John Cornell

unknown-1758

A redcoat in the 44th Regiment of Foot, John Cornell survived the Battle of the Monongahela on July 9, 1755 and died at the Battle of Carillon (Ticonderoga) on July 8, 1758. These were easily two of the most important events – and horrendous defeats – of the entire French & Indian War.

It has taken quite a bit of work to make this statement about John as there is no surviving military documentation in which John Cornell appears, nor have any records yet surfaced in the United Kingdom. Regardless, with the help of military historians, authors and some new sources, I’ve been able to put some facts alongside the family story. The brief outline of events that has been passed down was also published in a newspaper article from the town in which John Cornell’s son, William, settled after the Revolutionary War:

“John Cornell, the father of William Cornell, Sen., was an officer in the British army in the French war. His regiment was stationed for a time in the city of Dublin. He was married during the time, and his son William was born during his stay there. William was two years old when his father came to America to take part in the French war. John Cornell fell at the storming of Fort Ticonderoga, under Abercrombie.” YATES COUNTRY CHRONICLE, VOL XXVII NUMBER 13, THURSDAY MARCH 31, 1870, PENN YAN, YATES COUNTY, NEW YORK

One particular problem with the timing in this statement regarding John’s sailing when William was two years old is that England wasn’t technically at war with the French in 1752. John’s story was also captured and passed along in a family tree prepared by John’s great-great grandson, George Rathbun Cornwell, and military and local historian, Walter Wolcott, a descendant of Declaration signer Oliver Wolcott. With this background, and a working knowledge of the French & Indian War, I hired a military researcher in the United Kingdom to physically go through actual muster books in the National Archives in Kew, England. Unfortunately, the relevant muster books for the regiments engaged in America at that time are generally lost, and other related records turned up nothing. In my mapping of all the regimental movements that would fit the family story, I was helped by, and corresponded with, author Stephen Brumwell, author of Redcoats – The British Soldier and War in the Americas 1755-1763. A pivotal turn in the research occurred when I attended an annual book award dinner and lecture of the Society of Colonial Wars in the State of New York. The presentation was by author and historian, David Preston, on his amazing book, Braddock’s Defeat – The Battle of the Monongahela and the Road to Revolution. We spoke that night, and I took home a copy of his book, eager to dive in. I had only made it to page 57 when I froze on footnote 34, which described specific numbers for troops drafted into the 44th Regiment of Foot while in Ireland. What I had not focused on previously was the “Irish Establishment.” Beginning in 1749, the British army was garrisoned in Ireland during peacetime and rotated to various barracks.

I then found two old pamphlets called “The Quarters of the Army in Ireland, 1749” and “The Quarters of the Army in Ireland, 1752.” Knowing that John died at Ticonderoga narrowed his possible regiment to those present at the battle: the 27nd, 42nd, 44th, 46th, 55th, 60th, and 80th Regiments of Foot, the 4th and 17th artillery companies, and independent companies of rangers and provincial militia. The challenge, however, was the potential route that each of those regiments took to arrive at Ticonderoga. The 60th and 80th were created in America. A presence in Dublin is critical because about 275 days before William was “born in Dublin,” John Cornell would have to have been conceiving him. When the 27th & 42nd sailed for New York in 1756, William would have been six years old. That has little correlation with the “two years old” statement and, more importantly, we know that John served “under Abercrombie” who led the 44th in America, which triangulates John to the 44th (XLIV). The next step was to confirm that the 44th was actually at the Dublin garrison when John was to have been conceiving William. Fortunately, I came across a footnote in an article that led to my contacting an organization based in England, the Society for Army Historical Research, which mailed me a copy of pages from their Summer 1994 journal (Vol LXXII No. 290). It precisely documented where the 44th moved while in the Irish Establishment. More importantly, it described the process by which the army made an annual rotation in the spring or early summer of the year to a new location in Ireland. This was the key. The 1749 pamphlet showed the 44th in Dublin. The Society’s journal showed that, in the spring of 1750, the 44th moved out of Dublin and sent four companies to Gallway, three companies to Newport, and 3 companies to Ballinrobe. In 1751, they were in Limerick. In 1752, they were dispersed to Cashel, Youghal, Dungarvan, and Nenagh – which corresponds to the 1752 pamphlet. In 1753, according to the Society’s journal, they were in Cork, where they remained until departing in 13 transport ships on January 14, 1755 for America, with Braddock personally aboard Commodore Augustus Keppel’s CENTURIAN. Thus, John was garrisoned in Dublin through the spring of 1750. If William’s birthday was October 19, 1750, he had to have been conceived around January 9 through January 23 – and John was garrisoned in Dublin at this time. William still would have been “two years old” in the Spring of 1753 when John left for Cork. While this is not his actual sailing date for America, it was certainly his leaving to assemble at the final port of embarkation, and fits the general “when he was two” timeline which, itself, may be a generalized error of recollection.

