Andries Luicasz

1620's

Andries was amongst the first to sail to, and live in, what became New Netherland. He was likely a crew member of the early trading and exploratory voyages and may have spent time at one of the trading posts for an extended period before the colonists arrived in 1624. He was born around 1595, likely in the area between the Netherlands and the German/Danish Jutland peninsula. Andries was a sailor, appearing in 1638 as upper boatswain on the KALMAR NYCKEL to establish New Sweden, then in further records as a 1648 “skipper” in the Delaware Bay and sailing on Long Island Sound. His son appears in prolific New Netherlands records as a sailor, yacht owner, and with a Manhattan residence at what is now 13 Broadway.

December 29, 1638

Affidavit of KALMAR NYCKEL Crew. “…appeared personally in the presence of the witnesses named below, before me Peter Ruttens, the residing public notary in the City of Amsterdam, admitted and sworn by the Supreme Court in Holland…lately served on the ship called the Key of Calmar, and have come with her from the West India to this country…. together with the director Peter Minuit, the skipper Johan von de Water and the former upper boatswain Andress Lucassen and still other officers of the Ship’s-council, were on this ship, and an examination was made by order of the honorable Mr. Peter Spiring, Lord of Norsholm, financial councilor of the worshipful crown of Sweden, and resident of the same in Hague…appeared and presented themselves before the abovementioned ship’s council, in the name of their nations or people, five Sachems… because, however, they did not understand our language, the abovementioned Andress Lucassen, who had before this lived long in the country and who knew their language, translated the same into their speech.”

Peter Minuit went with his family to New Amsterdam in 1625 and became Director General in 1626, a position he held until 1631. He returned to the Netherlands in August 1632, where he took his knowledge of the new world to the government of Sweden. The Swedes, under Queen Christina, were more than happy to employ him in their establishment of a colony in what is now Delaware, then called the “South River.” Although the Dutch claimed the land, Minuit sought to leverage a legal loophole of Indian land ownership. KALMAR NYCKEL (“key of Kalmar”) was a merchant pinnace converted to a warship and sent to America in 1638 to negotiate with the native Americans for the land. Minuit and Andries were aboard, as well as captain Jan Hindricksen and soldiers – but no colonists. Not only was Andries a sailor, but he was fluent in Algonquin which would be critical in the land negotiations. They arrived in late March 1638 on a western shore tributary of the Delaware river at what is today called Swede’s Landing. Five Indian sachems boarded the ship on March 29, 1638 and a deed was drawn up through Algonquin interpretation by Andries. A small fort was erected, and the KALMAR NYCKEL left by June, bound for the Caribbean for trading before sailing back to Sweden. In the harbor of St. Christopher, just to the north of Nevis, a hurricane struck. Minuit had gone aboard a neighboring Dutch ship at anchor in the harbor, the FLYING DEER, and was killed in the storm. After stopping for repairs in the Netherlands, the KALMAR NYCKEL made it back to Sweden. It returned with colonists on April 17, 1640 and in two subsequent voyages to “New Sweden.” It’s unknown whether Andries was on these later voyages, or how he ultimately came – with his wife and children – to New Netherland. New Sweden ultimately fell to Peter Stuyvesant on September 15, 1655 and became “New Amstel.”

The fact that Andries, in 1638, was in Europe yet fluent in Algonquin, suggests that he had spent a considerable amount of time in America prior to this date – not just sailing, but as the affidavit says, he had “lived long in the country.” It is likely that Andries participated in one, or multiple, early trading voyages to New Netherland, where he acquired local knowledge, navigation, and language. Roger Williams arrived in Massachusetts in 1630 aboard the LYON and published his native Algonquin dictionary, the first, in 1643 – thirteen years later. It would not take this long to be conversational in a completely foreign language, but it would take some time to reach the proficiency required for the nuances of statecraft.

