. The specifications of the FORTUNE are best estimated using the plans for MAYFLOWER II and the representative replica of the DOVE, which delivered the first settlers to Maryland in 1634. Both were designed by naval architect and historian William Baker. The MAYFLOWER had a deck length of just over 100 feet and a beam of 25 feet. Pictured above is the DOVE, with a deck length of 54 feet, beam of 16 feet, draft of 6 feet and 42 tons burthen. Using these proportions to FORTUNE’s 55 tons would yield a similar ship of perhaps 57 feet on the deck, 18 foot beam and a draft of 7. Not a very large boat for 35 passengers plus crew. It was likely rigged with a mainmast and a mizzen, which affords a variety of different sail configurations, such as the square main and lateen shown here, with a square sail set under the bowsprit, or a square mizzen for sailing on a run.

FORTUNE’s arrival was a surprise to the pilgrims, but not altogether a pleasant one as half the MAYFLOWER passengers had died and there were not nearly enough supplies either in Plymouth or on the FORTUNE. The three ancestors below arrived on the FORTUNE into the situation described here by William Bradford:

“In November about that time twelvemonth, that themselves came: there came in a small ship to them unexpected or looked for; in which came Mr. Cushman (so much spoken of before) and with him 35 persons to remain and live in the plantation which did not a little rejoice them; and they when they came ashore and found all well, and saw plenty of victuals in every house, were no less glad; for most of them were lusty young men, and many of the wild enough, who little considered whither, or about what they went till they came into the harbor at Cape Cod, and there saw nothing but a naked and barren place; they then began to think what should become of them, if the people were dead, or cut off by the Indians; they began to consult, (upon some speeches that some of the seamen had cast out) to take the sails from the yard lest the ship should get away and leave them there, but the master, hearing of it, gave them good words; and told them, if anything but well should have befallen the people here, he hoped he had victuals enough to carry them to Virginia, and whilst he had a bit they should have their part; which gave them good satisfaction. So they were all landed, but there was not so much as biscuit cake or any other victuals for them, neither had they any bedding, but some sorry things they had in their cabins, nor pot, or pan to dress any meat in; nor over-many clothes, for many of them had brushed away their coats, and cloaks at Plymouth as they came; but there was sent over some Birching Lane suits in the ship, out of which they were supplied; the plantation was glad of this addition of strength, but could have wished, that many of them, had been of better condition; and all of them better furnished with provisions. But that could not now be helped.”

– William Bradford, Of Plymouth Plantation

FORTUNE’s arrival was noted by explorer John Smith, who had spent time already in Jamestown and gave “New England” its name in 1614.

“Immediately after her arrival, from London they sent another of 55 Tonnes to supply them, with 37 persons. The set saile in the beginning of July, but being crossed by Westerly winds, it was the end of August ere they could passe Plimmoth, and arrived at New Plimmoth, in New England the eleventh of November, where they found all the people they left in April, as is said, lustie and in good health, except six that died. Within a moneth they returned here for England, laded with clapboord, wainscot and walnut; with about three hogsheads of Bever skins and some Saxefras…”

– John Smith, New England’s Trials, 1622 edition

Notable in Smith’s 1622 edition is also a letter sent by FORTUNE passenger William Hilton, which is the first mention of “great flocks of Turkies” and, thus, the proof that this fowl was likely served at the harvest that became the Thanksgiving holiday.

Passenger Edward Winslow also mentioned FORTUNE in his publication:

“The Good Ship called the Fortune, which the month of November 1621 (blessed be God) brought us a new supply of 35 persons”

– Edward Winslow, Good News from New England, 1624

Robert Hicks (1578-1647)