Monongahela

While the story of John Cornell has always both started and finished with his death at Ticonderoga, this new information places him squarely in Braddock’s fleet to Virginia, arriving February 20, 1755, and Braddock’s disastrous march to Fort Duquesne at the confluence of the Monongahela and Allegheny rivers, at what is now Pittsburgh.

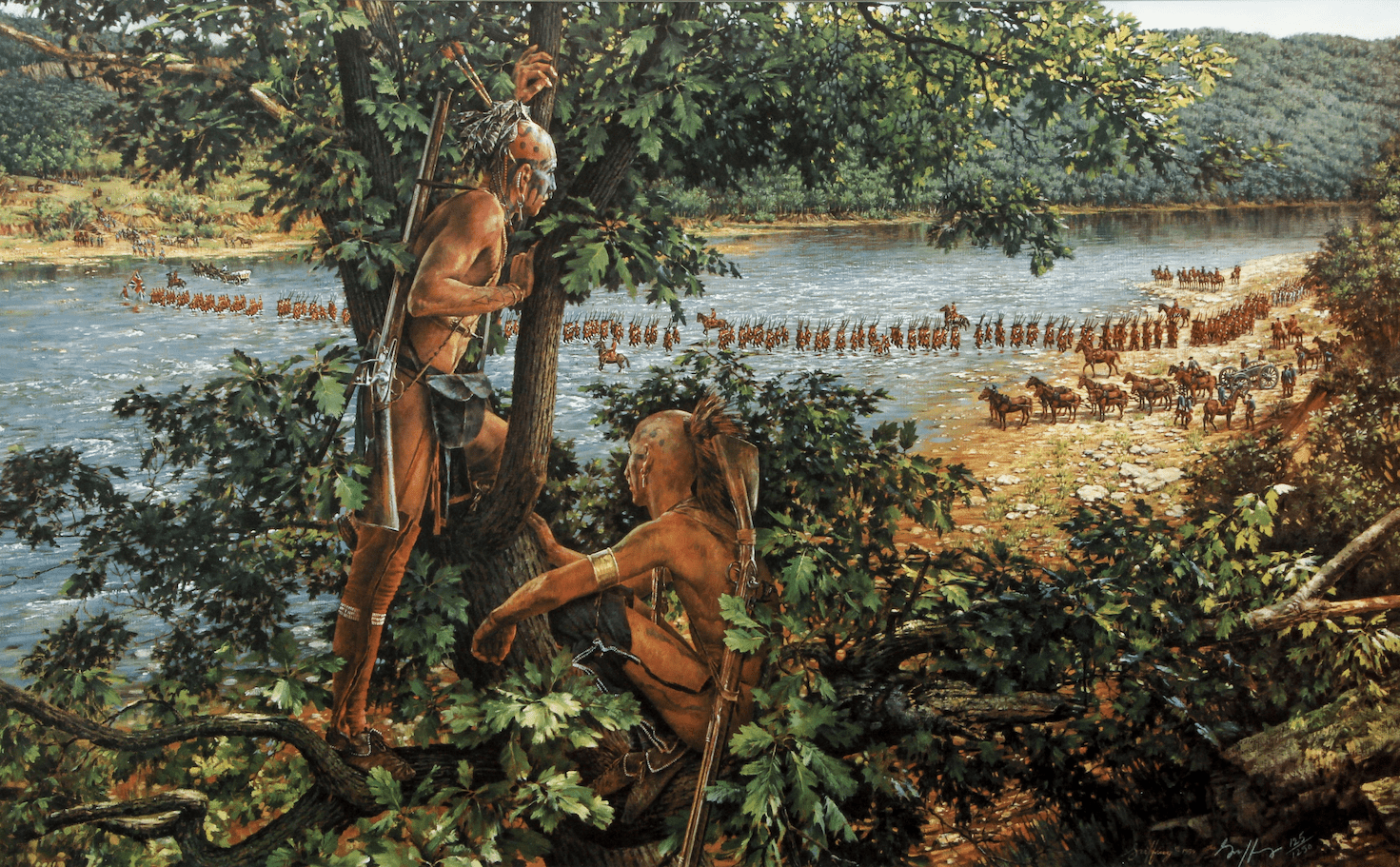

David Preston’s, Braddock’s Defeat, is a thorough, original, and engaging picture of the July 9, 1755 French & Indian ambush in a wooded ravine (a scenario that would repeat itself later at Oriskany in 1777). George Washington was there to witness the carnage, along with Daniel Morgan, Daniel Boone, and others who would end up involved in the Revolution (Gage, Gates, Lee). Nearly 500 of 1,300 were killed and another 400 wounded. A good account is also given in Historical Record of the Forty-Fourth, or the East Essex Regiment, by Thomas Carter in 1887 in which the wounded officers are named. In both accounts, it is clear that the 44th was exposed to the entire action, with grenadiers and battalion companies in the advance company of the order of battle, and the remaining battalion companies dispersed through the main body and the rearguard.

North to New York

After the slaughter at Monongehela, and the retreat under Col. George Washington, the 44th reorganized in Philadelphia. Major-General James Abercrombie was appointed Colonel of the regiment on March 13, 1756. The regiment was in Albany in August 1756, was concentrated in New York City in June 1757, and then dispatched to Halifax for an expedition against Louisbourg (Cape Breton Island, Canada), and returned before winter. In 1757, James Abercrombie also became the commander in chief of North America and the army was divided into three campaigns: 1) Jeffery Amherst to Louisbourg; 2) John Forbes to Fort Duquesne; and 3) James Abercromby to Ticonderoga.

There’s some family correspondence I have found about John that mentions Halifax. Perhaps William may have heard that John had been in Halifax – or possibly received a letter – or perhaps this was conjecture by the author in the early 1900s in the absence of the records we possess today. I think the timeline presented here shows how he managed to be in Halifax prior to Ticonderoga; it does not fit with the record of troop movements that he sailed from Ireland to Halifax. There were other regiments that sailed directly for Halifax, like the 47th, which had been in Dublin in 1749, but was not at Ticonderoga. Also, there was not widespread movement between regiments, and supplemental recruiting generally came from the surrounding population.