Andries could have been at sea as a young boy, or certainly by age 18, in 1613, only a few short years after Henry Hudson, under the authority of the Dutch East India Company, sailed past Manhattan in 1609 in the HALVE MAEN (“half moon”) and went up as far as present Albany. A record dated May 2, 1611 in Amsterdam names the command of a subsequent HALVE MAEN voyage to Melis Andries, although it’s unknown if this is the same family. 1611 saw additional voyages to America, including Adriaen Block & Hendrick Christiaensen, who brought two Indian brothers back with them to Holland. Then, in 1613, they returned again, including the Indian brothers, with Adriaen Block sailing on TIJGER (“tiger”) and Hendrick Christiaensen on FORTUYYN (“fortune”). The ships left in June and reached the Hudson by summer. Block stayed near Manhattan, anchored where present day Greenwich & Dey streets intersect, and where TIJGER’s timbers have been found. Christiaensen went up the Hudson to build and name Fort Nassau on Castle Island at present Albany. The TIJGER caught fire and Block and his crew spent the winter on Manhattan building a new boat, the ONRUST (“restless”) out of the old timbers. In the Spring of 1614, Block sailed east out Long Island Sound, the first to do so, and thus record Manhattan as an island. He sailed up the “Fresh River,” now Connecticut, as far as present Hartford, and named Block Island after himself as he headed eastward toward home. The FORTUYYN left Fort Nassau when the ice thawed, with crew left behind to man the post. Block boarded the FORTUYYN near Cape Cod and sent crew to further explore the South River. Had Andries wintered on Manhattan, or sailed to and from Holland with two native Americans, he certainly could have become proficient in their language.

During this period, several other ships went to the same regions on exploratory missions. To simplify trading, the States-General created the New Netherland charter on October 11, 1614, based on the “Nieuw Nederlandt” that Block had put on his map. It wasn’t until 1621 that the Dutch West India Company was formed and the first ship with settlers, the EENDRACHT (“unity”), sailed in 1624 under captain Adriaen Joriszen Thienpont. The second was the NIEUW NEDERLANDT in 1624 under captain Cornelis Jacobszen May with 30 families – some of whom went to the Fresh (Connecticut) and South (Delaware) rivers, some to Nut Island (“Governors”) off Manhattan, and the bulk to Fort Nassau, which May rebuilt into Fort Orange. Andries could have been on these or numerous ships in subsequent years.

That Peter Minuit chose Andries for the immensely important work of New Sweden implies that he’d known him while he served as Director General on Manhattan from 1626-1632. For Andries to display impressive knowledge of Algonquin during this timeframe means that he was likely living there beforehand, or at least near the outset of settlement. Coupled with the 1638 statement that Andries had “lived long in the country,” this implies that Andries was probably living here in the late 1620’s at Fort Orange or Fort Amsterdam, amongst the first to inhabit New Netherland. It’s also possible that Minuit chose Andries for the extremely important negotiation in Delaware because Minuit had personal experience with Andries previously in New Netherland and, more specifically, in Minuit’s Spring 1626 purchase of Manhattan from the Indians. The adjacent picture, taken by me, is of the original November 5, 1626 letter describing Minuit’s “purchase” of Manhattan. Language and diplomacy were everything in such a situation, and years of trading with, and living amongst, the Indians would have made Andries the perfect choice, on more than one occasion.

Andries could also have been amongst the interpreters working with Kiliaen van Rensselaer on his land purchases:

January 10, 1630

“for Bastiaen Ianssen Crol, commis at Fort Orange, who if he sees fit may call to his assistance Dirck Corneliss, his onder-commis, and such other persons as he shall think best and advisable. First, Crol shall try to buy the lands hereafter named for the said Rensselaer, from the Mahijcans, Maquaas or such other nations as have any clame to them, giving them no occasion for discontent, but treating them with all courtesy and discretion.”

This does not indicate that Bastian Jansz Krol or Dirck Coornelisz Duyster, themselves, were fluent as interpreters – but that Krol was to employ “such other persons as he shall think best and advisable.”