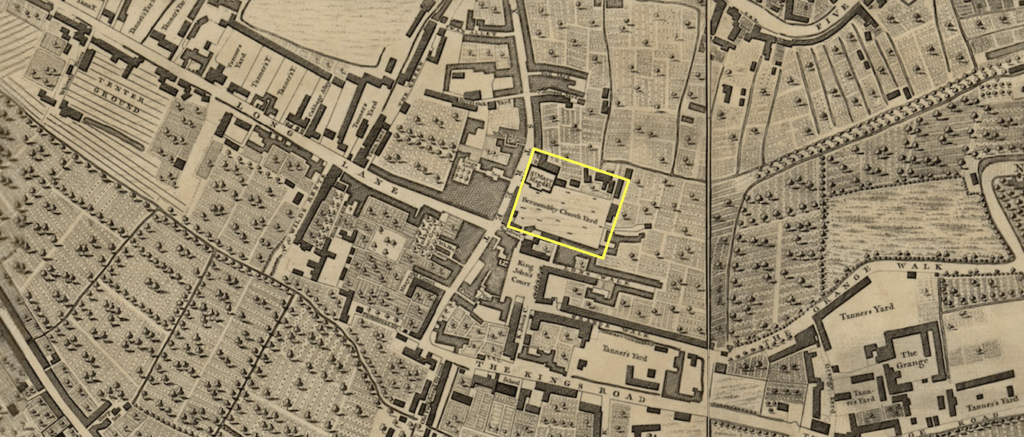

Robert was from London, on the south side of the Thames, in Southwark. Robert sailed alone on the FORTUNE and his wife, Margaret, as well as two children including Samuel Hicks (1611-1677) arrived in Plymouth on the ANNE in 1623. Robert and his family attended St. Mary Magdalen Bermondsey, on a site where a priory was built in the 1080s. Today’s standing church was finished in the late 1600’s and, inside, incorporates original medieval arches. Robert dealt in hides & pelts – a fellmonger – on Barmundsey Street. In a legal deposition, it was said that “Robte Heeks did pull three hundred pelts a week and diverse times six or seven hundred & more a week in the killing seasons, which was the most part of the year (except the time of Lent) for the space of three or four years. And that the said Robte Heeks sold his sheep’s pelts at that time for 40s. a hundred.”

It’s difficult to overestimate the extraordinary demand for leather before industrialization and modern materials. A fellmonger prepared the skin (or “fell”) by removing hair, wool and other bits to produce the rawhide, which would then move on to a tanner to dress it into leather with bark tannin, and a currier to finish it. The entire industrial process was quite a mess, and was prohibited within London, while the nearby pastures and river water supply in Bermondsey were ideal. This is clearly seen in the 1690 map of London by Johannes De Ram, with St. Mary Magdalen alone in the fields to the southwest. The adjacent 1746 map of London by John Rocque shows the tanning industry located very much around St. Mary Magdalene before it migrated northwards up the street in later industrial years. A “Fellmongers” path in the 1746 map was right off Bermondsey on the west side of the street before the junction of Snows Fields and Crucifix Lane, then as now. The large skin market in 1746 was to the west in Bankside, right on the Thames. To go to the skin market, Robert would have walked right by Shakespeare’s theatre, the Globe, and perhaps Shakespeare himself (1564-1616). Bermondsey Street roughly parallels todays Tower Bridge Rd. I visited St. Mary Magdalen and walked Bermondsey and Bankside in February 2024. Even today, the leather history is embedded into street, pub and restaurant names: Fellmongers Path connects to Tower Bridge Road across from Tanner Street, which crosses Bermondsey into Leathermarket Street.

Thomas Prence (1600-1673)

Came as a single man and, in 1624, married ancestor Patience, daughter of MAYFLOWER passenger William Brewster, who came on the ANNE in 1623. Patience died in 1634 of a fever. Thomas was an assistant of William Bradford, and became Governor of the colony himself, serving two terms in 1634 and 1638. Also aboard the ANNE with Patience Brewster were Robert Hicks and his family, as noted ablve, as well as Nicholas Snow, who married Constance Hopkins whose father, Stephen, had already arrived on the MAYFLOWER.

Stephen Deane (1606-1634)

Came as a single man. Stephen owned and operated corn mills for the town of Plymouth. He married Elizabeth Ring and they had three daughters. Daughter Elizabeth, an ancestor, married William Twining and their daughter, also Elizabeth, married Joseph Rogers, son of Joseph Rogers and grandson of Thomas Rogers, both MAYFLOWER passengers.