Ticonderoga

Carter’s Historical Record gives good account of the 44th action at Ticonderoga (Fort Carillon) on July 8, 1758, which makes it clear that “no separate return of casualties has been preserved.” The action is also thoroughly covered in Fred Anderson’s 2000, Crucible of War. I walked the grounds during the 250th reenactment in 1998 and it reinforced the desperation of the attempt against the French position. And I knew that, somewhere on the grounds, John Cornell was buried.

The 44th and the rest of Maj. General James Abercromby’s army left Fort William-Henry on July 5, 1758 and sailed up Lake George in 900 bateaux and 135 barges. The 44th Foot numbered 850 men all ranks, and the total number of British regulars was 5,825. Combined with 11,785 American auxiliaries, provincials and Indians, the total force was around 17,600. They landed in the early light of July 6 at the northern head of the lake. When one thinks of Fort Ticonderoga and its mighty star-shaped walls high up on a precipice over the lake, it’s easy to imagine that this is where the fighting happened. Although the fort commands the point, the battle was at the western approach to the peninsula. It’s here, at the top of a steep slope, that the French built lines of trenches, earthworks, log walls and an “abbatis” of felled trees with branches cut and made pointed. According to Maj. General the Marquis de Montcalm, the slope was steeper on the French left than the right. The French camouflaged all of this from the English scouts, which contributed significantly to the decision to attack. The French force was just 4,200 men. On the morning of July 8, Abercromby organized the force for a classic frontal attack led by skirmishers then provincials – including rangers with John Stark and Robert Rogers, followed by the regulars to storm the defenses. At the outset of the attack, the 44th was in the center brigade under Lt. Col. John Donaldson. A mistaken charge of regulars in the left brigade (27th and 60th) was swallowed up by the abbatis, where they became easy targets. As order broke down amongst the abbatis chaos, Abercromby did not try to outflank the defenses or wait for artillery. Around 2pm, the 44th and 42nd moved to the right to outflank the French left, approximately where the red mark is in the adjacent maps. The right image is a fascinating LIDAR view of the French Lines, in which the steepness of the French left is quite clear. It’s understandable how an assault up this slope could end in disaster.