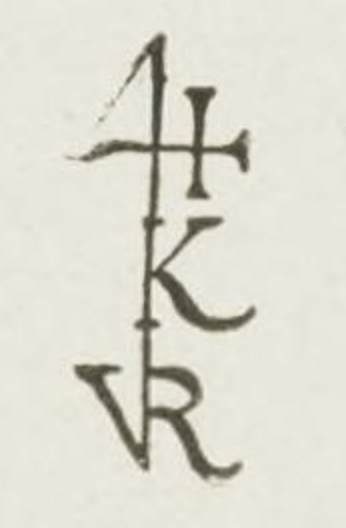

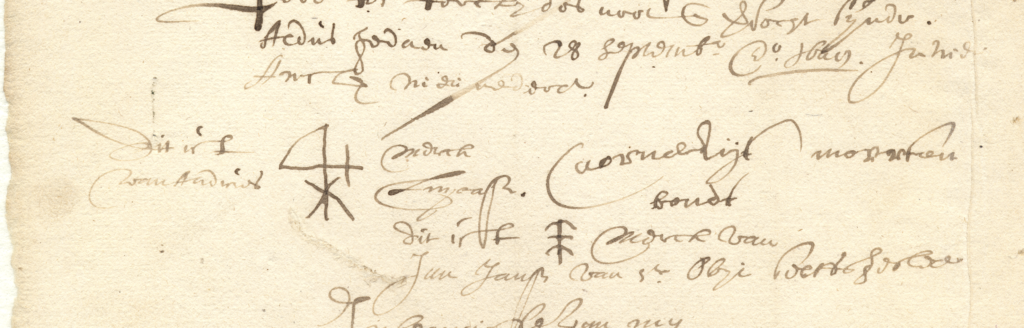

Andries signed his name with a mark, an indication that he could not read or write, beyond perhaps that needed for maritime navigation. Andries’ mark is very interesting in its extreme similarity to Kiliaen van Rensselaer’s marks for his trade and for the colony. When corresponding personally, Kiliaen signed his name in full, with flourish, but with no marks or devices. His mark for Rensselaerswyck was a “4” and “+” above a “R” and “W” done in the style of the Dutch West India Company. Kiliaen’s merchant mark for commerce is the same upper “4” and “+” but atop his initial “K” and a combined “VR”. Both of Kiliaen’s marks incorporate the “4” device. While no mainsails were rigged and cut like that in the 1600’s, it does show the shape of forward sails. This device certainly would have appealed to Andries, who applied it above a traditional “X” mark, but he carried the vertical/mast line down through the center of the “X” as if to anchor it, like a ship. The mark also indicates that Andries identified with the oldest part of New Netherland – Fort Orange/Fort Nassau. Although records are lost, it would be interesting if the device itself had existed in the Fort Orange records and was, for this reason, originally adopted by Kiliaen above his own “KVR.”

A marriage record has not yet been found for Andries and his wife, Jannetje Jans, either in America or the digitized Amsterdam archives. Andries’ last name means “son of Lucas” but is spelled variously in Dutch records as “Luicasz,” “Luijcasz,”and “Lucasz.” The available records indicate that Andries & Jannetje came early to New Amsterdam and there had three of their recorded children – Marritje, Lucas, and Geerturyd – within the span of Pieter Minuit’s 1625-1632 directorship. Later records confirm that Marritje and Lucas were born in New Amsterdam, and the marriage record of Geerturyd places her birth there as well. At some point before 1633, Andries and Jannetje moved back to Amsterdam where records for four children – Annetjen, Jans, Pieter, Berber – are found in the Amsterdam archives from January 1633 through September 1641. It is during this time that Andries sails on the KALMAR NYCKEL, returning to Amsterdam by 1639 after its first voyage. The September 10, 1637 baptismal record of their son, Pieter, noted that Andries had gone to the West Indies, as all of America was known, and the trade winds would naturally carry a ship first to what we today call the West Indies before sailing north to the American colonies. Without modern communication, this statement makes sense because Andries would have already left to meet the ship in Gothenburg, Sweden, which it sailed from in December 1637. During this time back in Amsterdam, Andries had missed the New Amsterdam directorship of Willem Kieft. Sometime before 1647, Andries & Jannetje move back to New Netherland, where two daughters – Marritje & Geertruryd – are married in 1647 and 1648. Andries appears in the New Netherlands records witnessing the baptism of his granddaughter in 1648, the same year he is also in the records giving depositions to Tienhoven.

