New Netherland

Buried, but not lost, in history is the extraordinary role that the New Netherland colony played in the birth of America. The Dutch way – tolerance, free trade, liberty – contributed to essential American foundations. The Dutch did not have a monopoly on these ideas in the old world, or even the new: both Jamestown (1607) and Plymouth (1620) were commercial enterprises, and Roger Williams in Rhode Island wrote about freedom of religion and the separation of church & state long before the 1657 Flushing Remonstrance. The uniqueness of New Netherland remained when it was renamed New York, and it remains today: an incredibly diverse population driven by commerce. The physical product of this – the gridded skyscrapers of modern Manhattan – lies in perfect contrast to the marshy banks and rolling hills of the primordial island it once was. It is here, at the very beginning, that records provide a fascinating look at the physical and social presence of some early family, links for which are below.

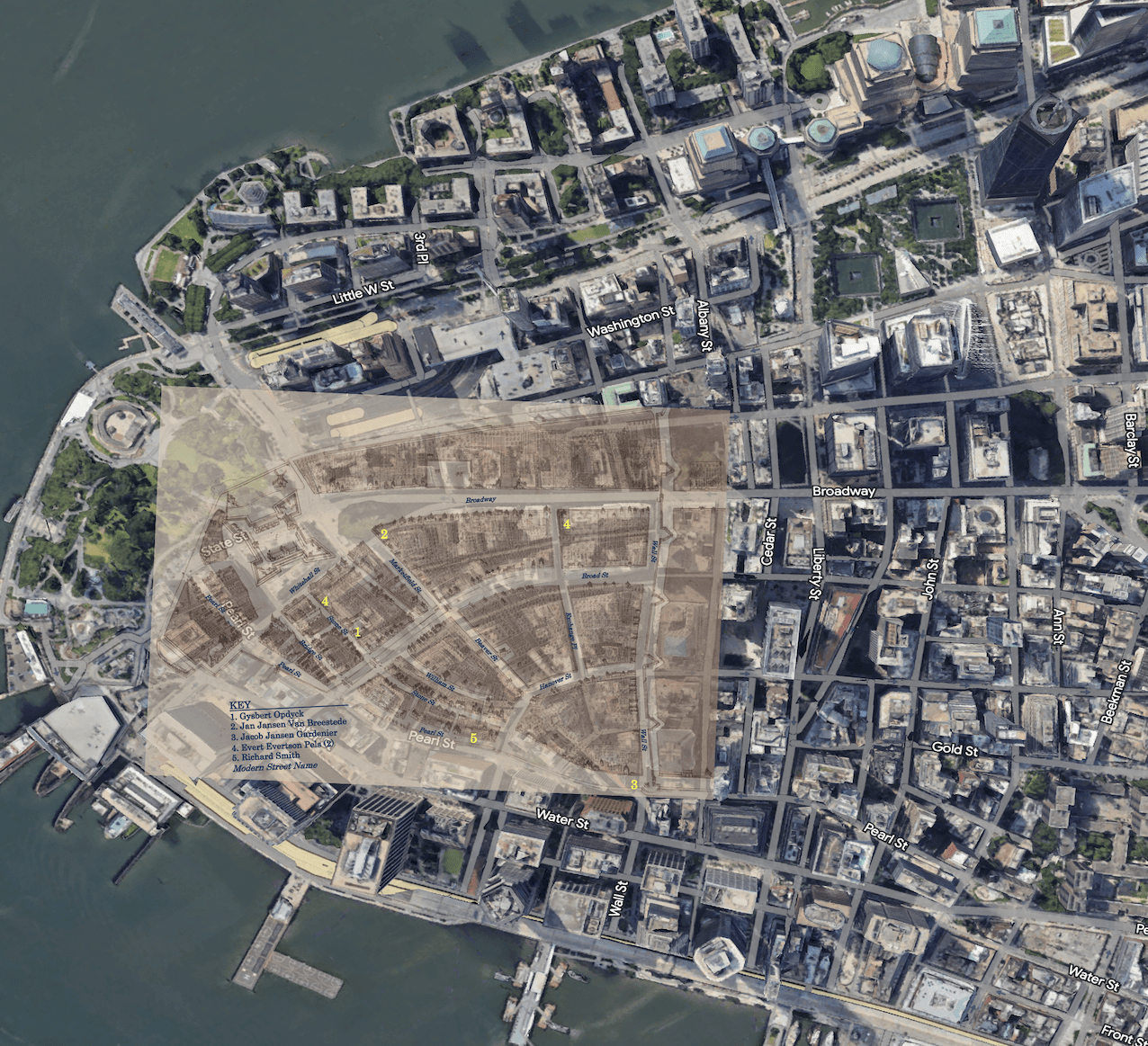

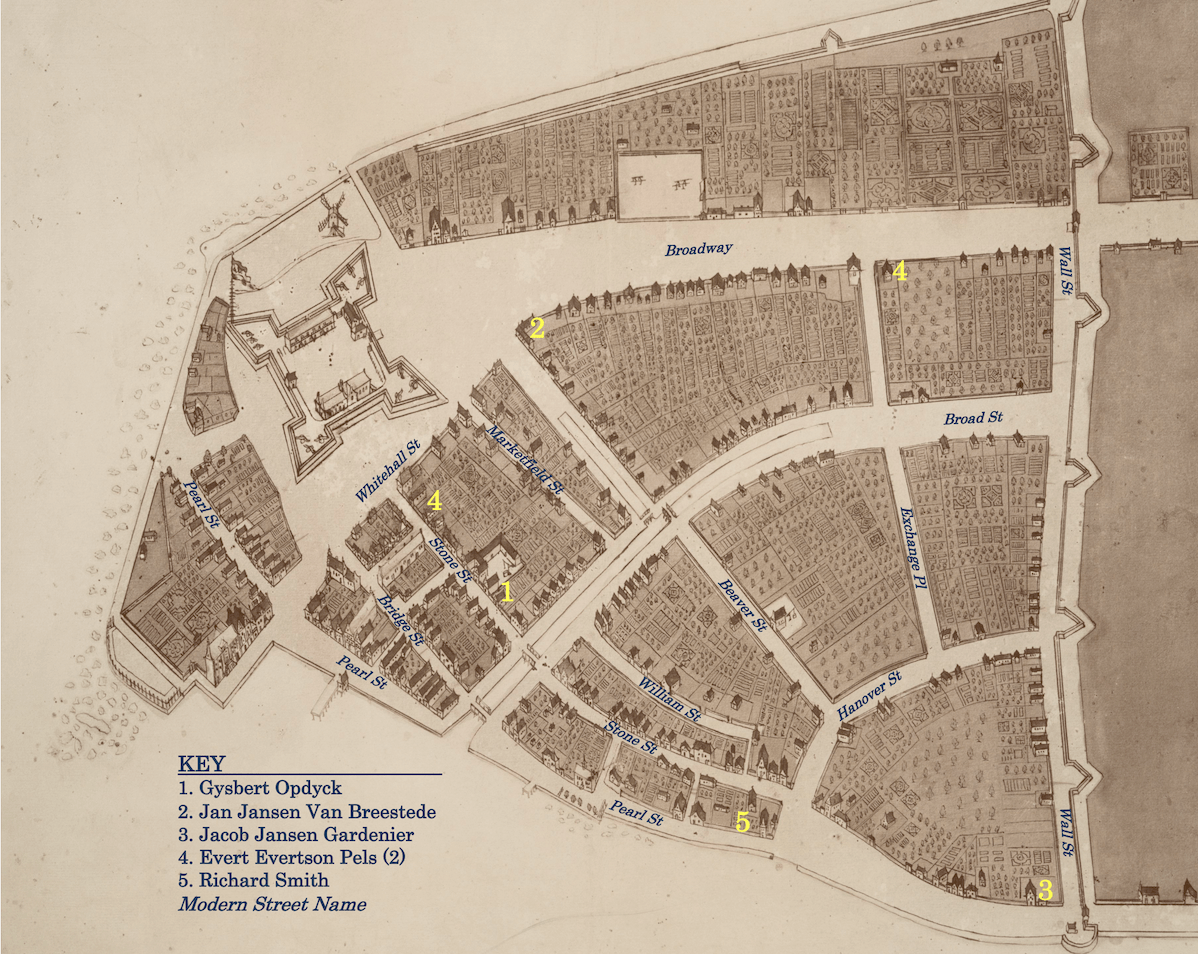

The scale of what was then the island of Manhattan is easy to lose today. Since I have worked in Manhattan for over 30 years, I’m intimately familiar with the old streets. Below, to the original Castello plan, I stretched it slightly and rotated a few degrees clockwise and placed it transparently on top of a Google Earth image. The scale of the landfill is astounding. Pearl Street was the waterfront, and Richard Smith’s house was fronted by a wharf. Jan Jansen van Breestede lived right where the charging bull statue is today. Jacob Jansen Gardenier (“Flodder”) had the waterfront land where Wall, Pearl, and Beaver all come together. Broad Street was a canal. Trinity Place was waterfront along the river. Such a difference of time and place. With rising sea levels, I’d want to live upon the old map.