They encountered the militia volunteers of Capt. Duprat, of the Bearn regiment, and Capt. Bernard, of the La Serre regiment, and the Royal-Roussillon regiment – all of whom had been posted on the left edge of the entrenchments nearest the La Chute river. The La Serre regiment, in the entrenchments, put the British in a crossfire, driving them to retreat. It is here, in the abbatis, that John Cornell likely died. If not, then it was in continued British assaults into the late afternoon, mainly on the French left and center, which culminated with the attack of the 42nd Highlanders around 5pm. After other futile attempts, the British retreated the field at 7pm. The British lost nearly 600 men. Many of the dead were never buried. Years later, in the winter of 1775-1776, Ethan Allen left 1,000 men garrisoned at the fort, some of whom built crude shelters near the French defenses, about which Col. Anthony Wayne called “the last part of God’s work, something that must have been finished in the dark…ancient Golgotha or place of skulls – they are so plenty here that our people for want of other vessels drink out of them whilst the soldiers make tent pins out of the shin and thigh bones of Abercrumbies men.”

Other Matters

The claim that John Cornell was a “captain in the British army” cannot be documented. There is no record of it in England and, if the commission happened in America, the loss of records provides no support. How did William know that his father, John, died at Ticonderoga and was a captain? There are only two possible answers. Perhaps a letter, or letters, from John were sent back to Dublin, which assumes that he could write. Alternatively, news of his death was carried back through official channels of the 44th or perhaps from a colleague of John’s that returned to Dublin to deliver the news. In terms of composition, in 1749 the 44th in Dublin had 10 companies and 374 soldiers in total. The officers of the 10 companies included Col. John Lee, Lt. Col. Sir Peter Halkett, Major Hon. Thomas Gage, and seven Captains – Tatton, Chapman, Kennedy, Ayers, Hobson, Hardwicke, and Bromley. That same return in 1752 saw Chapman made Major in the absence of Lee, and Beckwith appointed as a new Captain. Under each of them were one lieutenant and ensign. The officers also included a chaplain, adjutant, surgeon, and surgeon’s mate. Subtracting these four from the total, the 370 soldiers were distributed as 37 to each company; with three officers each, that left 34 privates. Perhaps there was a reorganization or promotion prior to the battle, and somehow this news made it to William and Anna; we will never know.

The name of John’s wife, and William’s mother, was most likely “Anna” knowing that the naming conventions of the day typically drew from the father and mother’s side. William Cornell’s wife was Hannah Finch, from Greenwich, Connecticut. Her parents were Jeremiah Finch and Abigail Rundle; her grandparents were Samuel Finch, Mary Whelpley, Abraham Rundle, and Rebecca Mead. It’s likely that William did not know his family tree, and it’s likely that Hannah knew hers in detail as her family had been the founders of Greenwich and Stamford. William and Hannah named their children, in order: 1) John 2) Anna 3) Rebecca 4) Samuel 5) Mary 6) William 7) Hannah 8) Abigail 9) Elizabeth 10) Phoebe. The first two were likely the names of William’s parents, and the rest are documented in Hannah’s family. While it would appear likely that John’s father was also named William Cornell, William Cornell’s son, William, changed the spelling of the family name to “Cornwell.” Perhaps he learned something about John or Anna that drove this decision. The “w” in English when mid-word is often dropped in pronunciation, as in “Greenwich” so the phonetics of “Cornell” and “Cornwell” were similar at that time, as distinct from modern day American. Until a record is uncovered in England or Ireland, we cannot know. We also don’t know the circumstances of John’s meeting “Anna.” Similar to a scene in a painting by John’s contemporary, David Morier, soldiers would have been out and about through the town in which they were garrisoned. The Dublin marriage record of John and Anna has not yet been found, and neither has William’s baptism. Since William was a Protestant, as was the army at large at that time, it is likely that John was as well. There is a reference in the family story to Anna making lace. This could possibly indicate that she was a Huguenot, who were experts in textiles and had settled in Dublin. By the early 1700’s, Dublin had a large French Protestant population with four Huguenot churches. Assuming that John was not from Dublin, it’s likely that the marriage and birth of William would have occurred in one of the Protestant churches in Dublin. It’s also interesting to note that Greenwich, Connecticut – where Hannah was from – is only 12 miles along the coast to New Rochelle, New York, which was settled in 1688 by French Huguenots. Possibly, this helped draw Anna and William to America when they came in 1765.

Finis

Until his bones are found on the grounds of Ticonderoga someday, or heretofore unseen documents are produced through research, this is all we can know about the enigmatic John Cornell.