In the New Netherlands records, patrynomics show Andries’ children in various forms as “Andrieszen,” “Andries,” “Lucas,” “Lucassen” or “Luycassen.” Somewhat of a mystery is the appearance of “Sebyns” after Jannetje’s name. It exists nowhere in the Amsterdam records, and even a Google search applies it to Jannetje in the top results. Without seeing the original script in the New Netherlands baptismal book, it is either a mis-transcription, or it was applied to her because there were to many other “Jannetje Jans” and someone asked her what her father’s name was – and it was likely “Sebastien,” and “Sebyns” being a shortened form of patronymic. Regardless, the name was never used again and the naming conventions of all Andries & Jannetje’s children and grandchildren honor both of their names. The date of his death, and that of Jannetje, are unknown.

Upon settling permanently in New Netherland, Andries remained a sailor, as seen in two records below. The September record is interesting as it places Andries sailing the length of Long Island Sound in the fall of 1647, which is also in the decade that Richard Smith was trading between Manhattan and Narragansett Bay. On this particular trip, he was as East as Gardiner’s Bay between the north and south forks of Long Island, was up the Pawcatuck river that separates Rhode Island from Connecticut between Watch Hill and Stonington, respectively, and to New Haven. Govert Loockermans’ bark was the GOOD HOPE, which he purchased from Isaac Allerton. Govert also had a brewery on what is now Pearl Street, and was certainly a friendly contemporary of Richard Smith, who lived down the road and also traded with Allerton. This record also establishes his date of birth as 1595. The November record places Andries back down on the Delaware river at Fort Beversreede, a trading post located where the Schuylkill and Delaware rivers meet.

September 28, 1648

Before me, Cornelis van Tienhoven, secretary of New Netherland, appeared Andries Luycassen, aged 53 years, Cornelis Mauritz Bout, aged 33 years, and Jan Jansen from St. Obyn, aged 27 years, who at the request of Mr. Govert Loockmans attest, testify and declare, in place and with promise of an oath if necessary, that it is true and truthful that in the months of October and November, etc., Anno 1647, they sailed with Govert Loocmans and his bark along the north coast from New Amsterdam to Pakeketock [Watch Hill], Crommegou [Gardiner’s Bay] and New Haven, during which voyage aforesaid they neither saw nor heard, nor even knew, that Govert Loockemans himself, or any of his crew, directly or indirectly traded or bartered with the Indians there or elsewhere any powder, lead, or guns, except that he, Loockmans, made a present of about one pound of powder to the chief Rochbou in the Crommegou and purchased two geese in the Crommegou and half a deer at Pakatoc with powder, without having given to or exchanged with the Indians anything else to our knowledge. The deponents declare this to be true and offer to confirm this by oath if necessary and required. Thus done the 28th of September A°. 1648, in New Amsterdam, New Netherland. (original & translation)

November 4, 1648

We, the undersigned declare and attest by Christian words and on our conscience in place and under promise of an oath, if it should be needed, that it is the truth and nothing but the truth, that we have demanded from the Swedish Lieutenant his commission and orders, which he has shown us from his Governor, wherein it was expressly stated, that he should not allow any post or stake to be set in the ground and in case such were attempted to be done, to prevent us by friendly words or by force; his instructions also being, to keep continually two men in the channel, to see, where we would build and not let any building timber be landed. The 4th 9bre 1648, at Fort Beversreede. – Alexander Boyer, David Davitsen, Adriaen van Tienhoven, Piter Harmansen, This is the mark of Symon Root (S.R.), This is the mark of Andries Luycassen, Skipper (4xt) Agrees with the original, Sign. Cor. Van Tienhoven, Secretary (original & translation)